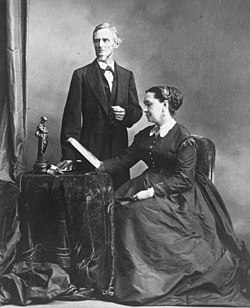

Varina Davis

Born and raised in the Southern United States and educated in Philadelphia, she had family on both sides of the conflict and unconventional views for a woman in her public role.

[2][3] After moving his family from Virginia to Mississippi, James Kempe also bought land in Louisiana, continuing to increase his holdings and productive capacity.

[4] William Howell worked as a planter, merchant, politician, postmaster, cotton broker, banker, and military commissary manager, but never secured long-term financial success.

[citation needed] Varina Howell was sent to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for her education, where she studied at Madame Deborah Grelaud's French School, a prestigious academy for young ladies.

)[citation needed] While at school in Philadelphia, Varina got to know many of her northern Howell relatives; she carried on a lifelong correspondence with some, and called herself a "half-breed" for her connections in both regions.

[8] In her later years, Varina referred fondly to Madame Grelaud and Judge Winchester; she sacrificed to provide the highest quality of education for her two daughters in their turn.

He impresses me as a remarkable kind of man, but of uncertain temper, and has a way of taking for granted that everybody agrees with him when he expresses an opinion, which offends me; yet he is most agreeable and has a peculiarly sweet voice and a winning manner of asserting himself.

The fact is, he is the kind of person I should expect to rescue one from a mad dog at any risk, but to insist upon a stoical indifference to the fright afterward.

[12] The Davises lived in Washington, DC, for most of the next fifteen years before the American Civil War, which gave Varina Howell Davis a broader outlook than many Southerners.

After her husband's return from the war, Varina Davis did not immediately accompany him to Washington when the Mississippi legislature appointed him to fill a Senate seat.

He had unusual visibility for a freshman senator because of his connections as the son-in-law (by his late wife) and former junior officer of President Zachary Taylor.

Varina Davis enjoyed the social life of the capital and quickly established herself as one of the city's most popular (and, in her early 20s, one of the youngest) hostesses and party guests.

The 1904 memoir of her contemporary, Virginia Clay-Clopton, described the lively parties of the Southern families in this period with other Congressional delegations, as well as international representatives of the diplomatic corps.

In 1855, she gave birth to a healthy daughter, Margaret (1855–1909); followed by two sons, Jefferson, Jr., (1857–1878) and Joseph (1859–1864), during her husband's remaining tenure in Washington, D.C.

At the request of the Pierces, the Davises, both individually and as a couple, often served as official hosts at White House functions in place of the President and his wife.

According to diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, in 1860 Mrs. Davis "sadly" told a friend "The South will secede if Lincoln is made president.

Due to her husband's influence, her father William Howell received several low-level appointments in the Confederate bureaucracy which helped support him.

James Dennison and his wife, Betsey, who had served as Varina's maid, used saved back pay of 80 gold dollars to finance their escape.

[citation needed] In spring 1864, five-year-old Joseph Davis died in a fall from the porch at the Presidential mansion in Richmond.

[citation needed] While visiting their daughters enrolled in boarding schools in Europe, Jefferson Davis received a commission as an agent for an English consortium seeking to purchase cotton from the southern United States.

Advised to take a home near the sea for his health, he accepted an invitation from Sarah Anne Ellis Dorsey, a widowed heiress, to visit her summer cottage Beauvoir on the Mississippi Sound in Biloxi.

[citation needed] Sarah Dorsey was determined to help support the former president; she offered to sell him her house for a reasonable price.

Learning she had breast cancer, Dorsey made over her will to leave Jefferson Davis free title to the home, as well as much of the remainder of her financial estate.

In 1891 Varina Davis accepted the Pulitzers' offer to become a full-time columnist and moved to New York City with her daughter Winnie.

[citation needed] Varina Howell Davis was one of numerous influential Southerners who moved to the North for work after the war; they were nicknamed "Confederate carpetbaggers".

[citation needed] She was active socially until poor health in her final years forced her retirement from work and any sort of public life.

Her coffin was taken by train to Richmond, accompanied by the Reverend Nathan A. Seagle, Rector of Saint Stephen's Protestant Episcopal Church, New York City which Davis attended.

She was interred with full honors by Confederate veterans at Hollywood Cemetery and was buried adjacent to the tombs of her husband and their daughter Winnie.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina caused extensive wind and water damage to Beauvoir, which houses the Jefferson Davis Presidential Library.

Varina Howell Davis's diamond and emerald wedding ring, one of the few valuable possessions she was able to retain through years of poverty, was held by the Museum at Beauvoir and lost during the destruction of Hurricane Katrina.