Vorticism

[2] In the summer of 1913 Roger Fry, with Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, set up the Omega Workshops in Fitzrovia – in the heart of bohemian London.

Fry was an advocate of an increasingly abstract art and design practice, and the studio/gallery/retail outlet allowed him to employ and support artists in sympathy with this approach, such as Wyndham Lewis, Frederick Etchells, Cuthbert Hamilton and Edward Wadsworth.

[4] Lewis curated the exhibition's 'Cubist Room' and provided a written introduction in which he attempted to cohere the various strands of abstraction on display: 'These painters are not accidently [sic?]

[6] Financed by Lewis's painter friend Kate Lechmere, the Rebel Art Centre was established in March 1914 at 38 Great Ormond Street.

[21] Lewis, Pound and Gaudier-Brzeska were at the intellectual heart of the project, but Roberts's later comments suggest that most of the group were not made aware of the manifesto's contents before publication.

[22] Jacob Epstein was presumably too established to be co-opted as a signatory, and David Bomberg had threatened Lewis with legal action if his work was reproduced in BLAST and made his independence very clear through a one-man show at the Chenil Galleries, also in July, where his large abstract painting Mud Bath was prominently displayed outside above the entrance.

There would be little appetite for avant-garde art at this time of national and international crisis; however, a ‘Vorticist Exhibition’ went ahead at the Doré Galleries in New Bond Street the following year.

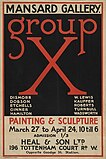

[33] Jessica Dismorr and Dorothy Shakespear (Ezra Pound's wife) joined a slightly broader range of artists that also included Jacob Kramer and Nevinson.

[34] Ezra Pound had been championing Wyndham Lewis's work from 1915 with a successful New York lawyer and art collector, John Quinn.

[39] However, Wadsworth, unexpectedly, was able to pursue his artistic interests through the supervision of the dazzle camouflage being applied to over two thousand ships, largely at Bristol and Liverpool.

Nevertheless, Lewis, Wadsworth, Roberts and Atkinson all had one-man shows by the early 1920s – each artist navigating his own path between modernism and potentially more saleable recognisable subjects.

An anecdote recorded by Brigid Peppin relates how Helen Saunders's sister used a Vorticist oil to cover her larder floor and '[it was] worn to destruction'[48] – an extreme example of how the paintings were not appreciated.

'[50] Despite a resurgence of abstract art in Britain in the middle years of the twentieth century, the contribution of Vorticism was largely forgotten until a spat between John Rothenstein of the Tate Gallery and William Roberts blew up in the press.

[54] Five years later, the exhibition 'Vorticism and Its Allies' curated by Richard Cork at the Hayward Gallery, London,[55] went further in painstakingly bringing together paintings, drawings, sculpture (including a reconstruction of Epstein's Rock Drill 1913–15), Omega Workshop artefacts, photographs, journals, catalogues, letters and cartoons.

[58] The curators, Mark Antliff and Vivien Greene, had also traced some previously lost works (such as three paintings by Helen Saunders) that were included in the exhibition.