Vault (architecture)

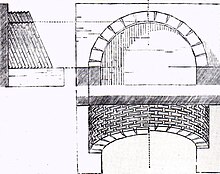

In architecture, a vault (French voûte, from Italian volta) is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof.

The real vault construction with radially joined stones was already known to the Egyptians and Assyrians and was introduced into the building practice of the West by the Etruscans.

However, monumental temple buildings of the pharaonic culture in the Nile Valley did not use vaults, since even the huge portals with widths of more than 7 meters were spanned with cut stone beams.

[citation needed] Dating from c. 6000 BCE, the circular buildings supported beehive shaped corbel domed vaults of unfired mud-bricks and also represent the first evidence for settlements with an upper floor.

[7] The earliest barrel vaults in ancient Egypt are thought to be those in the granaries built by the 19th dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II, the ruins of which are behind the Ramesseum, at Thebes.

to the Sassanians, who in their palaces in Sarvestan and Firouzabad built domes of similar form to those shown in the Nimrud sculptures, the chief difference being that, constructed in rubble stone and cemented with mortar, they still exist, though probably abandoned on the Islamic invasion in the 7th century.

thick); on these and on the trusses transverse rings of brick were built with longitudinal ties at intervals; on the brick layers and embedding the rings and cross ties concrete was thrown in horizontal layers, the haunches being filled in solid, and the surface sloped on either side and covered over with a tile roof of low pitch laid direct on the concrete.

One of the important ingredients of the mortar was a volcanic deposit found near Rome, known as pozzolana, which, when the concrete had set, not only made the concrete as solid as the rock itself, but to a certain extent neutralized the thrust of the vaults, which formed shells equivalent to that of a metal lid; the Romans, however, do not seem to have recognized the value of this pozzolana mixture, for they otherwise provided amply for the counteracting of any thrust which might exist by the erection of cross walls and buttresses.

In the tepidaria of the Thermae and in the basilica of Constantine, in order to bring the thrust well within the walls, the main barrel vault of the hall was brought forward on each side and rested on detached columns, which constituted the principal architectural decoration.

Their construction must at all times have been somewhat difficult, but where the barrel vaulting was carried round over the choir aisle and was intersected (as in St Bartholomew-the-Great in Smithfield, London) by semicones instead of cylinders, it became worse and the groins more complicated.

To meet this, at first the transverse and wall ribs were stilted, or the upper part of their arches was raised, as in the Abbaye-aux-Hommes at Caen, and the Abbey of Lessay, in Normandy.

[16] Besides Cefalù Cathedral, the introduction of the pointed arch rib would seem to have taken place in the choir aisles of the abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, built by the abbot Suger in 1135.

As has been pointed out, the aisles had already in the early Christian churches been covered over with groined vaults, the only advance made in the later developments being the introduction of transverse ribs' dividing the bays into square compartments.

In England sexpartite vaults exist at Canterbury (1175) (set out by William of Sens), Rochester (1200), Lincoln (1215), Durham (east transept), and St.

The tas-de-charge, or solid springer, had two advantages: (1) it enabled the stone courses to run straight through the wall, so as to bond the whole together much better; and (2) it lessened the span of the vault, which then required a centering of smaller dimensions.

[12] The fan vault would seem to have owed its origin to the employment of centerings of one curve for all the ribs, instead of having separate centerings for the transverse, diagonal wall and intermediate ribs; it was facilitated also by the introduction of the four-centred arch, because the lower portion of the arch formed part of the fan, or conoid, and the upper part could be extended at pleasure with a greater radius across the vault.

These ribs were often cut from the same stones as the webs, with the entire vault being treated as a single jointed surface covered in interlocking tracery.

[20] The earliest example is perhaps the east walk of the cloister at Gloucester, with its surface consisting of intricately decorated panels of stonework forming conical structures that rise from the springers of the vault.

[20][21] In later examples, as in King's College Chapel, Cambridge, on account of the great dimensions of the vault, it was found necessary to introduce transverse ribs, which were required to give greater strength.

One of the defects of the fan vault at Gloucester is the appearance it gives of being half sunk in the wall; to remedy this, in the two buildings just quoted, the complete conoid is detached and treated as a pendant.

[19] The vault of the Basilica of Maxentius, completed by Constantine, was the last great work carried out in Rome before its fall, and two centuries pass before the next important development is found in the Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) at Constantinople.

The construction of the pendentives is not known, but it is surmised that to the top of the pendentives they were built in horizontal courses of brick, projecting one over the other, the projecting angles being cut off afterwards and covered with stucco in which the mosaics were embedded; this was the method employed in the erection of the Périgordian domes, to which we shall return; these, however, were of less diameter than those of the Hagia Sophia, being only about 40 to 60 feet (18 m) instead of 107 feet (33 m) The apotheosis of Byzantine architecture, in fact, was reached in Hagia Sophia, for although it formed the model on which all subsequent Byzantine churches were based, so far as their plan was concerned, no domes approaching the former in dimensions were even attempted.

Instead of the spherical spandril of Hagia Sophia, large niches were formed in the angles, as in the Mosque of Damascus, which was built by Byzantine workmen for the Al-Walid I in CE 705; these gave an octagonal base on which the hemispherical dome rested; or again, as in the Sassanian palaces of Sarvestan and Firouzabad of the 4th and 5th century, when a series of concentric arch rings, projecting one in front of the other, were built, giving also an octagonal base; each of these pendentives is known as a squinch.

[15] One good example of the fan vault is that over the staircase leading to the hall of Christ Church, Oxford, where the complete conoid is displayed in its centre carried on a central column.

Thus, in Germany, recognizing that the rib was no longer a necessary constructive feature, they cut it off abruptly, leaving a stump only; in France, on the other hand, they gave still more importance to the rib, by making it of greater depth, piercing it with tracery and hanging pendants from it, and the web became a horizontal stone paving laid on the top of these decorated vertical webs.

This is the characteristic of the great Renaissance work in France and Spain; but it soon gave way to Italian influence, when the construction of vaults reverted to the geometrical surfaces of the Romans, without, however, always that economy in centering to which they had attached so much importance, and more especially in small structures.

In large vaults, where it constituted an important expense, the chief boast of some of the most eminent architects has been that centering was dispensed with, as in the case of the dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, built by Filippo Brunelleschi, and Ferguson cites as an example the great dome of the church at Mousta in Malta, erected in the first half of the 19th century, which was built entirely without centering of any kind.

The reasons for this development are hypothetical, but the fact that the roofed basilica form preceded the era when vaults begin to be made is certainly to be taken into consideration.

The separation between interior and exterior – and between structure and image – was to be developed very purposefully in the Renaissance and beyond, especially once the dome became reinstated in the Western tradition as a key element in church design.