Wandering Jew

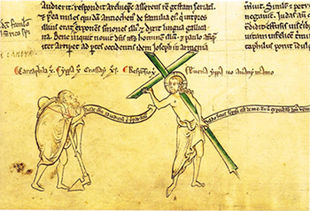

An early extant manuscript containing the legend is the Flores Historiarum by Roger of Wendover, where it appears in the part for the year 1228, under the title Of the Jew Joseph who is still alive awaiting the last coming of Christ.

[8] This name may have been chosen because the Book of Esther describes the Jews as a persecuted people, scattered across every province of Ahasuerus' vast empire, similar to the later Jewish diaspora in countries whose state and/or majority religions were forms of Christianity.

The name Paul Marrane (an anglicized version of Giovanni Paolo Marana, the alleged author of Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy) was incorrectly attributed to the Wandering Jew by a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article, yet the mistake influenced popular culture.

[11] The name Buttadeus (Botadeo in Italian; Boutedieu in French) most likely has its origin in a combination of the Vulgar Latin version of batuere ("to beat or strike") with the word for God, deus.

[12] The legend stems from Jesus' words given in Matthew 16:28: Ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν, εἰσίν τινες ὧδε ἑστῶτες, οἵτινες οὐ μὴ γεύσωνται θανάτου, ἕως ἂν ἴδωσιν τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐρχόμενον ἐν τῇ βασιλείᾳ αὐτοῦ.

[14] Extant manuscripts have shown that as early as the time of Tertullian (c. 200), some Christian proponents were likening the Jewish people to a "new Cain", asserting that they would be "fugitives and wanderers (upon) the earth".

In the entry for the year 1223, the chronicle describes the report of a group of pilgrims who meet "a certain Jew in Armenia" (quendam Iudaeum) who scolded Jesus on his way to be crucified and is therefore doomed to live until the Second Coming.

Matthew Paris included this passage from Roger of Wendover in his own history; and other Armenians appeared in 1252 at the Abbey of St Albans, repeating the same story, which was regarded there as a great proof of the truth of the Christian religion.

[23] Joseph Jacobs, writing in the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), commented, "It is difficult to tell in any one of these cases how far the story is an entire fiction and how far some ingenious impostor took advantage of the existence of the myth".

[24] The legend became more popular after it appeared in a 17th-century pamphlet of four leaves, Kurtze Beschreibung und Erzählung von einem Juden mit Namen Ahasverus (Short Description and Tale of a Jew with the Name Ahasuerus).

It is either the Ahasuerus of Klingemann or that of Achim von Arnim in his play, Halle and Jerusalem [de], to whom Richard Wagner refers in the final passage of his notorious essay Das Judenthum in der Musik.

The French writer Edgar Quinet published his prose epic on the legend in 1833, making the subject the judgment of the world; and Eugène Sue wrote his Juif errant in 1844, in which the author connects the story of Ahasuerus with that of Herodias.

One should also note Paul Féval, père's La Fille du Juif Errant (1864), which combines several fictional Wandering Jews, both heroic and evil, and Alexandre Dumas' incomplete Isaac Laquedem (1853), a sprawling historical saga.

[42] In Argentina, the topic of the Wandering Jew has appeared several times in the work of Enrique Anderson Imbert, particularly in his short-story El Grimorio (The Grimoire), included in the eponymous book.

Chapter XXXVII, "El Vagamundo", in the collection of short stories, Misteriosa Buenos Aires, by the Argentine writer Manuel Mujica Láinez also centres round the wandering of the Jew.

In Simone de Beauvoir's novel Tous les Hommes sont Mortels (All Men are Mortal, 1946), the leading figure Raymond Fosca undergoes a fate similar to the wandering Jew, who is explicitly mentioned as a reference.

Similarly, Mircea Eliade presents in his novel Dayan (1979) a student's mystic and fantastic journey through time and space under the guidance of the Wandering Jew, in the search of a higher truth and of his own self.

The Soviet satirists Ilya Ilf and Yevgeni Petrov had their hero Ostap Bender tell the story of the Wandering Jew's death at the hands of Ukrainian nationalists in The Little Golden Calf.

The novel Overburdened with Evil (1988) by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky involves a character in modern setting who turns out to be Ahasuerus, identified at the same time in a subplot with John the Divine.

In the novel Going to the Light (Идущий к свету, 1998) by Sergey Golosovsky, Ahasuerus turns out to be Apostle Paul, punished (together with Moses and Mohammed) for inventing false religion.

A quarter of a century later, the Wandering Jew takes on the guise of a gentile éminence grise who works out the genocidal ideology and bureaucracy of the Holocaust and secretly incites the Germans into carrying it out according to his plans.

George Sylvester Viereck and Paul Eldridge wrote a trilogy of novels My First Two Thousand Years: an Autobiography of the Wandering Jew (1928), in which Isaac Laquedem is a Roman soldier who, after being told by Jesus that he will "tarry until I return", goes on to influence many of the great events of history.

"Ahasver", a cult leader identified with the Wandering Jew, is a central figure in Anthony Boucher's classic mystery novel Nine Times Nine (originally published 1940 under the name H. Holmes).

features a highly influential character named Kane who is stated to have spawned the legends of the Walking Jew and the Flying Dutchman in his thousands of years maturing on Earth, guiding humanity toward the creation of technology which would allow it to return to its far-distant home in another solar system.

Jack L. Chalker wrote a five-book series called The Well World Saga in which it is mentioned many times that the creator of the universe, a man named Nathan Brazil, is known as the Wandering Jew.

The Wandering Jew is revealed to be Judas Iscariot in George R. R. Martin's distant-future science fiction parable of Christianity, the 1979 short story "The Way of Cross and Dragon".

In the first two novels of science fiction author Dan Simmons' Hyperion Cantos (1989-1997), a central character is referred to as the Wandering Jew as he roams the galaxy in search of a cure for his daughter's illness.

[14] Before Kaulbach's mural replica of his painting Titus destroying Jerusalem had been commissioned by the King of Prussia in 1842 for the projected Neues Museum, Berlin, Gabriel Riesser's essay "Stellung der Bekenner des mosaischen Glaubens in Deutschland" ("On the Position of Confessors of the Mosaic Faith in Germany") had been published in 1831 and the journal Der Jude, periodische Blätter für Religions und Gewissensfreiheit (The Jew, Periodical for Freedom of Religion and Thought) had been founded in 1832.

[66] A caricature which had first appeared in a French publication in 1852, depicting the legendary figure with "a red cross on his forehead, spindly legs and arms, huge nose and blowing hair, and staff in hand", was co-opted by anti-Semites.

[34] Glen Berger's 2001 play Underneath the Lintel is a monologue by a Dutch librarian who delves into the history of a book that is returned 113 years overdue and becomes convinced that the borrower was the Wandering Jew.