Videotex

From the late 1970s to early 2010s, it was used to deliver information (usually pages of text) to a user in computer-like format, typically to be displayed on a television or a dumb terminal.

[1] In a strict definition, videotex is any system that provides interactive content and displays it on a video monitor such as a television, typically using modems to send data in both directions.

Antiope had similar capabilities to the UK system for displaying alphanumeric text and chunky "mosaic" character-based block graphics.

This gave Antiope slightly more flexibility in the use of colours in mosaic block graphics, and in presenting the accents and diacritics of the French language.

In August 1978, the Canadian Department of Communications publicly launched it as Telidon, a "second generation" videotex/teletext service, and committed to a four-year development plan to encourage rollout.

Instead, development focussed on methods to send pages to user terminals pre-rendered, using coding strategies similar to facsimile machines.

This led to a videotex system called Captain ("Character and Pattern Telephone Access Information Network"), created by NTT in 1978, which went into full trials from 1979 to 1981.

NHK developed an experimental teletext system along similar lines, called CIBS ("Character Information Broadcasting Station").

[7][8] This was closely based on the Canadian Telidon system, but added to it some further graphics primitives and a syntax for defining macros, algorithms to define cleaner pixel spacing for the (arbitrarily sizeable) text, and also dynamically redefinable characters and a mosaic block graphic character set, so that it could reproduce content from the French Antiope.

After some further revisions this was adopted in 1983 as ANSI standard X3.110, more commonly called NAPLPS, the North American Presentation Layer Protocol Syntax.

This may have been due primarily to the relatively low penetration of suitable hardware in British homes, requiring the user to pay for the terminal (today referred to as a set-top box), a monthly charge for the service, and phone bills on top of that (unlike the US, local calls were paid for in most of Europe at that time).

Using a prototype domestic television equipped with the Prestel chip set, Michael Aldrich of Redifon Computers Ltd demonstrated a real-time transaction processing in 1979; the idea is currently referred to as online shopping.

[18] He wrote a book about his ideas and systems which among other topics explored a future of online shopping and remote working that has proven to be prophetic.

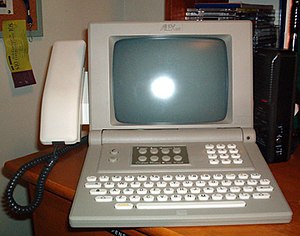

The operating system was CP/M or a proprietary variant CP*, and the unit was supplied with a suite of applications, consisting of a word processor, spreadsheet, database and a semi-compiled basic programming language.

The display supplied with the unit (both the Teleputer 1 and 3) was a modified Rediffusion 14 inch portable colour television, with the tuner circuitry removed and being driven by a RGB input.

The proposed Teleputer 4 & 5 were planned to have a laser disk attached and would allow the units to control video output on a separate screen.

[20] In Canada, the Department of Communications started a lengthy development program in the late 1970s that led to a graphical "second generation" service known as Telidon.

Telidon was able to deliver service using the vertical blanking interval of a TV signal or completely by telephone using a Bell 202 style (split baud rate 150/1200[citation needed]) modem.

The use of the 202 model modem, rather than one compatible with the existing DATAPAC dial-up points such as the Bell 212, created severe limitations, as it made use of the nationwide X.25 packet network essentially out-of-bounds for Telidon-based services.

In an attempt to capitalize on the European experience, a number of US-based media firms started their own videotex systems in the early 1980s.

Furthermore, most of the same information was available in easy-to-use TV format on the air, or in general reference books at the local library, and didn't tie up a landline.

[22] These included: A joint venture of AT&T-CBS completed a moderately successful trial of videotex use in the homes of Ridgewood, New Jersey, leveraging technology developed at Bell Labs.

Because of its relatively late debut, Prodigy was able to skip the intermediate step of persuading American consumers to attach proprietary boxes to their televisions; it was among the earliest proponents of computer-based videotex.

Goldman Sachs, for one, adopted and developed an internal fixed income information distribution and bond sales system based on DEC VTX.

The largest private networks were Travelnet which was an information and booking-system for the travel industry and RDWNet, which was set up for the automobile trade to register the outcome of MOT tests to the agency that officially issued the test-report.

Despite being cutting edge for its time, the system failed to capture a large market and was ultimately withdrawn due to lack of commercial interest.

Online fees were very high, and the useful services such as home banking, restaurant reservations, and news feeds, that Bell Canada advertised did not materialise; within a very short time the majority of content on Alex was of poor quality or very expensive chat lines.

While some people consider videotex to be the precursor of the Internet, the two technologies evolved separately and reflect fundamentally different assumptions about how to computerize communications.

The Internet in its mature form (after 1990) is highly decentralized in that it is essentially a federation of thousands of service providers whose mutual cooperation makes everything run, more or less.

In contrast, videotex was always highly centralized (except in the French Minitel service, also including thousands of information providers running their own servers connected to the packet switched network "TRANSPAC").