Vladimir Jochelson

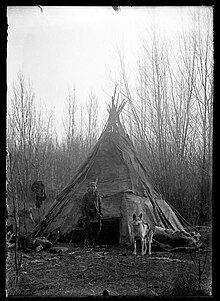

[3][4] In Siberia Jochelson made a special study of the language, manners, and folk-lore of the aboriginal inhabitants, especially that of the Tungus, Yakuts, and the fast-disappearing Yukaghirs.

[3] For the expedition Jochelson spent two and a half years in the distant north, studying primarily the Koryaks, Yukaghir, and Sakha (Yakut), accompanied by his wife Dina Brodskaya, a qualified doctor, who took care of all the anthropometric and medical work, and most of the photography.

[5] The expedition was intended to create a comprehensive record of the peoples being studied, and a very wide range of artefacts and material objects were collected, as well as the final ethnographies and written field-notes of the participants.

He emigrated to New York in 1922 and spent the rest of his life in the United States, where he renewed his association with the American Museum of Natural History, and later with the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C.[4][7] Jochelson contributed extensively to scientific journals in Russian, German and English.

Kozintsev (2020) argues that the historical Southern Siberian Okunevo population, which derives most of its ancestry from Ancient North Eurasians and their closest relatives, possesses this "Americanoid" craniometric phenotype, which represents the variation of the first humans in Siberia.