French Indochina

Around this time, Vietnam had only just begun its "Southward"—"Nam Tiến", the occupation of the Mekong Delta, a territory being part of the Khmer Empire and to a lesser extent, the kingdom of Champa which they had defeated in 1471.

For its part, the Nguyễn dynasty increasingly saw Catholic missionaries as a political threat; courtesans, for example, an influential faction in the dynastic system, feared for their status in a society influenced by an insistence on monogamy.

De Genouilly was criticised for his actions and was replaced by Admiral Page in November 1859 with instructions to obtain a treaty protecting the Catholic faith in Vietnam while refraining from making territorial gains.

[clarification needed] This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia.

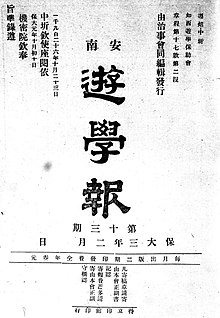

[33] Prince Cường Để hoped that by financing hundreds of young ambitious Vietnamese people to go get educated in Japan that this would contribute to the liberation of his country from French domination.

[33] Using diplomatic pressure the French persuaded the Japanese to banish the Duy Tân Hội in 1909 from its shores causing them to seek refuge in Qing China, here they would join the ranks of Sun Yat-Sen's Tongmenghui.

[33] However, beside some liberal reforms, the French administration actually increased economic exploitation and ruthless repression of nationalist movements which rapidly resulted in a disappointment of the promises made by Sarraut.

This exceptional human mobility offered the French Indochinese, mostly Vietnamese, the unique opportunity of directly access to social life and political debates that were occurring in contemporary France and this resulted in their aspirations to become "masters of their own destiny" to increase.

[62][33] French Indochinese battalions were also used in various logistics functions such as serving as drivers to transport soldiers to the front lines, stretcher bearers (brancardiers), or road crews.

[33] The Great War presented a number of opportunities for the indigenous French Indochinese people serving in the West that didn't exist before, notably for some individuals to obtain levels of education that were simply unattainable at home by acquiring more advanced technical and professional skills.

[67][33] Only a handful of Vietnamese landlords, moneylenders, and middlemen benefitted from the new economic opportunities that arose during this period as the colonial economy of exportation was designed to enrich the French at the expense of the indigenous population.

Among these newspapers was La Tribune indigène (The Indigenous Forum) launched in 1917 by the agronomist Bùi Quang Chiêu working together with the lawyer Dương Văn Giáo and journalist Nguyễn Phan Long.

[33] From 1914 to 1917 members of the Tai Lue people led by Prince Phra Ong Kham (Chao Fa) of Muang Sing organised a long anti-French campaign, Hmong independence movements in Laos also challenged French rule in the country.

[33] Clemenceau also wanted Japan to help by intervening in Siberia to fight the Bolshevik forces during the Russian Civil War to prevent the loss of the many French-Russian loans, which were important for the French post-war economy.

[73] In April 1916 the administrator of civil services at the Political Affairs Bureau in Hanoi launched two voluminous reports that went into great detail about the parallel histories of what he referred to as the "Annamese Revolutionary Party" (how he called the Duy Tân Hội) and of the secret societies of French Cochinchina.

[33] The Sûreté générale indochinoise would be used as the paramount tool to gather intelligence of subversive elements within French Indochinese society and to conduct large-scale union-wide registration by the colonial police forces of suspects and convicts.

[35] The Political Affairs Bureau assembled a umber of Vietnamese elites belonging to the indigenous intelligentsia through the French School of the Far East to aid in the pro-French propaganda effort.

[80][58] Both legal and illegal immigrants entered France from French Indochina working various types of jobs, such as sailors, photographers, cooks, restaurant and shop owners and manual labourers.

[33] Regarding the internal security of the French apparatus in the Far East Sarraut stated "I have always estimated that Indochina must be protected against the effects of a revolutionary propaganda that I have never underestimated, by carrying out a double action, one political, the other repressive.

