W. Coleman Nevils

After completing several Collegiate Gothic buildings, work on the Greater Georgetown plan stalled because of the Great Depression.

Though near retirement, Nevils became the first Jesuit president of the University of Scranton in 1942, after the Lasallian Brothers departed the school.

He led the university through a change in administration, and the decline of enrollment due to World War II.

Nevils returned to New York City in 1947, and became the head of America magazine, and the superior of Campion House, the residence for the Jesuit editors of the publication.

[4] In 1919, he simultaneously became the chancellor (academic vice president) of the university,[5][1] and in 1920, was made the regent of the School of Foreign Service.

[9] His inauguration in late October was attended by representatives of 93 American and foreign universities, 26 learned societies, and members of the diplomatic corps, forming the largest gathering of educators ever held at a Catholic college in the United States.

He revived the board of regents as a body focused on fundraising, and appointed alumni, as well as business leaders without any connection to Georgetown.

[12] He also abolished an abbreviated two-year pre-medical program, requiring students intending to go to medical school to complete the standard four-year undergraduate curriculum.

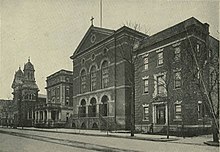

The most ambitious portion of the Greater Georgetown plan was the creation of a new Collegiate Gothic quadrangle, designed by the Philadelphia architect Emile G. Perrot, which would be enclosed by Healy Hall and three new buildings.

[18] While the original Greater Georgetown plan envisioned the quadrangle being named for the alumnus and Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, Nevils instead changed the name to the Andrew White Memorial Quadrangle, after the early Jesuit missionary to the United States.

With funds already secured, the depression actually worked in favor of the university, as it drove down the cost of construction, and the project was finished under budget.

Fundraising for the second building, which would contain chemistry laboratories, classrooms, and administrative offices was more difficult,[19] but construction was able to begin in June 1932.

Rising four stories, its facade was composed of granite quarried from northern Maryland and gray stone repurposed from a recently dismantled bridge spanning Rock Creek.

[27] He then returned to Washington in 1940, where while living at Georgetown Preparatory School, he wrote a book about the history of the Jesuits in the United States, in commemoration of the 400th anniversary of the founding of the order.

[27] While in Washington, Nevils lectured on sacred eloquence at Woodstock College,[17] and developed a reputation as a talented and sought-after preacher.

[29] The Jesuits accepted, and Hafey announced the change to the public on June 12; three days later, the Lasallian Brothers left Scranton.

[30] In the interim of the Brothers' departure and the Jesuits' full arrival, the school was run by a layman, Frank O'Hara, as the acting chief executive.

[31] With the number of students eventually reduced, the university's sole academic building, Old Main, accommodated all of its classrooms and administrative offices.

[7] To offset some of the declining enrollment, the university created an aviation program that trained cadets for the Army Air Corps and the Navy.

[7] Shortly after renovating the old Thomson Hospital, known as the annex, it suffered a fire on December 23, 1943, which nearly destroyed the building.

[31] The curriculum of the University of Scranton was improved to more closely align with the Ratio Studiorum, which placed a heavier emphasis on philosophy and logic.

[31] Nevils sought to establish good relations with the community, frequently speaking before local civic and religious associations.

To accommodate this surge in enrollment, Nevils began leasing space in downtown Scranton, and holding day, twilight, and evening classes.

[37] Throughout his life, Nevils had been honored by the governments of Yugoslavia, Chile, Romania, Czechoslovakia, France, and Jerusalem,[1] and was admitted to the Order of the Crown of Italy in 1933.