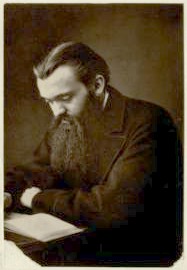

William Kingdon Clifford

Born in Exeter, William Clifford was educated at Doctor Templeton's Academy on Bedford Circus and showed great promise at school.

[7] In 1871, he was appointed professor of mathematics and mechanics at University College London, and in 1874 became a fellow of the Royal Society.

The field of intrinsic differential geometry was born, with the concept of curvature broadly applied to space itself as well as to curved lines and surfaces.

His report at Cambridge, "On the Space-Theory of Matter", was published in 1876, anticipating Albert Einstein's general relativity by 40 years.

He published papers on a range of topics including algebraic forms and projective geometry and the textbook Elements of Dynamic.

The former symbolizes his metaphysical conception, suggested to him by his reading of Baruch Spinoza,[5] which Clifford (1878) defined as follows:[18] That element of which, as we have seen, even the simplest feeling is a complex, I shall call Mind-stuff.

When matter takes the complex form of a living human brain, the corresponding mind-stuff takes the form of a human consciousness, having intelligence and volition.Regarding Clifford's concept, Sir Frederick Pollock wrote: Briefly put, the conception is that mind is the one ultimate reality; not mind as we know it in the complex forms of conscious feeling and thought, but the simpler elements out of which thought and feeling are built up.

[5] Tribal self, on the other hand, gives the key to Clifford's ethical view, which explains conscience and the moral law by the development in each individual of a 'self,' which prescribes the conduct conducive to the welfare of the 'tribe.'

Animated by an intense love of his conception of truth and devotion to public duty, he waged war on such ecclesiastical systems as seemed to him to favour obscurantism, and to put the claims of sect above those of human society.

The alarm was greater, as theology was still unreconciled with Darwinism; and Clifford was regarded as a dangerous champion of the anti-spiritual tendencies then imputed to modern science.

[5] There has also been debate on the extent to which Clifford's doctrine of 'concomitance' or 'psychophysical parallelism' influenced John Hughlings Jackson's model of the nervous system and, through him, the work of Janet, Freud, Ribot, and Ey.

[19] In his 1877 essay, The Ethics of Belief, Clifford argues that it is immoral to believe things for which one lacks evidence.

"[20] As such, he is arguing in direct opposition to religious thinkers for whom 'blind faith' (i.e. belief in things in spite of the lack of evidence for them) was a virtue.

Though Clifford never constructed a full theory of spacetime and relativity, there are some remarkable observations he made in print that foreshadowed these modern concepts: In his book Elements of Dynamic (1878), he introduced "quasi-harmonic motion in a hyperbola".

Elsewhere he states:[21] This passage makes reference to biquaternions, though Clifford made these into split-biquaternions as his independent development.

In 1910, William Barrett Frankland quoted the Space-Theory of Matter in his book on parallelism: "The boldness of this speculation is surely unexcelled in the history of thought.

Hermann Weyl (1923), for instance, mentioned Clifford as one of those who, like Bernhard Riemann, anticipated the geometric ideas of relativity.

[23] In 1940, Eric Temple Bell published The Development of Mathematics, in which he discusses the prescience of Clifford on relativity:[24] John Archibald Wheeler, during the 1960 International Congress for Logic, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science (CLMPS) at Stanford, introduced his geometrodynamics formulation of general relativity by crediting Clifford as the initiator.

[25] In The Natural Philosophy of Time (1961), Gerald James Whitrow recalls Clifford's prescience, quoting him in order to describe the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric in cosmology.

"[29] In 1992, Farwell and Knee continued their study of Clifford and Riemann:[30][They] hold that once tensors had been used in the theory of general relativity, the framework existed in which a geometrical perspective in physics could be developed and allowed the challenging geometrical conceptions of Riemann and Clifford to be rediscovered.

""There is no scientific discoverer, no poet, no painter, no musician, who will not tell you that he found ready made his discovery or poem or picture—that it came to him from outside, and that he did not consciously create it from within.

""If a man, holding a belief which he was taught in childhood or persuaded of afterwards, keeps down and pushes away any doubts which arise about it in his mind, purposely avoids the reading of books and the company of men that call in question or discuss it, and regards as impious those questions which cannot easily be asked without disturbing it—the life of that man is one long sin against mankind.