Venturi effect

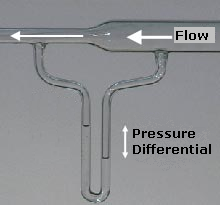

The Venturi effect is the reduction in fluid pressure that results when a moving fluid speeds up as it flows from one section of a pipe to a smaller section.

The effect has various engineering applications, as the reduction in pressure inside the constriction can be used both for measuring the fluid flow and for moving other fluids (e.g. in a vacuum ejector).

In inviscid fluid dynamics, an incompressible fluid's velocity must increase as it passes through a constriction in accord with the principle of mass continuity, while its static pressure must decrease in accord with the principle of conservation of mechanical energy (Bernoulli's principle) or according to the Euler equations.

Thus, any gain in kinetic energy a fluid may attain by its increased velocity through a constriction is balanced by a drop in pressure because of its loss in potential energy.

By measuring the pressure difference without needing to measure the actual pressures at the two points, the flow rate can be determined, as in various flow measurement devices such as Venturi meters, Venturi nozzles and orifice plates.

Referring to the adjacent diagram, using Bernoulli's equation in the special case of steady, incompressible, inviscid flows (such as the flow of water or other liquid, or low-speed flow of gas) along a streamline, the theoretical static pressure drop at the constriction is given by

is the (faster) fluid velocity where the pipe is narrower (as seen in the figure).

The static pressure at each position is measured using a small tube either outside and ending at the wall or into the pipe where the small tube is perpendicular to the flow direction.

When a fluid system is in a state of choked flow, a further decrease in the downstream pressure environment will not lead to an increase in velocity, unless the fluid is compressed.

This is the principle of operation of a de Laval nozzle.

The Bernoulli equation is invertible, and pressure should rise when a fluid slows down.

Nevertheless, if there is an expansion of the tube section, turbulence will appear, and the theorem will not hold.

Generally in Venturi tubes, the pressure in the entrance is compared to the pressure in the middle section and the output section is never compared with them.

Fluid flows through a length of pipe of varying diameter.

To avoid undue aerodynamic drag, a Venturi tube typically has an entry cone of 30 degrees and an exit cone of 5 degrees.

[1] Venturi tubes are often used in processes where permanent pressure loss is not tolerable and where maximum accuracy is needed in case of highly viscous liquids.

[citation needed] Venturi tubes are more expensive to construct than simple orifice plates, and both function on the same basic principle.

However, for any given differential pressure, orifice plates cause significantly more permanent energy loss.

[2] Both Venturi tubes and orifice plates are used in industrial applications and in scientific laboratories for measuring the flow rate of liquids.

If a pump forces the liquid through a tube connected to a system consisting of a Venturi to increase the liquid speed (the diameter decreases), a short piece of tube with a small hole in it, and last a Venturi that decreases speed (so the pipe gets wider again), the gas will be sucked in through the small hole because of changes in pressure.

See aspirator and pressure head for discussion of this type of siphon.

This principle can be used in metrology for gauges calibrated for differential pressures.

The first large-scale Venturi meters to measure liquid flows were developed by Clemens Herschel who used them to measure small and large flows of water and wastewater beginning at the end of the 19th century.

[3] While working for the Holyoke Water Power Company, Herschel would develop the means for measuring these flows to determine the water power consumption of different mills on the Holyoke Canal System, first beginning development of the device in 1886, two years later he would describe his invention of the Venturi meter to William Unwin in a letter dated June 5, 1888.

[4] Fundamentally, pressure-based meters measure kinetic energy density.

Bernoulli's equation (used above) relates this to mass density and volumetric flow:

However, measurements outside the design point must compensate for the effects of temperature, pressure, and molar mass on density and concentration.

Substituting these two relations into the pressure-flow equations above yields the fully compensated flows:

Q, m, or n are easily isolated by dividing and taking the square root.

Note that pressure-, temperature-, and mass-compensation is required for every flow, regardless of the end units or dimensions.