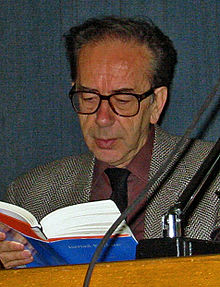

Ismail Kadare

[4][5][6] Living in Albania during a time of strict censorship, he devised stratagems to outwit Communist censors who had banned three of his books, using devices such as parable, myth, fable, folk-tale, allegory, and legend, sprinkled with double-entendre, allusion, insinuation, satire, and coded messages.

In 1996, France made him a foreign associate of the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, and in 2016, he was a Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur recipient.

The New York Times wrote that he was a national figure in Albania comparable in popularity perhaps to Mark Twain in the United States, and that "there is hardly an Albanian household without a Kadare book".

He was born in Gjirokastër, a historic Ottoman fortress–city in the mountains, made up of tall stone houses in what is today southern Albania, a dozen miles from the border with Greece.

[29][11][30] At age 12, Kadare wrote his first short stories, which were published in the Pionieri (Pioneer) journal in Tirana, a communist magazine for children.

[34] In Moscow he met writers united under the banner of Socialist Realism—a style of art characterized by the idealized depiction of revolutionary communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat.

Kadare also had the opportunity to read contemporary Western literature, including works by Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Ernest Hemingway.

[39] During his time in the Soviet Union, Kadare published a collection of poetry in Russian, and in 1959 also wrote his first novel, Qyteti pa reklama (The City Without Signs), a critique of socialist careerism in Albania.

Locally inspired, the poem transforms the centuries-old myth of the legendary 15th century Princess Argjiro, who was said to have jumped off Gjirokastër Castle along with her child to avoid being captured by the Ottomans.

[63] Kadare's enemies in the secret police and the old guard of the Albanian Politburo referred to him as an agent of the West, which was one of the most dangerous accusations that could be made in Albania.

[46] John Updike wrote in The New Yorker, that it was "a thoroughly enchanting novel — sophisticated and accomplished in its poetic prose and narrative deftness, yet drawing resonance from its roots in one of Europe's most primitive societies".

[65] Throughout the 1970s, Kadare began to work more with myths, legends, and the distant past, often drawing allusions between the Ottoman Empire and present-day Albania.

[71] At this time, he also worked as an editor and contributor to New Albania, an arts and culture magazine which sought to promote Albanian socialism to a worldwide audience.

[74] After Kadare offended the authorities with a political poem entitled "The Red Pasha" in 1975 that poked fun at the Albanian Communist bureaucracy, he was denounced, narrowly avoiding being shot, and was ultimately sent to do manual labour in a remote village deep in the central Albania countryside for a short time.

[37] In 1980 Kadare published the novel Broken April, about the centuries-old tradition of hospitality, blood feuds, and revenge killing in the highlands of north Albania in the 1930s.

[78][79] The New York Times, reviewing it, wrote: "Broken April is written with masterly simplicity in a bardic style, as if the author is saying: Sit quietly and let me recite a terrible story about a blood feud and the inevitability of death by gunfire in my country.

The following year, under the same title, Kadare published the completed novel in the second edition of Emblema e dikurshme (Signs of the Past); despite its political themes, it was not censored by the Albanian authorities.

[11] Kadare was accused of attacking the government in a covert manner, and the novel was viewed by the authorities as an anticommunist work and a mockery of the political system.

[91] Communist Albanian leader Enver Hoxha presided over a Stalinist regime of forced collectivization and suppression from the end of World War II until 1985.

[94] Albanian historian and scholar Anton Logoreci described Kadare during this time as "a rare sturdy flower growing, inexplicably, in a largely barren patch".

On the evening of the ailing dictator's death, members of the Union of Writers, the Albanian Politburo, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party hastily organized a meeting in order to condemn Moonlit Night.

[75] In October 1990, after he criticized the Albanian government, urged democratization of isolationist Albania – Europe's last Communist-ruled country, then with a population of 3.3 million – and faced the ire of its authorities and threats from the Sigurimi secret police, Kadare sought and received political asylum in France.

[76][104] The New York Times wrote that he was a national figure in Albania comparable in popularity perhaps to Mark Twain in the United States, and that "there is hardly an Albanian household without a Kadare book, and even foreign visitors are presented with volumes of his verse as souvenirs".

[110] It deals with a group of foreigners who are touring Eastern Europe after the fall of Communism and hear exciting rumours during their stay in Albania about the capture of the spirit from the dead.

[115][116][117] He was granted a state funeral on 3 July at the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet in Tirana, but was buried in a private ceremony shortly afterwards.

[120] In 2003 he received the Ovid Prize international award in Romania, and the Presidential Gold Medal of the League of Prizren from the President of Kosovo.

[132] Kadare won the 2019 Park Kyong-ni Prize, an international award based in South Korea, for his literary works during his career.

[137] Kadare was nominated for the 2020 Neustadt International Prize for Literature (described as the "American Nobel") in the United States by Bulgarian writer Kapka Kassobova.

[149][11] He used old devices such as parable, myth, fable, folk-tale, allegory, and legend, and sprinkled them with double-entendre, allusion, insinuation, satire, and coded messages.

[152] The conditions in which Kadare lived and published his works were not comparable to other European Communist countries where at least some level of public dissent was tolerated.