Quantum Hall effect

Since the electron density remains constant when the Fermi level is in a clean spectral gap, this situation corresponds to one where the Fermi level is an energy with a finite density of states, though these states are localized (see Anderson localization).

[1] The fractional quantum Hall effect is more complicated and still considered an open research problem.

[5] Actual measurements of the Hall conductance have been found to be integer or fractional multiples of e2/h to better than one part in a billion.

[10] Exact quantization in full generality is not completely understood but it has been explained as a very subtle manifestation of the combination of the principle of gauge invariance together with another symmetry (see Anomalies).

The integer quantum Hall effect instead is considered a solved research problem[11][12] and understood in the scope of TKNN formula and Chern–Simons Lagrangians.

[14] Currently it is considered an open research problem because no single, confirmed and agreed list of fractional quantum numbers exists, neither a single agreed model to explain all of them, although there are such claims in the scope of composite fermions and Non Abelian Chern–Simons Lagrangians.

This allows researchers to explore quantum effects by operating high-purity MOSFETs at liquid helium temperatures.

[18] The integer quantization of the Hall conductance was originally predicted by University of Tokyo researchers Tsuneya Ando, Yukio Matsumoto and Yasutada Uemura in 1975, on the basis of an approximate calculation which they themselves did not believe to be true.

[19] In 1978, the Gakushuin University researchers Jun-ichi Wakabayashi and Shinji Kawaji subsequently observed the effect in experiments carried out on the inversion layer of MOSFETs.

[20] In 1980, Klaus von Klitzing, working at the high magnetic field laboratory in Grenoble with silicon-based MOSFET samples developed by Michael Pepper and Gerhard Dorda, made the unexpected discovery that the Hall resistance was exactly quantized.

[12][22] Most integer quantum Hall experiments are now performed on gallium arsenide heterostructures, although many other semiconductor materials can be used.

[24] In two dimensions, when classical electrons are subjected to a magnetic field they follow circular cyclotron orbits.

Since the system is subjected to a magnetic field, it has to be introduced as an electromagnetic vector potential in the Schrödinger equation.

Then, a magnetic field is applied in the z direction and according to the Landau gauge the electromagnetic vector potential is

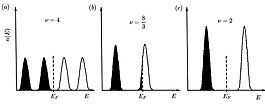

At zero field, the density of states per unit surface for the two-dimensional electron gas taking into account degeneration due to spin is independent of the energy As the field is turned on, the density of states collapses from the constant to a Dirac comb, a series of Dirac

Commonly it is assumed that the precise shape of Landau levels is a Gaussian or Lorentzian profile.

This fact called spin splitting implies that the density of states for each level is reduced by a half.

In order to get the number of occupied Landau levels, one defines the so-called filling factor

In actual experiments, one varies the magnetic field and fixes electron density (and not the Fermi energy!)

is a half-integer, the Fermi energy is located at the peak of the density distribution of some Landau Level.

This distribution of minimums and maximums corresponds to ¨quantum oscillations¨ called Shubnikov–de Haas oscillations which become more relevant as the magnetic field increases.

It is interesting to notice that if the magnetic field is very small, the longitudinal resistivity is a constant which means that the classical result is reached.

These states are localized in, for example, impurities of the material where they are trapped in orbits so they can not contribute to the conductivity.

By shooting the light across multiple mirrors, the photons are routed and gain additional phase proportional to their angular momentum.

Note, however, that the density of states in these regions of quantized Hall conductance is zero; hence, they cannot produce the plateaus observed in the experiments.

In the presence of disorder, which is the source of the plateaus seen in the experiments, this diagram is very different and the fractal structure is mostly washed away.

If this diagram is plotted as a function of filling factor, all the features are completely washed away, hence, it has very little to do with the actual Hall physics.

The observed strong similarity between integer and fractional quantum Hall effects is explained by the tendency of electrons to form bound states with an even number of magnetic flux quanta, called composite fermions.

The value of the von Klitzing constant may be obtained already on the level of a single atom within the Bohr model while looking at it as a single-electron Hall effect.

While during the cyclotron motion on a circular orbit the centrifugal force is balanced by the Lorentz force responsible for the transverse induced voltage and the Hall effect, one may look at the Coulomb potential difference in the Bohr atom as the induced single atom Hall voltage and the periodic electron motion on a circle as a Hall current.