Craniometry

Today, physical and forensic anthropologists use craniometry to study the evolution of human populations, determining the origin of ancient remains such as the Kennewick Man.

On the other hand, craniometry was also used as evidence against the existence of a "Nordic race" and also by Franz Boas who used the cephalic index to show the influence of environmental factors.

A few studies claim that forensic anthropologists can correctly identify the perceived social race of an individual with rates from 81-99% accuracy depending on the craniometric data, the number of variables used, the populations, and the type of analysis.

[5][6][7] Quite separately, certain artists from the 15th century onward made measurements of heads and skulls with a view to attaining greater accuracy in their representation of those parts of the human frame.

[8] Swedish professor of anatomy Anders Retzius (1796–1860) first used the cephalic index in physical anthropology to classify ancient human remains found in Europe.

He classified brains into three main categories, "dolichocephalic" (from the Ancient Greek kephalê, head, and dolikhos, long and thin), "brachycephalic" (short and broad) and "mesocephalic" (intermediate length and width).

In 1784, Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, who wrote many comparative anatomy memoirs for the Académie française, published the Mémoire sur les différences de la situation du grand trou occipital dans l'homme et dans les animaux (which translates as Memoir on the Different Positions of the Occipital Foramen in Man and Animals).

Camper claimed that antique statues presented an angle of 90°, Europeans of 80°, Black people of 70° and the orangutan of 58°, thus displaying a hierarchic view of mankind, based on a decadent conception of history.

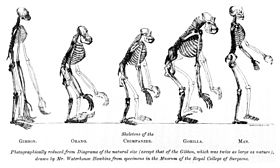

While it is impossible to analyse each contribution, or even record a complete list of the names of the authors, notable researchers who used craniometric methods to compare humans to other animals included T. H. Huxley (1825–1895) of England and Paul Broca.

[12] In particular, Eugène Dubois' (1858–1940) discovery in 1891 in Indonesia of the "Java Man", the first specimen of Homo erectus to be discovered, demonstrated mankind's deep ancestry outside Europe.

Samuel George Morton (1799–1851), one of the inspirers of physical anthropology, collected hundreds of human skulls from all over the world and started trying to find a way to classify them according to some logical criterion.

[13] Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002), an American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist and historian of science, studied these craniometric works in The Mismeasure of Man (1981) and claimed Samuel Morton had fudged data and "overpacked" the skulls with filler in order to justify his preconceived notions on racial differences.

Paul Kretschmer quoted an 1892 discussion with him concerning these criticisms, also citing Aurel von Törok's 1895 work, who basically proclaimed the failure of craniometry.

It was made famous by Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), the founder of anthropological criminology, who claimed to be able to scientifically identify links between the nature of a crime and the personality or physical appearance of the offender.

A few of the 14 identified traits of a criminal included large jaws, forward projection of jaw, low sloping forehead; high cheekbones, flattened or upturned nose; handle-shaped ears; hawk-like noses or fleshy lips; hard shifty eyes; scanty beard or baldness; insensitivity to pain; long arms, and so on.

After being a main influence of US white nationalists, William Ripley's The Races of Europe (1899) was eventually rewritten in 1939, just before World War II, by Harvard physical anthropologist Carleton S.

[citation needed] J. Philippe Rushton, psychologist, head of the Pioneer Fund, an organization founded in 1937 to promote eugenics,[17][18] and author of the controversial work Race, Evolution and Behavior (1995), reanalyzed Gould's retabulation in 1989, and argued that Samuel Morton, in his 1839 book Crania Americana, had shown a pattern of decreasing brain size proceeding from East Asians to Europeans to Africans.

In his 1995 book Race, Evolution, and Behavior, Rushton alleged an average endocranial volume of 1,364 cm3 for East Asians, 1,347 for white caucasians and 1,268 for black Africans.

However, in the same article Beals explicitly warns against using the findings as indicative of racial traits, "If one merely lists such means by geographical region or race, causes of similarity by genogroup and ecotype are hopelessly confounded".

[19] Rushton's findings have also been criticized for questionable methodology, such as lumping in African-Americans with equatorial Africans, as people from hot climates generally have slightly smaller crania.