Wages for housework

It was started in 1972 by Mariarosa Dalla Costa,[1] Silvia Federici,[2] Brigitte Galtier, and Selma James[3] who first put forward the demand for wages for housework.

In Padua, Italy, a group called Lotta Feminista, formed by Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Silvia Federici, adopted the idea of Wages for Housework.

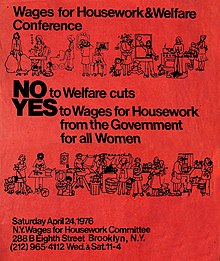

8th St. Flyers handed out in support of the New York Wages for Housework Committee called for all women to join regardless of marital status, nationality, sexual orientation, number of children, or employment.

It is called Payday men's network and works closely with IWFHC and the Global Women's Strike in London and Philadelphia especially and is active with conscientious objectors and refuseniks in a number of countries.

[citation needed] The Italian Padua group led by Dalla Costa, who was close to Federici, left the IWFHC and dissolved not long after.

Black Women for Wages for Housework carried on in New York and in London (a group had also started in Bristol in 1976, and later branches formed in Los Angeles and San Francisco).

IWFHC had an anti-war and anti-militarist perspective from the start, and called for the funds to pay for unwaged caring work to come from military budgets.

In 2019 the Global Women's Strike (GWS) network and Wages for Housework Campaign joined a coalition of organizations calling for a Green New Deal for Europe (GNDE).

These campaigns include: ending poverty, welfare cuts, detention, deportation; a living wage/care income for mothers and other carers; domestic workers' rights'; pay equity; justice for survivors of rape and domestic violence; challenging racism, disability racism, queer discrimination, transphobia; decriminalizing sex work; stopping the state taking children from their mothers; opposing apartheid, war, genocide, military occupation, corporate land grabs; supporting human rights defenders and refuseniks; ending the death penalty and solitary confinement .

Instead feminists should focus on increasing women's opportunities in the paid workforce with pay equity, while promoting a more equal distribution of unpaid work in the household.

Proponents of Wages for Housework also support equal opportunity and pay equity, however, they argue that entering the workforce does not sufficiently challenge the social role of women in the household nor result in a more equitable distribution of unpaid care work.

[32] Other criticisms include the concern that providing wages for housework would commodify intimate human relationships of love and care and would subsume them into capitalist relations.

For instance, according to Silvia Federici the demand for wages for housework is not just about remuneration for unpaid work or women's financial empowerment and independence.

[31] The payment of wages for housework would also require capital to pay for the immense amount of unpaid care work (undertaken largely by women) that currently reproduces the labor force.

[33][34] This amounts to an enormous subsidy to the capitalist economy, and paying for it would likely render the current system uneconomic, subverting the social relations in the process.

Instead they have promoted public funding for these schemes as part of a larger project of recognizing and revaluing the indispensable role of unpaid care work for society and the economy.

Some feminist scholars have also called for the creation of new commons-based systems of care and basic provisioning that operate outside of the market and state, and for the defense of existing commons, especially in communities of the Global South.

[36] She asserts that "wives, as earners through domestic service, are entitled to the wages of cooks, housemaids, nursemaids, seamstresses, or housekeepers" and that providing women economic independence is key to their liberation.

Alva Myrdal, a Swedish feminist, focused on state sponsored child care and housing, in order to ease the burden of parenting off mothers.

The Women of the World Are Serving Notice!

We want wages for

every dirty toilet

every indecent assault

every painful childbirth

every cup of coffee

and every smile

and if we don't get

what we want we

will simply refuse

to work any longer!