Volta do mar

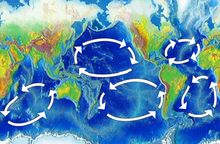

Lack of this information may have doomed the 13th-century expedition of Vandino and Ugolino Vivaldi, who were headed towards the Canary Islands (as yet unknown by the Europeans) and were lost; once there, without understanding the Atlantic gyre and the volta do mar, they would have been unable to beat upwind to the Strait of Gibraltar and home.

As India-bound Portuguese explorers and traders crossed the equator with the intention of passing the entire western coast of Africa, their voyages took them far to the West (in the vicinity of Brazil.)

The route of the Manila Galleon from Manila to Acapulco depended upon successful application of the Atlantic phenomenon to the Pacific Ocean: in discovering the North Pacific Gyre, captains of returning galleons had to reach the latitudes of Japan before they could safely cross.

The discovery, upon which the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade was based, is owed to the Spanish Andrés de Urdaneta, who, sailing in convoy under Miguel López de Legazpi, discovered the return route in 1565: the fleet split up, some heading south, but Urdaneta reasoned that the trade winds of the Pacific might move in a gyre as the Atlantic winds did.

If, in the Atlantic, ships made the Volta do mar to the west to pick up winds that would bring them back from Madeira, then, he reasoned, by sailing far to the north before heading east, he would pick up the westerlies to bring him back to the west coast of North America.