19th-century London

In the 1880s and 1890s tens of thousands of Jews escaping persecution and poverty in Eastern Europe came to London and settled largely in the East End around Houndsditch, Whitechapel, Aldgate, and parts of Spitalfields.

[20] London's first Chinatown, as this area of Limehouse became known, was depicted in novels like Charles Dickens' The Mystery of Edwin Drood and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray as a sinister quarter of crime and opium dens.

[24] Anxious West Indian traders combined to fund a private police force to patrol Thames shipping in 1798, under the direction of magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and Master Mariner John Harriott.

Easy access to coal shipments from northeast England via the Port of London meant that a profusion of industries proliferated along the Regent's Canal, especially gasworks, and later electricity plants.

[36] Shipping in the Port of London supported a vast army of transport and warehouse workers, who characteristically attended the "call-on" each morning at the entrances to the docks to be assigned work for the day.

[40] The largest and most famous ship of its day, the SS Great Eastern, a collaboration between John Scott Russell and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was constructed at the Millwall Iron Works and launched in 1858.

The city's strengths in banking, stock brokerage, and shipping insurance made it the natural channel for the huge rise in capital investment which occurred after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

[48] The 1862 Bradshaw's Guide to London listed 83 banks, 336 stockbroking firms, 37 currency brokers, 248 ship and insurance brokerages, and 1500 different merchants in the city, selling wares of every conceivable variety.

[50] The result of the shift to financial services in the city was that, even while its residential population was ebbing in favor of the suburbs (there was a net loss of 100,000 people between 1840 and 1900),[51] it retained its historical role as the center of English commerce.

too often – intoxicating drink; the prison, where the victims of a vitiated condition of society expiate the crimes to which they have been drive by starvation and despair; and the workhouse, to which the destitute, the aged, and the friendless hasten to lay down their aching heads – and die!

[61] Mass demolition of slums like St. Giles was the usual method of removing problematic pockets of the city; for the most part this just displaced existing residents because the new dwellings built by private developers were often far too expensive for the previous inhabitants to afford.

[63][64] The Metropolitan Board of Works (the dominant authority before the LCC), was empowered to undertake clearances and to enforce overcrowding and other such standards on landlords by a stream of legislation including the Labouring Classes Dwelling Houses Acts of 1866 and 1867.

[67] The Cheap Trains Act 1883, while it enabled many working class Londoners to move away from the inner city, also accentuated[clarification needed] the poverty in areas like the East End, where the most destitute were left behind.

[56] The 1888 Whitechapel murders perpetrated by Jack the Ripper brought international attention to the squalor and criminality of the East End, while penny dreadfuls and a slew of sensational novels like George Gissing's The Nether World and the works of Charles Dickens painted grim pictures of London's deprived areas for middle and upper class readers.

Booth painstakingly charted levels of deprivation throughout the city, painting a bleak but also sympathetic picture of the wide variety of conditions experienced by London's poor.

[76] This changed with the creation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board in 1867, which embarked on the building of five planned smallpox and fever hospitals in Stockwell, Deptford, Hampstead, Fulham and Homerton to serve the different regions of London.

[115] The embankments protected low-lying areas along the Thames from flooding, provided a more attractive prospect of the river compared to the mudflats and boatyards which abounded previously, and created prime reclaimed land for development.

[123][122] Old London Bridge, whose 20 piers dated back to the 13th century, so impeded the flow of the river that it formed dangerous rapids for boats, and its narrow width of 26 ft could not accommodate modern traffic levels.

[138] In November and December 1848, two competing inventors (M. Le Mott and William Staite) gave demonstrations of their respective electric lamps to astonished crowds at the National Gallery, atop the Duke of York Column, and aboard a train departing from Paddington station.

[150] Montagu House was demolished and the quadrangular current building, with its imposing Greek Revival façade designed by Sir Robert Smirke, rose gradually through 1857, with the East Wing the first to be completed in 1828.

[152][151] The great complex of museums at South Kensington began with the purchase of a vast tract of land (known as Albertopolis) at the instigation of the Prince Consort and the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851.

Song and Supper Rooms of the 1830s and 40s offered patrons, for a surcharge, the opportunity to dine and drink while enjoying live musical acts of a higher caliber than the "Free and Easies".

The combination of cesspools and the raw sewage pumped into the city's main source of drinking water led to repeated outbreaks of cholera in 1832, 1849, 1854, and 1866[176] and culminated in The Great Stink of 1858.

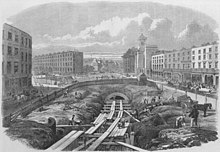

In one of the largest civil engineering projects of the 19th century, he oversaw construction of over 1300 miles or 2100 km of tunnels and pipes under London to take away sewage and provide clean drinking water.

The social reformer Edwin Chadwick condemned the methods of waste removal in British cities, including London, in his 1842 Report on The Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain.

Chadwick attributed the spread of disease to this filth, advocating improved water supplies and drains, and criticising the inefficient system of labourers and street sweepers then employed to maintain cleanliness.

These authorities were more comprehensive than their predecessors, equipped with teams of medical officers and health inspectors who ensured food safety standards were met and actively prevented outbreaks of disease.

Sulphur dioxide and soot emitted from chimneys mixed with the natural vapour of the Thames Valley to form a layer of greasy, acrid mist that shrouded the city up to 240 feet (75 metres) above street level.

Not only does a strange and worse than Cimmerian darkness hide familiar landmarks from the sight, but the taste and sense of smell are offended by an unhallowed compound of flavours, and all things become greasy and clammy to the touch.

[201] Porous brick and stone were quickly blackened with soot, an effect worsened during bad fogs and damp weather, creating a "uniform dinginess" among London's buildings.