Vestibular system

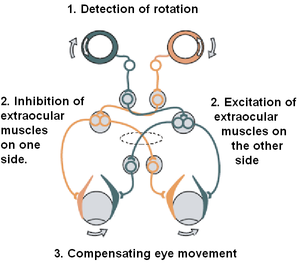

The vestibular system sends signals primarily to the neural structures that control eye movement; these provide the anatomical basis of the vestibulo-ocular reflex, which is required for clear vision.

Each of these three pairs works in a push-pull fashion: when one canal is stimulated, its corresponding partner on the other side is inhibited, and vice versa.

The VOR reflex does not depend on visual input and works even in total darkness or when the eyes are closed.

Signals from the vestibular system also project to the cerebellum (where they are used to keep the VOR effective, a task usually referred to as learning or adaptation) and to different areas in the cortex.

The vestibular nuclei on either side of the brainstem exchange signals regarding movement and body position.

Each hair cell of a macula has forty to seventy stereocilia and one true cilium called a kinocilium.

These otoconia add to the weight and inertia of the membrane and enhance the sense of gravity and motion.

With the head erect, the otolithic membrane bears directly down on the hair cells and stimulation is minimal.

However, when the head is tilted, the otolithic membrane sags and bends the stereocilia, stimulating the hair cells.

[6] Essentially, these otolithic organs sense how quickly you are accelerating forward or backward, left or right, or up or down.

Humans can sense head tilting and linear acceleration even in dark environments because of the orientation of two groups of hair cell bundles on either side of the striola.

[8] Sensory information is then sent to the brain, which can respond with appropriate corrective actions to the nervous and muscular systems to ensure that balance and awareness are maintained.

[10] Although the vestibular system is a very fast sense used to generate reflexes, including the righting reflex, to maintain perceptual and postural stability, compared to the other senses of vision, touch and audition, vestibular input is perceived with delay.

[11][12]Diseases of the vestibular system can take different forms and usually induce vertigo[citation needed][13] and instability or loss of balance, often accompanied by nausea.

In certain head positions, these particles shift and create a fluid wave which displaces the cupula of the canal affected, which leads to dizziness, vertigo and nystagmus.

A similar condition to BPPV may occur in dogs and other mammals, but the term vertigo cannot be applied because it refers to subjective perception.

This condition is very rare in young dogs but fairly common in geriatric animals, and may affect cats of any age.

[14] Vestibular dysfunction has also been found to correlate with cognitive and emotional disorders, including depersonalization and derealization.

Additionally, the vestibular systems of lampreys and hagfish differ from those found in other vertebrates in that the otolithic organs of lampreys and hagfish are not segmented like the utricle and saccule found in humans, but rather form one continuous structure referred to as the macula communis.

[17][18] Behavioral evidence suggests that this system is responsible for stabilizing the body during walking and standing.