Venezuelan refugee crisis

[4] From May to August 2023, 390,000 Venezuelans left their country, driven by despair over challenging living conditions, characterized by low wages, rampant inflation, lack of public services, and political repression.

[38] Venezuelan men initially left their wives, children and elderly relatives behind as they fled the country to find work in order to send money back home.

[12] The UNHCR and IOM released data in November 2018 showing that the number of refugees fleeing Venezuela since the Bolivarian revolution began in 1999 had risen to 3 million, around 10 percent of the country's population.

El Universal reported that according to the UCV study Venezuelan Community Abroad: A New Method of Exile, by Tomás Páez, Mercedes Vivas and Juan Rafael Pulido, the Bolivarian diaspora has been caused by the "deterioration of both the economy and the social fabric, rampant crime, uncertainty and lack of hope for a change of leadership in the near future".

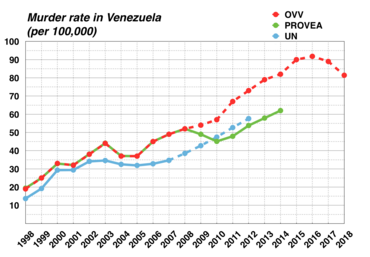

[66] According to Gareth A. Jones and Dennis Rodgers in their book, Youth Violence in Latin America: Gangs and Juvenile Justice in Perspective, the change of regime that came with Chávez's presidency caused political conflict, which was "marked by a further increase in the number and rate of violent deaths".

[81][82][83][84][85] According to a 2018 Gallup analysis, "[g]overnment decisions have led to a domino-effect crisis that continues to worsen, leaving residents unable to afford basic necessities such as food and housing", with Venezuelans "believ[ing] they can find better lives elsewhere".

[89] The economic and political situation in Venezuela led to increasing levels of poverty and scarcity of resources including food and medicine, greatly impacting the health and well-being of Venezuelans.

[73] According to Venezuelan Community Abroad: A New Method of Exile, the Bolivarian government "would rather urge those who disagree with the revolution to leave, instead of pausing to think deeply about the damage this diaspora entails to the country".

[1] The Florida Center for Survivors of Torture reported in 2015 that most of those they assisted since the previous year were Venezuelan migrants, with the organization providing psychiatrists, social workers, interpreters, lawyers and doctors for dozens of individuals and their families.

[15] Iván de la Vega of the Simón Bolívar University (USB) found that 60 to 80 percent of students in Venezuela said that they want to leave the country and not return to 2015 conditions.

[93][94] According to a 2014 report that Iván de la Vega wrote, about 1 million Venezuelans had emigrated during the Chávez presidency but the number of academics was unknown;[95] UCV lost more than 700 of its 4,000 professors between 2011 and 2015.

[1] A Latin America Economic System study reported that the emigration of highly skilled laborers age 25 or older from Venezuela to OECD countries rose by 216 percent between 1990 and 2007.

[118] The Somos Diáspora network, consisting of a website and radio station in Lima, Peru, was launched in May 2018 to provide Venezuelan entertainment, news and migration information to the diaspora.

[146] Between 2015 and 2017, Venezuelan immigration increased by 1,388% in Chile, 1,132% in Colombia, 1,016% in Peru, 922% in Brazil, 344% in Argentina and Ecuador, 268% in Panama, 225% in Uruguay, 104% in Mexico, 38% in Costa Rica, 26% in Spain, and 14% in the United States.

While the offering of humanitarian permits is a positive development, it should not divert attention from a more critical issue: the White House's new strategy to manage Venezuelan migration reaffirms the controversial deportation policy established during Donald Trump's presidency.

Initially invoked during the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, this health rule allows for the immediate deportation of migrants apprehended at the border without processing asylum claims, citing the prevention of COVID-19 spread.

Unable to expel these migrants to Mexico or their countries of origin due to diplomatic tensions, a large percentage remained undeposed, inadvertently incentivizing more individuals from these nations to journey to the border.

[153] Key Events: Latin American countries, such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Panama, are popular destinations for Venezuelan emigrants.

Attracted by better living conditions, many risk the trip by land; Marjorie Campos, a Venezuelan woman who was eight months pregnant, traveled by bus for 11 days across Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile to reach the Argentine city of Cordoba.

[164] Simultaneously, Venezuela's political and economic crisis has amplified the migratory flow to Brazil, bringing added challenges for the roughly 20,000 Yanomami living in Venezuelan territory.

In Lula's words, shared on his social media: "More than a humanitarian crisis, what I witnessed in Roraima was genocide, a premeditated crime against the Yanomami, perpetrated by a government indifferent to the suffering of the Brazilian people.".

[164] Images disseminated by the international press vividly showcase the severity of the situation: Yanomami children with swollen bellies and skin clinging to ribs, revealing the famine and critical health state of the populace.

[164] This scenario underscores the vulnerability of indigenous communities against economic and political interests, as well as the repercussions of Venezuelan migration, underlining the pressing need for measures to protect their rights and way of life.

[170] Beginning in January 2020, the Colombian government announced it would offer work permits to hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans living in Colombia, allowing them to integrate into the formal economy.

According to Catholic Chilean Migration Institute executive secretary Delio Cubides, most Venezuelan immigrants "are accountants, engineers, teachers, the majority of them very well-educated" but accept low-paying jobs so they can meet visa requirements and remain in the country.

Several media outlets and human rights organizations have reported poor conditions, including overcrowding of cells, violence from the guards, and lack of basic hygiene products for Venezuelan migrants in detention.

[194] Venezuelans have historically emigrated, both legally and illegally, to Trinidad and Tobago due to the country's relatively-stable economy, access to United States dollars, and close proximity to eastern Venezuela.

[73] In April 2019, non-governmental organizations Human Rights Watch and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to publish a report and asked the United Nations (UN) to define the situation in Venezuela as a complex humanitarian emergency.

Further, the Church has funded La Soledad, a shelter based in Mexico City that provides refugees access to food, medical assistance, legal advice, and a safe place to rest.

[245][246] The Quito Declaration on Human Mobility and Venezuelan Citizens in the Region was signed in the Ecuadorian capital on September 4, 2018, by the representatives of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

* UN dashed line is projected from missing data.