Voynich manuscript

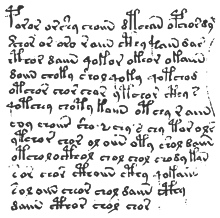

Based on modern analysis using polarized light microscopy (PLM), it has been determined that a quill pen and iron gall ink were used for the text and figure outlines.

[29] Computer scientist Jorge Stolfi of the University of Campinas highlighted that parts of the text and drawings have been modified, using darker ink over a fainter, earlier script.

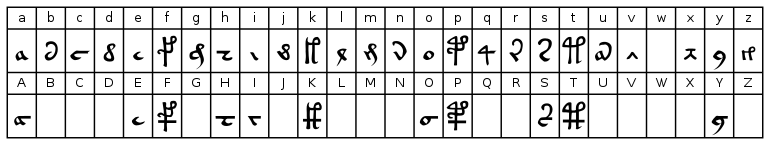

[38] The first major one was created by the "First Study Group", led by cryptographer William F. Friedman in the 1940s, where each line of the manuscript was transcribed to an IBM punch card to make it machine readable.

[46] In 2014, a team led by Diego Amancio of the University of São Paulo published a study using statistical methods to analyse the relationships of the words in the text.

[55] Astrological considerations frequently played a prominent role in herb gathering, bloodletting, and other medical procedures common during the likeliest dates of the manuscript.

On this point I suspend judgement; it is your place to define for us what view we should take thereon, to whose favor and kindness I unreservedly commit myself and remain At the command of your Reverence, Joannes Marcus Marci of Cronland

[56] No records of the book for the next 200 years have been found, but in all likelihood, it was stored with the rest of Kircher's correspondence in the library of the Collegio Romano (now the Pontifical Gregorian University).

[16] Kircher's correspondence was among those books, and so, apparently, was the Voynich manuscript, as it still bears the ex libris of Petrus Beckx, head of the Jesuit order and the university's rector at the time.

[12][16] Beckx's private library was moved to the Villa Mondragone, Frascati, a large country palace near Rome that had been bought by the Society of Jesus in 1866 and housed the headquarters of the Jesuits' Ghislieri College.

Marci's 1665/1666 cover letter to Kircher says that, according to his friend the late Raphael Mnishovsky, the book had once been bought by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia for 600 ducats, 67.5 ozt (2.10 kg) of actual gold weight.

It was thought possible, prior to the carbon dating of the manuscript, that Dee or Kelley might have written it and spread the rumour that it was originally a work of Bacon's in the hopes of later selling it.

[73] In his 2006 book, Nick Pelling proposed that the Voynich manuscript was written by 15th-century North Italian architect Antonio Averlino (also known as "Filarete"), a theory broadly consistent with the radiocarbon dating.

For example, the first two lines of page f15v contain "oror or" and "or or oro r", which strongly resemble how Roman numerals such as "CCC" or "XXXX" would look if verbosely enciphered.

[79] Child (1976),[80] a linguist of Indo-European languages for the U.S. National Security Agency, proposed that the manuscript was written in a "hitherto unknown North Germanic dialect".

[5] The fact that the manuscript has defied decipherment thus far has led various scholars to propose that the text does not contain meaningful content in the first place, implying that it may be a medieval hoax.

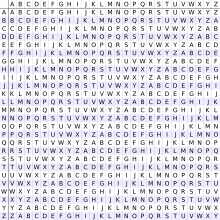

In 2003, computer scientist Gordon Rugg showed that text with characteristics similar to the Voynich manuscript could have been produced using a table of word prefixes, stems, and suffixes, which would have been selected and combined by means of a perforated paper overlay.

Some maintain that the similarity between the pseudo-texts generated in Gordon Rugg's experiments and the Voynich manuscript is superficial, and the grille method could be used to emulate any language to a certain degree.

[95] With this evidence, he believes it unlikely that these features were intentionally "incorporated" into the text to make a hoax more realistic, as most of the required academic knowledge of these structures did not exist at the time the Voynich manuscript would have been written.

Their conclusion is that clusters derived by computation match with the topics of the illustrations to some degree, thus providing evidence that the Voynich manuscript contains meaningful text.

[99] In 2022, Yale University researchers Daniel Gaskell and Claire Bowern published the results of an experiment in which human participants intentionally tried to write meaningless text.

[100] In their 2004 book, Gerry Kennedy and Rob Churchill suggest the possibility that the Voynich manuscript may be a case of glossolalia (speaking-in-tongues), channelling, or outsider art.

Kennedy and Churchill use Hildegard von Bingen's works to point out similarities between the Voynich manuscript and the illustrations that she drew when she was suffering from severe bouts of migraine, which can induce a trance-like state prone to glossolalia.

His singular hypothesis held that the visible text is meaningless, but that each apparent "letter" is in fact constructed of a series of tiny markings discernible only under magnification.

Newbold claimed to have used this knowledge to work out entire paragraphs proving the authorship of Bacon and recording his use of a compound microscope four hundred years before van Leeuwenhoek.

A circular drawing in the astronomical section depicts an irregularly shaped object with four curved arms, which Newbold interpreted as a picture of a galaxy, which could be obtained only with a telescope.

[17] Leonell C. Strong, a cancer research scientist and amateur cryptographer, claimed that the solution to the Voynich manuscript was a "peculiar double system of arithmetical progressions of a multiple alphabet".

[68]: 252 In 1978, Robert Brumbaugh, a professor of classical and medieval philosophy at Yale University, claimed that the manuscript was a forgery intended to fool Emperor Rudolf II into purchasing it, and that the text is Latin enciphered with a complex, two-step method.

[86] Greg Kondrak, a professor of natural language processing at the University of Alberta, and his graduate student Bradley Hauer used computational linguistics in an attempt to decode the manuscript.

[108] Their findings were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics in August 2017 in the form of an article suggesting that the manuscript's language is most likely Hebrew, but encoded using alphagrams, i.e. alphabetically ordered anagrams.

[135] In 2004, the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library made high-resolution digital scans publicly available online, and several printed facsimiles appeared.