Vedanta

The word Vedanta means 'conclusion of the Vedas', and encompasses the ideas that emerged from, or aligned and reinterpreted, the speculations and enumerations contained in the Upanishads, focusing, with varying emphasis on devotion and knowledge, and liberation.

Vedanta developed into many traditions, all of which give their specific interpretations of a common group of texts called the Prasthānatrayī, translated as 'the three sources': the Upanishads, the Brahma Sutras, and the Bhagavad Gita.

While the monism of Advaita has attracted considerable attention in the West due to the influence of the 14th century Advaitin Vidyaranya and modern Hindus like Swami Vivekananda and Ramana Maharshi, most Vedanta traditions focus on Vaishnava theology.

[14][15] The meaning of Vedanta expanded later to encompass the different philosophical traditions that interpret and explain the Prasthanatrayi in the light of their respective views on the relation between humans and the Divine or Absolute reality.

[12][16] The Upanishads may be regarded as the end of Vedas in different senses:[17] Vedanta is one of the six orthodox (āstika) traditions of textual exegesis and Indian philosophy.

[29] This is explained by Rāmānuja as follows:A theory that rests exclusively on human concepts may at some other time or place be refuted by arguments devised by cleverer people....

Vallabha, in his Shuddhadvaita philosophy, not only accepts the triple ontological essence of the Brahman, but also His manifestation as personal God (Īśvara), as matter, and as individual souls.

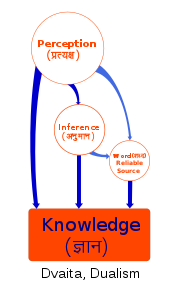

[46] It refers to epistemology in Indian philosophies, and encompasses the study of reliable and valid means by which human beings gain accurate, true knowledge.

[48] Ancient and medieval Indian texts identify six[c] pramanas as correct means of accurate knowledge and truths:[49] The different schools of Vedanta have historically disagreed as to which of the six are epistemologically valid.

In contrast to Badarayana, post-Shankara Advaita Vedantists hold a different view, Vivartavada, which says that the effect, the world, is merely an unreal (vivarta) transformation of its cause, Brahman.

Vinayak Sakaram Ghate of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis of the Brahma Sutra commentaries by Nimbarka, Ramanuja, Vallabha, Shankara and Madhva.

[82] Vishishtadvaita is a qualified non-dualistic school of Vedanta and like Advaita, begins by assuming that all souls can hope for and achieve the state of blissful liberation.

Adherents believe that they can achieve moksha (liberation) by becoming aksharrup (or brahmarup), that is, by attaining qualities similar to Akshar (or Aksharbrahman) and worshipping Purushottam (or Parabrahman; the supreme living entity; God).

[95] Shuddhadvaita (pure non-dualism), propounded by Vallabhacharya (1479–1531 CE), states that the entire universe is real and is subtly Brahman only in the form of Krishna.

[97] Achintya-Bheda-Abheda represents the philosophy of "inconceivable difference in non-difference",[98] in relation to the non-dual reality of Brahman-Atman which it calls (Krishna), svayam bhagavan.

[102][62][l] It is clear that Badarayana, the writer of Brahma Sutras, was not the first person to systematize the teachings of the Upanishads, as he quotes six Vedantic teachers before him – Ashmarathya, Badari, Audulomi, Kashakrtsna, Karsnajini and Atreya.

[102][o] Isaeva suggests they were complete and in current form by 200 CE,[113] while Nakamura states that "the great part of the Sutra must have been in existence much earlier than that" (800 - 500 BCE).

[125] In the Kārikā, Advaita (non-dualism) is established on rational grounds (upapatti) independent of scriptural revelation; its arguments are devoid of all religious, mystical or scholastic elements.

[s] The fact that Shankara, in addition to the Brahma Sutras, the principal Upanishads and the Bhagvad Gita, wrote an independent commentary on the Kārikā proves its importance in Vedāntic literature.

[127][t] A noted contemporary of Shankara was Maṇḍana Miśra, who regarded Mimamsa and Vedanta as forming a single system and advocated their combination known as Karma-jnana-samuchchaya-vada.

[136] Bhakti poets or teachers such as Manavala Mamunigal, Namdev, Ramananda, Surdas, Tulsidas, Eknath, Tyagaraja, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and many others influenced the expansion of Vaishnavism.

[158] Due to the commentarial work of Bhadreshdas Swami, the Akshar-Purushottam teachings were recognized as a distinct school of Vedanta by the Shri Kashi Vidvat Parishad in 2017[67][68] and by members of the 17th World Sanskrit Conference in 2018.

[160] Neo-Vedanta, variously called as "Hindu modernism", "neo-Hinduism", and "neo-Advaita", is a term that denotes some novel interpretations of Hinduism that developed in the 19th century,[161] presumably as a reaction to the colonial British rule.

Western orientalists, in their search for its "essence", attempted to formulate a notion of "Hinduism" based on a single interpretation of Vedanta as a unified body of religious praxis.

133–136) asserts that the neo-Vedantic theory of "overarching tolerance and acceptance" was used by the Hindu reformers, together with the ideas of Universalism and Perennialism, to challenge the polemic dogmatism of Judaeo-Christian-Islamic missionaries against the Hindus.

[171][page needed] Nicholson (2010, p. 2) writes that the attempts at integration which came to be known as neo-Vedanta were evident as early as between the 12th and the 16th century− ... certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the "six systems" (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy.

...It is rather odd that, although the early Indologists' romantic dream of discovering a pure (and probably primitive, according to some) form of Hinduism (or Buddhism as the case may be) now stands discredited in many quarters; concepts like neo-Hinduism are still bandied about as substantial ideas or faultless explanation tools by the Western 'analytic' historians as well as the West-inspired historians of India.According to Nakamura (2004, p. 3), the Vedanta school has had a historic and central influence on Hinduism: The prevalence of Vedanta thought is found not only in philosophical writings but also in various forms of (Hindu) literature, such as the epics, lyric poetry, drama and so forth.

[176]Gavin Flood states, ... the most influential school of theology in India has been Vedanta, exerting enormous influence on all religious traditions and becoming the central ideology of the Hindu renaissance in the nineteenth century.

His works, including those on history of philosophy and Upanishad translations, portrayed Vedanta as the core of Indian thought, shaping 20th century scholarship.

He proposed a six-stage regression model tracing philosophy's decline from monistic idealism to realism and theism, paralleling Indian and Greek traditions.