W. H. Auden

Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, form, and content.

Auden moved to the United States partly to escape this reputation, and his work in the 1940s, including the long poems "For the Time Being" and "The Sea and the Mirror", focused on religious themes.

Auden was a prolific writer of prose essays and reviews on literary, political, psychological, and religious subjects, and he worked at various times on documentary films, poetic plays, and other forms of performance.

Critical views on his work ranged from sharply dismissive (treating him as a lesser figure than W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot) to strongly affirmative (as in Joseph Brodsky's statement that he had "the greatest mind of the twentieth century").

[8] Auden, whose grandfathers were both Church of England clergymen, grew up in an Anglo-Catholic household that followed a "high" form of Anglicanism, with doctrine and ritual resembling those of Catholicism.

[11] His family moved to Homer Road in Solihull, near Birmingham, in 1908,[10] where his father had been appointed the School Medical Officer and Lecturer (later Professor) of Public Health.

[17] At thirteen he went to Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk; there, in 1922, when his friend Robert Medley asked him if he wrote poetry, Auden first realised his vocation was to be a poet.

[24] From his Oxford years onward, Auden's friends uniformly described him as funny, extravagant, sympathetic, generous, and, partly by his own choice, lonely.

[9] At the Downs, in June 1933, he experienced what he later described as a "Vision of Agape", while sitting with three fellow teachers at the school, when he suddenly found that he loved them for themselves, that their existence had infinite value for him; this experience, he said, later influenced his decision to return to the Anglican Church in 1940.

[32] From 1935 until he left Britain early in 1939, Auden worked as freelance reviewer, essayist, and lecturer, first with the GPO Film Unit, a documentary film-making branch of the post office, headed by John Grierson.

His seven-week visit to Spain affected him deeply, and his social views grew more complex as he found political realities to be more ambiguous and troubling than he had imagined.

He was embarrassed if they were publicly revealed, as when his gift to his friend Dorothy Day for the Catholic Worker movement was reported on the front page of The New York Times in 1956.

[42] On his return, he settled in Manhattan, working as a freelance writer, a lecturer at The New School for Social Research, and a visiting professor at Bennington, Smith, and other American colleges.

[49][50] Following some years of lobbying by his friend David Luke, Auden's old college, Christ Church, in February 1972 offered him a cottage on its grounds to live in; he moved his books and other possessions from New York to Oxford in September 1972,[51] while continuing to spend summers in Austria with Kallman.

Auden died at 66 of heart failure at the Altenburgerhof Hotel in Vienna overnight on 28–29 September 1973, a few hours after giving a reading of his poems for the Austrian Society for Literature at the Palais Pálffy.

His poetry was encyclopaedic in scope and method, ranging in style from obscure twentieth-century modernism to the lucid traditional forms such as ballads and limericks, from doggerel through haiku and villanelles to a "Christmas Oratorio" and a baroque eclogue in Anglo-Saxon meters.

[54] The tone and content of his poems ranged from pop-song clichés to complex philosophical meditations, from the corns on his toes to atoms and stars, from contemporary crises to the evolution of society.

His literary executor, Edward Mendelson, argues in his introduction to Selected Poems that Auden's practice reflected his sense of the persuasive power of poetry and his reluctance to misuse it.

[58] In 1928 he wrote his first dramatic work, Paid on Both Sides, subtitled "A Charade", which combined style and content from the Icelandic sagas with jokes from English school life.

[54][29] Auden's next large-scale work was The Orators: An English Study (1932; revised editions, 1934, 1966), in verse and prose, largely about hero-worship in personal and political life.

"[62] His next play The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), written in collaboration with Isherwood, was similarly a quasi-Marxist updating of Gilbert and Sullivan in which the general idea of social transformation was more prominent than any specific political action or structure.

[29] Among the poems included in the book are "Hearing of harvests", "Out on the lawn I lie in bed", "O what is that sound", "Look, stranger, on this island now" (later revised versions change "on" to "at"), and "Our hunting fathers".

[29][10] Auden's shorter poems now engaged with the fragility and transience of personal love ("Danse Macabre", "The Dream", "Lay your sleeping head"), a subject he treated with ironic wit in his "Four Cabaret Songs for Miss Hedli Anderson" (which included "Tell Me the Truth About Love" and the revised version of "Funeral Blues"), and also the corrupting effect of public and official culture on individual lives ("Casino", "School Children", "Dover").

[54][42] His prose book The Dyer's Hand (1962) gathered many of the lectures he gave in Oxford as Professor of Poetry in 1956–61, together with revised versions of essays and notes written since the mid-1940s.

[9] His last books of verse, Epistle to a Godson (1972) and the unfinished Thank You, Fog (published posthumously, 1974) include reflective poems about language ("Natural Linguistics", "Aubade"), philosophy and science ("No, Plato, No", "Unpredictable but Providential"), and his own aging ("A New Year Greeting", "Talking to Myself"—which he dedicated to his friend Oliver Sacks,[71][72] "A Lullaby" ["The din of work is subdued"]).

"[78] But John Sparrow, recalling Mitchison's comment in 1934, dismissed Auden's early work as "a monument to the misguided aims that prevail among contemporary poets, and the fact that... he is being hailed as 'a master' shows how criticism is helping poetry on the downward path.

[92] By the time of his death in 1973 he had attained the status of a respected elder statesman, and a memorial stone for him was placed in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey in 1974.

[102] Overall Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, form and content.

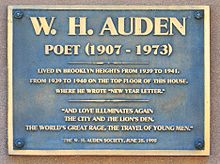

[29][54][77][103] Memorial stones and plaques commemorating Auden include those in Westminster Abbey; at his birthplace at 55 Bootham, York;[104] near his home on Lordswood Road, Birmingham;[105] in the chapel of Christ Church, Oxford; on the site of his apartment at 1 Montague Terrace, Brooklyn Heights; at his apartment in 77 St. Marks Place, New York (damaged and now removed);[106] at the site of his death at Walfischgasse 5 in Vienna;[107] and in the Rainbow Honor Walk in San Francisco.

[109] In 2023, newly declassified UK government files revealed that Auden was considered as a candidate to be the new Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom in 1967 following the death of John Masefield.