Polymer

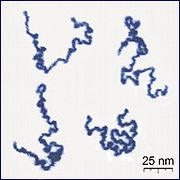

[3] A polymer (/ˈpɒlɪmər/[4][5]) is a substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers.

[6] Due to their broad spectrum of properties,[7] both synthetic and natural polymers play essential and ubiquitous roles in everyday life.

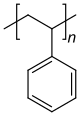

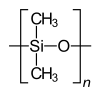

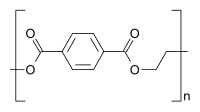

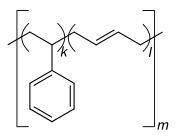

[8] Polymers range from familiar synthetic plastics such as polystyrene to natural biopolymers such as DNA and proteins that are fundamental to biological structure and function.

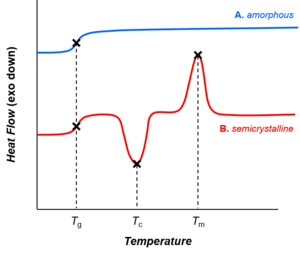

Their consequently large molecular mass, relative to small molecule compounds, produces unique physical properties including toughness, high elasticity, viscoelasticity, and a tendency to form amorphous and semicrystalline structures rather than crystals.

Historically, products arising from the linkage of repeating units by covalent chemical bonds have been the primary focus of polymer science.

[9][10] The modern concept of polymers as covalently bonded macromolecular structures was proposed in 1920 by Hermann Staudinger,[11] who spent the next decade finding experimental evidence for this hypothesis.

[16] Most commonly, the continuously linked backbone of a polymer used for the preparation of plastics consists mainly of carbon atoms.

The microstructure determines the possibility for the polymer to form phases with different arrangements, for example through crystallization, the glass transition or microphase separation.

In particular unbranched macromolecules can be in the solid state semi-crystalline, crystalline chain sections highlighted red in the figure below.

An important microstructural feature of a polymer is its architecture and shape, which relates to the way branch points lead to a deviation from a simple linear chain.

[28][29] The ratio of these two values (Mw / Mn) is the dispersity (Đ), which is commonly used to express the width of the molecular weight distribution.

[32] One important example of the physical consequences of the molecular weight is the scaling of the viscosity (resistance to flow) in the melt.

A synthetic polymer may be loosely described as crystalline if it contains regions of three-dimensional ordering on atomic (rather than macromolecular) length scales, usually arising from intramolecular folding or stacking of adjacent chains.

Viscoelasticity describes a complex time-dependent elastic response, which will exhibit hysteresis in the stress-strain curve when the load is removed.

In polymers, crystallization and melting do not suggest solid-liquid phase transitions, as in the case of water or other molecular fluids.

In the theta solvent, or the state of the polymer solution where the value of the second virial coefficient becomes 0, the intermolecular polymer-solvent repulsion balances exactly the intramolecular monomer-monomer attraction.

These strong hydrogen bonds, for example, result in the high tensile strength and melting point of polymers containing urethane or urea linkages.

[62] Polymer characterization spans many techniques for determining the chemical composition, molecular weight distribution, and physical properties.

Chlorine-induced cracking of acetal resin plumbing joints and polybutylene pipes has caused many serious floods in domestic properties, especially in the US in the 1990s.

Traces of chlorine in the water supply attacked polymers present in the plumbing, a problem which occurs faster if any of the parts have been poorly extruded or injection molded.

Attack of the acetal joint occurred because of faulty molding, leading to cracking along the threads of the fitting where there is stress concentration.

[63] Nylon 66 is susceptible to acid hydrolysis, and in one accident, a fractured fuel line led to a spillage of diesel into the road.

If diesel fuel leaks onto the road, accidents to following cars can be caused by the slippery nature of the deposit, which is like black ice.

The latex sap of "caoutchouc" trees (natural rubber) reached Europe in the 16th century from South America long after the Olmec, Maya and Aztec had started using it as a material to make balls, waterproof textiles and containers.

The behaviour of polymers was initially rationalised according to the theory proposed by Thomas Graham which considered them as colloidal aggregates of small molecules held together by unknown forces.

Notwithstanding the lack of theoretical knowledge, the potential of polymers to provide innovative, accessible and cheap materials was immediately grasped.

The work carried out by Braconnot, Parkes, Ludersdorf, Hayward and many others on the modification of natural polymers determined many significant advances in the field.

In 1920, Hermann Staudinger published his seminal work "Über Polymerisation",[66] in which he proposed that polymers were in fact long chains of atoms linked by covalent bonds.

[67] After the 1930s polymers entered a golden age during which new types were discovered and quickly given commercial applications, replacing naturally-sourced materials.

This development was fuelled by an industrial sector with a strong economic drive and it was supported by a broad academic community that contributed innovative syntheses of monomers from cheaper raw material, more efficient polymerisation processes, improved techniques for polymer characterisation and advanced, theoretical understanding of polymers.