Vietnamese cash

The Vietnamese cash (chữ Hán: 文錢 văn tiền; chữ Nôm: 銅錢 đồng tiền; French: sapèque),[a][b] also called the sapek or sapèque,[c] is a cast round coin with a square hole that was an official currency of Vietnam from the Đinh dynasty in 970 until the Nguyễn dynasty in 1945, and remained in circulation in North Vietnam until 1948.

During the Bắc thuộc a number of Chinese currencies circulated in Vietnam, during this period precious metals like gold and silver were also used in commercial transactions but it wasn't until Vietnamese independence that the first natively produced cash coins would appear.

[19] Generally cast coins produced by the Vietnamese from the reign of Lý Thái Tông and onwards were of diminutive quality compared to the Chinese variants.

[21] They were often produced with inferior metallic compositions and made to be thinner and lighter than the Chinese wén due to a severe lack of copper that existed during the Lý dynasty.

[26] Despite these harsh laws, very few people actually preferred paper money and coins remained widespread in circulation, forcing the Hồ dynasty to retract their policies.

[32][33] After Lê Thái Tổ came to power in 1428 by ousting out the Ming dynasty ending the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, the Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư reports that in 1429 it was proposed to reintroduce paper money, but this idea was rejected.

This trade lead to a surplus of copper in the territory of the Nguyễn lords, allowing them to use the metal (which at the time was scarce in the north) for more practical applications such as nails and door hinges.

At the turn of the 18th century Lê Dụ Tông opened a number of copper mines and renewed the production of high quality coinage.

[36] During the Vĩnh Thịnh (永盛, 1706–1719) period of Lê Dụ Tông the first large-format cash coins were issued; they had a diameter of 50.5 mm and a weight of 33.13 grams.

Later to fulfill this need, the Lê legalised the previously detrimental workshops that were minting inferior coins in 1760 in order to meet the market's high demand for coinage; this backfired as the people found the huge variety in quality and quantity confusing.

[46] According to the Đại Nam thực lục tiền biên while fighting the Tây Sơn dynasty, the Thế tổ Cao Hoàng đế issued cash coins with the inscription Gia Hưng Thông Bảo (嘉興通寶) in 1796.

[50] He officially appointed the Bảo tuyền cục to be in charge of minting cash coins at Tây Long gate outside the city of Huế.

[48] In the year Gia Long 13 (1814) another 6 phân zinc cash coin was produced at the Bảo tuyền cục Bắc Thành and ordered them to imitate the minting techniques of the Qing.

[48] According to a document from the year Gia Long 16 (1817) the government of the Nguyễn dynasty ordered for the destruction of all "fake cash coins" from circulation explaining that the prior currency situation was chaotic.

[51] The Tiền cấm included the following three categories:[51] According to the Đại Nam Thực lục chính biên, there were several different types of Gia Long Thông Bảo cash coins cast.

"[48][e] In 1849 the Tự Đức Emperor was forced to legalise the private production of zinc cash coins as too many illegal mints kept being established throughout both Đại Nam and China.

[57][58] In 1882, at the time when Eduardo Toda y Güell's Annam and its minor currency was published, only two government mints remained in operation: one in Hanoi, and one in Huế.

[59] Likewise, Chinese customers in the American state of California would have been similarly discriminating quickly ending the demand for zinc Vietnamese cash coins outside of Vietnam.

Despite the later introduction of the French Indochinese piastre, zinc and copper-alloy cash coins would continue to circulate among the Vietnamese populace throughout the country as the primary form of coinage, as the majority of the population lived in extreme poverty until 1945 (and 1948 in some areas).

[64][61] During the Kiến Phúc period (2 December 1883 – 31 July 1884), the regent Nguyễn Văn Tường accepted bribes from Qing Chinese merchants to allow them to bring their tiền sềnh (錢浧, "extraordinary money") depicting the reign era of the Tự Đức Emperor into the country.

[66][67] Roman Catholic missionaries active in Đại Nam took advantage of bad condition of this new money to propagate the idea that it was a sign that the Nguyễn dynasty was in decline.

[66] However, these earlier low quality money was still heavier and more valuable than the nearly worthless tiền sềnh brought into the country by merchants from the Qing dynasty by the end of the 19th century.

[68] Because the exchange values between the native cash coins and silver piastres were confusing, the local Vietnamese people were often cheated by the money changers during this period.

[72] The ordonnance stated that the people of Đại Nam are "warned that cash coins are for their daily life and serve as an article of their very first necessity" and that "there is no worse malaise than the scarcity of cash coins", while emphasising that the production costs of the currency is higher than their nominal and market value and that their continued production constitutes a heavy burden both for the French Indochinese and Nguyễn dynasty governments, but that the government prefers to bear this burden than let the people suffer from the negative consequences of their scarcity.

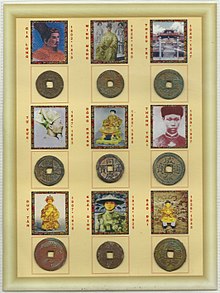

In general, the coins bear the era name(s) of the monarch (Niên hiệu/年號) but may also be inscribed with mint marks, denominations, miscellaneous characters, and decorations.

Gold text Indicates that this is a fake or fantasy referenced by Eduardo Toda y Güell in his Annam and its Minor Currency (pdf), the possible existence of these cash coins have not been verified by any later works.

Since Edouard Toda made his list in 1882, several of the coins that he had described as "originating from the Quảng Nam province" have been ascribed to the Nguyễn lords that the numismatists of his time could not identify.

[144] The Nguyễn dynasty produced a large number of both gold and silver medals which had inscriptions and allegories relating to the Five Precious Things (五寶, ngũ bảo).

The reason these charms are cast on this particular event is because sixty years symbolise a complete cycle of the ten heavenly stems and the twelve earthly branches.

[147] These decorations generally took the shape of silver or gold cash coins as well as other coinages issued by the Nguyễn dynasty, but would often have more elaborate designs and (often) different inscriptions.