Glass transition

Hard plastics like polystyrene and poly(methyl methacrylate) are used well below their glass transition temperatures, i.e., when they are in their glassy state.

Other materials, such as many polymers, lack a well defined crystalline state and easily form glasses, even upon very slow cooling or compression.

If slower cooling rates are used, the increased time for structural relaxation (or intermolecular rearrangement) to occur may result in a higher density glass product.

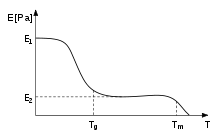

Tg is located at the intersection between the cooling curve (volume versus temperature) for the glassy state and the supercooled liquid.

In contrast, at considerably lower temperatures, the configuration of the glass remains sensibly stable over increasingly extended periods of time.

Time and temperature are interchangeable quantities (to some extent) when dealing with glasses, a fact often expressed in the time–temperature superposition principle.

However, there is a longstanding debate whether there is an underlying second-order phase transition in the hypothetical limit of infinitely long relaxation times.

As a result of the fluctuating input of thermal energy into the liquid matrix, the harmonics of the oscillations are constantly disturbed and temporary cavities ("free volume") are created between the elements, the number and size of which depend on the temperature.

The glass transition temperature Tg0 defined in this way is a fixed material constant of the disordered (non-crystalline) state that is dependent only on the pressure.

As a result of the increasing inertia of the molecular matrix when approaching Tg0, the setting of the thermal equilibrium is successively delayed, so that the usual measuring methods for determining the glass transition temperature in principle deliver Tg values that are too high.

[23] Franz Simon:[24] Glass is a rigid material obtained from freezing-in a supercooled liquid in a narrow temperature range.

Zachariasen:[25] Glass is a topologically disordered network, with short range order equivalent to that in the corresponding crystal.

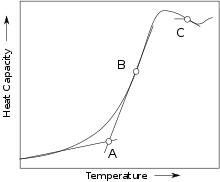

[28] Different operational definitions of the glass transition temperature Tg are in use, and several of them are endorsed as accepted scientific standards.

Nevertheless, all definitions are arbitrary, and all yield different numeric results: at best, values of Tg for a given substance agree within a few kelvins.

is randomly distributed but fixed ("quenched disorder"), then as temperature drops, more and more of these two-level levels are frozen out (meaning that it takes such a long time for a tunneling to occur, that they cannot be experimentally observed).

Any deviations from these standard parameters constitute microstructural differences or variations that represent an approach to an amorphous, vitreous or glassy solid.

For example, addition of elements such as B, Na, K or Ca to a silica glass, which have a valency less than 4, helps in breaking up the network structure, thus reducing the Tg.

From this definition, we can see that the introduction of relatively stiff chemical groups (such as benzene rings) will interfere with the flowing process and hence increase Tg.

Smaller molecules of plasticizer embed themselves between the polymer chains, increasing the spacing and free volume, and allowing them to move past one another even at lower temperatures.

Molecular motion in condensed matter can be represented by a Fourier series whose physical interpretation consists of a superposition of longitudinal and transverse waves of atomic displacement with varying directions and wavelengths.

In other words, simple liquids cannot support an applied force in the form of a shearing stress, and will yield mechanically via macroscopic plastic deformation (or viscous flow).

Furthermore, the fact that a solid deforms locally while retaining its rigidity – while a liquid yields to macroscopic viscous flow in response to the application of an applied shearing force – is accepted by many as the mechanical distinction between the two.

[58][59] The velocities of longitudinal acoustic phonons in condensed matter are directly responsible for the thermal conductivity that levels out temperature differentials between compressed and expanded volume elements.

[62][63] The relationship between these transverse waves and the mechanism of vitrification has been described by several authors who proposed that the onset of correlations between such phonons results in an orientational ordering or "freezing" of local shear stresses in glass-forming liquids, thus yielding the glass transition.

[64] The influence of thermal phonons and their interaction with electronic structure is a topic that was appropriately introduced in a discussion of the resistance of liquid metals.

Such theories of localization have been applied to transport in metallic glasses, where the mean free path of the electrons is very small (on the order of the interatomic spacing).

However, if the model includes the buildup of a charge distribution between all pairs of atoms just like a chemical bond (e.g., silicon, when a band is just filled with electrons) then it should apply to solids.

The electrons will only be sensitive to the short-range order in the glass since they do not get a chance to scatter from atoms spaced at large distances.

It has also been argued that glass formation in metallic systems is related to the "softness" of the interaction potential between unlike atoms.

[74][75] Other authors have suggested that the electronic structure yields its influence on glass formation through the directional properties of bonds.