Walloons

The Walloon language, widespread in use up until the Second World War, has been dying out of common use due in part to its prohibition by the public school system, in favor of French.

Many non-French-speaking observers (over)generalize Walloons as a term of convenience for all Belgian French-speakers (even those born and living in the Brussels-Capital Region).

After a brief period with Dutch as the official language while the region was part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, the people reinstated French after achieving independence in 1830.

The heartland of Walloon culture are the Meuse and Sambre river valleys, Charleroi, Dinant, Namur (the regional capital), Huy, Verviers, and Liège.

However, the entire French-speaking population of Wallonia cannot be culturally considered Walloon, since a significant portion in the west (around Tournai and Mons) and smaller portions in the extreme south (around Arlon) possess other languages as mother tongues (namely, Picard, Champenois, Lorrain, Flemish, German and Luxembourgish).

[24] Based on other surveys and figures, Laurent Hendschel wrote in 1999 that between 30 and 40% people were bilingual in Wallonia (Walloon, Picard), among them 10% of the younger population (18–30 years old).

In 1572 Jean Bodin made a funny play on words which has been well known in Wallonia to the present: Ouallonnes enim a Belgis appelamur [nous, les "Gaulois"], quod Gallis veteribus contigit, quuum orbem terrarum peragrarent, ac mutuo interrogantes qaererent où allons-nous, id est quonam profiscimur?

ex eo credibile est Ouallones appellatos quod Latini sua lingua nunquam efferunt, sed g lettera utuntur.

[27]Translation: "We are called Walloons by the Belgians because when the ancient people of Gallia were travelling the length and breadth of the earth, it happened that they asked each other: 'Où allons-nous?'

It is probable they took from it the name Ouallons (Wallons), which the Latin speaking are not able to pronounce without changing the word by the use of the letter G." One of the best translations of his (humorous) sayings used daily in Wallonia[28] is "These are strange times we are living in."

A note in Henry VI, Part I says, "At this time, the Walloons [were] the inhabitants of the area, now in south Belgium, still known as the 'Pays wallon'.

The Belgian revolution was recently described as firstly a conflict between the Brussels municipality which was secondly disseminated in the rest of the country, "particularly in the Walloon provinces".

[34] We read the nearly same opinion in Edmundson's book: The royal forces, on the morning of September 23, entered the city at three gates and advanced as far as the Park.

But beyond that point they were unable to proceed, so desperate was the resistance, and such the hail of bullets that met them from barricades and from the windows and roofs of the houses.

The Provisional Government issued a series of decrees declaring Belgium independent, releasing the Belgian soldiers from their allegiance, and calling upon them to abandon the Dutch standard.

93–117), before writing "On the 6th October, the whole Wallonia is free",[38] he quotes the following municipalities from which volunteers were going to Brussels, the "centre of the commotion", in order to take part in the battle against the Dutch troops: Tournai, Namur, Wavre (p. 105) Braine-l'Alleud, Genappe, Jodoigne, Perwez, Rebecq, Grez-Doiceau, Limelette [fr], Nivelles (p. 106), Charleroi (and its region), Gosselies, Lodelinsart (p. 107), Soignies, Leuze, Thuin, Jemappes (p. 108), Dour, Saint-Ghislain, Pâturages [fr] (p. 109) and he concluded: "So, from the Walloon little towns and countryside, people came to the capital.."[39] The Dutch fortresses were liberated in Ath ( 27 September), Mons (29 September), Tournai (2 October), Namur (4 October) (with the help of people coming from Andenne, Fosses, Gembloux), Charleroi (5 October) (with people who came in their thousands).The same day that was also the case for Philippeville, Mariembourg, Dinant, Bouillon.

[40] In Flanders, the Dutch troops capitulated at the same time in Bruges, Ypres, Ostend, Menen, Oudenaarde, Geeraardsbergen (pp.

It is true that if you look at the birthplace of revolutionary given by the census, the number of Brussels falls to less than 60%, which could suggest that there was support "national" (to different provinces Belgian), or outside the city, more than 40%.But it is nothing, we know that between 1800 and 1830 the population of the capital grew by 75,000 to 103,000, this growth is due to the designation in 1815 in Brussels as a second capital of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the rural exodus that accompanied the Industrial Revolution.

As for Joseph Lebeau, he said that "patriotism Belgian is the son of the revolution of 1830.." Only in the following years as bourgeois revolutionary will "legitimize ideological state power.

[41]A few years after the Belgian revolution in 1830, the historian Louis Dewez underlined that "Belgium is shared into two people, Walloons and Flemings.

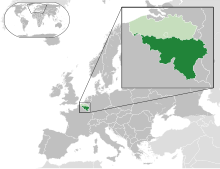

It is not an arbitrarian division or an imagined combination in order to support an opinion or create a system: it is a fact..."[42] Jules Michelet traveled in Wallonia in 1840 and mentions many times in his History of France his interest for Wallonia and the Walloons[43] (this page on the Culture of Wallonia), 476 (1851 edition published online)[44] The Walloon Region institutionally comprises also the German-speaking community of Belgium around Eupen, in the east of the region, next to Germany which ceded the area to Belgium after the First World War.

[45] Since the 11th century, the great towns along the river Meuse, for example, Dinant, Huy, and Liège, traded with Germany, where Wallengassen (Walloons' neighborhoods) were founded in certain cities.

[56] In the 13th century, the medieval German colonization of Transylvania, then part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now central and north-western Romania, also included numerous Walloons.

[57] Starting from the 1620s, numerous Walloon miners and iron-workers, with their families, settled in Sweden to work in iron mining and refining.

[59] They were originally led by the entrepreneur Louis de Geer, who commissioned them to work in the iron mines of Uppland and Östergötland.