[93] In April of that year the Vietnamese Communists and their Trotskyist left opposition ran a common slate for the municipal elections with both their respective leaders Nguyễn Văn Tạo and Tạ Thu Thâu winning seats.

[96] Brévié set the election results aside and wrote to Colonial Minister Georges Mandel: "the Trotskyists under the leadership of Ta Thu Thau, want to take advantage of a possible war in order to win total liberation."

[102][103] On 17 August 1970, the North Vietnamese National Assembly Chairman Truong Chinh reprinted an article in Vietnamese in Nhan Dan, published in Hanoi titled "Policy of the Japanese Pirates Towards Our People" which was a reprint of his original article written in August 1945 in No 3 of the "Communist Magazine" (Tap Chi Cong San) with the same title, describing Japanese atrocities like looting, slaughter and rape against the people of north Vietnam in 1945.

He denounced the Japanese claims to have liberated Vietnam from France with the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere announced by Tojo and mentioned how the Japanese looted shrines, temples, eggs, vegetables, straw, rice, chickens, hogs and cattle for their horses and soldiers and built military stations and airstrips after stealing land and taking boats, vehicles, homes and destroying cotton fields and vegetable fields for peanut and jute cultivation in Annam and Tonkin.

In Thai Nguyen province, Vo Nhai, a Vietnamese boat builder was thrown in a river and had his stomach stabbed by the Japanese under suspicion of helping Viet Minh guerillas.

[134] 2 million is often cited as the death toll, but Japanese academic Futuna Motoo disputes the figure as repeating Ho Chi Minh's assertion in the Declaration of Independence of Vietnam on 2 September 1945.

"[139] After the close of hostilities in WWII, 200,000 Chinese troops under General Lu Han sent by Chiang Kai-shek entered French Indochina north of the 16th parallel to accept the surrender of Japanese occupying forces, and remained there until 1946.

[3] In 1949, in order to provide a political alternative to Ho Chi Minh, the French favoured the creation of a unified State of Vietnam, and former Emperor Bảo Đại was put back in power.

Võ Nguyên Giáp, however, used efficient and novel tactics of direct fire artillery, convoy ambushes and massed anti-aircraft guns to impede land and air supply deliveries together with a strategy based on recruiting a sizable regular army facilitated by wide popular support, a guerrilla warfare doctrine and instruction developed in China, and the use of simple and reliable war material provided by the Soviet Union.

[166] In 1954 the French defeat at Điện Biên Phủ renewed the United States interest in intervening, including some senators who called out for large scale bombing campaigns, potentially even nuclear weapons.

[190] The heaviest concentration of French-era buildings are in Hanoi, Đà Lạt, Haiphong, Ho Chi Minh City, Huế, and various places in Cambodia and Laos such as Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Battambang, Kampot, and Kep.

![Thống-Chế đã nói – Đại-Pháp khắng khít với thái bình, như dân quê với đất ruộng [Thống-Chế said: Dai-France clings to peace, like peasants with lands]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Th%E1%BB%91ng-Ch%E1%BA%BF_%C4%91%C3%A3_n%C3%B3i_-_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i-Ph%C3%A1p_kh%E1%BA%AFng_kh%C3%ADt_v%E1%BB%9Bi_th%C3%A1i_b%C3%ACnh%2C_nh%C6%B0_d%C3%A2n_qu%C3%AA_v%E1%BB%9Bi_%C4%91%E1%BA%A5t_ru%E1%BB%99ng.jpg/170px-Th%E1%BB%91ng-Ch%E1%BA%BF_%C4%91%C3%A3_n%C3%B3i_-_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i-Ph%C3%A1p_kh%E1%BA%AFng_kh%C3%ADt_v%E1%BB%9Bi_th%C3%A1i_b%C3%ACnh%2C_nh%C6%B0_d%C3%A2n_qu%C3%AA_v%E1%BB%9Bi_%C4%91%E1%BA%A5t_ru%E1%BB%99ng.jpg)

- Panorama of Lac-Kaï

- Yun-nan , in the quay of Hanoi

- Flooded street of Hanoi

- Landing stage of Hanoi