Waptia

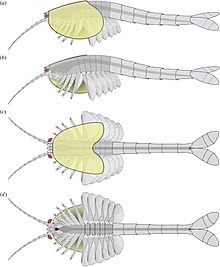

It grew to a length of 6.65 cm (3 in), and had a large bivalved carapace and a segmented body terminating into a pair of tail flaps.

Based on the number of individuals, Waptia fieldensis is the third most abundant arthropod from the Burgess Shale Formation, with thousands of specimens collected.

A comprehensive redescription published in 2018 classified it a member of Hymenocarina (which contains numerous other bivalved arthropods) within Mandibulata.

[1] The front of the head bore a pair of reniform (kidney shaped) compound eyes, about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) across, which were born on short stalks.

Similar structures are known from the related Canadaspis as well as other mandibulates, and are thought to correspond to the hemi-ellipsoid bodies of crustaceans, and thus likely have an olfactory function.

The front ends of each podomere bear setae (hair-like structures), which are orientated at an angle of 75° to 95° relative to the antennae axis.

[5] Specimens of Waptia fieldensis were recovered from the Burgess Shale Lagerstätte of Canada, which dates from the Middle Cambrian period (510 to 505 million years ago).

[5] Waptia was comprehensively redescribed in 2018, and was placed as part of the clade Hymenocarina within Mandibulata, closely related to Crustacea, due to the clear presence of mandibles and maxillae.

[1] In 1975, an apparently very similar species was described from the Lower Cambrian (515 to 520 million years ago) Maotianshan Shale Lagerstätte of Chengjiang, China.

In 1991, Hou Xian-guang and Jan Bergström reclassified it under the new genus Chuandianella when additional discoveries of more complete specimens made its resemblance to W. fieldensis more apparent.

[5][15] In 2022, Chuandianella was redescribed, and was shown to lack mandibles, thus it is probably not closely related to Waptia, despite its similar appearance.

[16] In 2002, a second similar species, Pauloterminus spinodorsalis, was recovered from the Lower Cambrian Sirius Passet Lagerstätte of the Buen Formation of northern Greenland.

However, the poor preservation of the P. spinodorsalis specimens, particularly of the appendages on the head, make it difficult to ascertain its taxonomic placement.

Phylogeny of Hymenocarina after Izquierdo-López and Caron (2024):[17]Tuzoia Perspicaris Pectocaris Loricicaris Tokummia Branchiocaris Plenocaris Ercaicunia Clypecaris Pauloterminus Canadaspis Waptia Chuandianella Vermontcaris Odaraia Jugatacaris Fibulacaris Pakucaris Balhuticaris Nereocaris While historically considered deposit feeders,[18] feeding by sifting through the sea bottom for edible organic particles,[3] the 2018 re-examination considered Waptia to have been an actively swimming predator of soft-bodied prey items, using its first three pairs of cephalothorax leg-like appendages to capture and manipulate prey, while moving its lamellated appendages in a rhythmic motion to propel itself through the water.

Along with Kunmingella douvillei and Chuandianella from the Chengjiang biota (around 7 million years older than the Burgess Shale) which also had fossilized eggs preserved inside the carapace, they constitute the oldest direct evidence of brood care and of K-selection among animals.