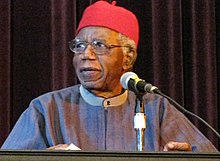

Chinua Achebe

[1][a] His father, Isaiah Okafo Achebe, was a teacher and evangelist, and his mother, Janet Anaenechi Iloegbunam, was the daughter of a blacksmith from Awka,[3] a leader among church women, and a vegetable farmer.

The Achebe family had five other surviving children, named in a fusion of traditional words relating to their new religion: Frank Okwuofu, John Chukwuemeka Ifeanyichukwu, Zinobia Uzoma, Augustine Ndubisi, and Grace Nwanneka.

His education was furthered by the collages his father hung on the walls of their home, as well as almanacs and numerous books—including a prose adaptation of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream (c. 1590) and an Igbo version of Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (1678).

To compensate, the government provided a bursary, and his family donated money—his older brother Augustine gave up money for a trip home from his job as a civil servant so Achebe could continue his studies.

[30] While pondering possible career paths, Achebe was visited by a friend from the university, who convinced him to apply for an English teaching position at the Merchants of Light school at Oba.

It was a ramshackle institution with a crumbling infrastructure and a meagre library; the school was built on what the residents called "bad bush"—a section of land thought to be tainted by unfriendly spirits.

He cut away the second and third sections of the book, leaving only the story of a yam farmer named Okonkwo who lives during the colonization of Nigeria and struggles with his father's debtor legacy.

[50] In 1960 Achebe published No Longer at Ease, a novel about a civil servant named Obi, grandson of Things Fall Apart's main character, who is embroiled in the corruption of Lagos.

[51] Obi undergoes the same turmoil as much of the Nigerian youth of his time; the clash between the traditional culture of his clan, family, and home village against his government job and modern society.

[60] VON struggled to maintain neutrality when Nigerian Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa declared a state of emergency in the Western Region, responding to a series of conflicts between officials of varying parties.

Among the topics of discussion was an attempt to determine whether the term African literature ought to include work from the diaspora, or solely that writing composed by people living within the continent itself.

Writing about the conference in several journals, Achebe hailed it as a milestone for the literature of Africa, and highlighted the importance of community among isolated voices on the continent and beyond.

[62] While at Makerere, Achebe was asked to read a novel written by a student named James Ngugi (later known as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o) called Weep Not, Child.

[65] Achebe published an essay entitled "Where Angels Fear to Tread" in the December 1962 issue of Nigeria Magazine in reaction to critiques African work was receiving from international authors.

[70] He drew further inspiration a year later when he viewed a collection of Igbo objects excavated from the area by archaeologist Thurstan Shaw; Achebe was startled by the cultural sophistication of the artefacts.

[74] In a letter written to Achebe, American writer John Updike expressed his surprised admiration for the sudden downfall of Arrow of God's protagonist and praised the author's courage to write "an ending few Western novelists would have contrived".

[68] Achebe responded by suggesting that the individualistic hero was rare in African literature, given its roots in communal living and the degree to which characters are "subject to non-human forces in the universe".

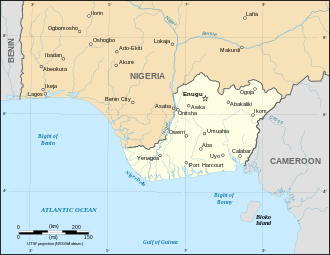

[79] Once the family had resettled in Enugu, Achebe and his friend Christopher Okigbo started a publishing house called Citadel Press to improve the quality and increase the quantity of literature available to younger readers.

[92] In October of the same year, Achebe joined writers Cyprian Ekwensi and Gabriel Okara for a tour of the United States to raise awareness about the dire situation in Biafra.

[96] After the war, Achebe helped start two magazines in 1971: the literary journal Okike, a forum for African art, fiction, and poetry;[97] and Nsukkascope, an internal publication of the university.

[109] When he returned to the University of Nigeria, he hoped to accomplish three goals: finish the novel he had been writing, renew the native publication of Okike, and further his study of Igbo culture.

Critic Nahem Yousaf highlights the importance of these depictions: "Around the tragic stories of Okonkwo and Ezeulu, Achebe sets about textualising Igbo cultural identity".

[143] The portrayal of indigenous life is not simply a matter of literary background, he adds: "Achebe seeks to produce the effect of a precolonial reality as an Igbo-centric response to a Eurocentrically constructed imperial 'reality' ".

[147] The colonial impact on the Igbo in Achebe's novels is often affected by individuals from Europe, but institutions and urban offices frequently serve a similar purpose.

[148] Having shown his acumen for portraying traditional Igbo culture in Things Fall Apart, Achebe demonstrated in No Longer at Ease an ability to depict modern Nigerian life.

"[152] His perspective is reflected in the words of Ikem, a character in Anthills of the Savannah: "whatever you are is never enough; you must find a way to accept something, however small, from the other to make you whole and to save you from the mortal sin of righteousness and extremism.

He has been criticised as a sexist author, in response to what many call the uncritical depiction of traditionally patriarchal Igbo society, where the most masculine men take numerous wives, and women are beaten regularly.

[158] According to Bestman, in Things Fall Apart Okonkwo's furious manhood overpowers everything "feminine" in his life, including his own conscience, while Achebe's depiction of the chi, or personal god, has been called the "mother within".

[160] His obsession with maleness is fueled by an intense fear of femaleness, which he expresses through the physical and verbal abuse of his wives, his violence towards his community, his constant worry that his son Nwoye is not manly enough, and his wish that his daughter Ezinma had been born a boy.

Soyinka denied such requests, explaining that Achebe "is entitled to better than being escorted to his grave with that monotonous, hypocritical aria of deprivation's lament, orchestrated by those who, as we say in my part of the world, 'dye their mourning weeds a deeper indigo than those of the bereaved'.