War and Peace

[4] The title may also be a reference to the Roman Emperor Titus, who reigned from 79 to 81 AD and was described as being a master of "war and peace" in The Twelve Caesars, written by Suetonius in 119.

The 1805 manuscript was re-edited and annotated in Russia in 1983 and has been since translated into English, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Albanian, Korean, and Czech.

His narrative structure is noted not only for its god's-eye point of view over and within events, but also in the way it swiftly and seamlessly portrayed an individual character's viewpoint.

[9] Tolstoy used a great deal of his own experience in the Crimean War to bring vivid detail and first-hand accounts of how the Imperial Russian Army was structured.

The novel begins in July 1805 in Saint Petersburg, at a soirée given by Anna Pavlovna Scherer, the maid of honour and confidante to the dowager empress Maria Feodorovna.

Educated abroad at his father's expense following his mother's death, Pierre is kindhearted but socially awkward, and finds it difficult to integrate into Petersburg society.

Andrei tells Pierre he has decided to become aide-de-camp to Prince Mikhail Ilarionovich Kutuzov in the coming war (the Battle of Austerlitz) against Napoleon in order to escape a life he cannot stand.

Bolkonsky, Rostov, and Denisov are involved in the disastrous Battle of Austerlitz, in which Prince Andrei is badly wounded as he attempts to rescue a Russian standard.

But his previous enthusiasm has been shattered; he no longer thinks much of Napoleon, "so petty did his hero with his paltry vanity and delight in victory appear, compared to that lofty, righteous and kindly sky which he had seen and comprehended".

Pierre Bezukhov, upon finally receiving his massive inheritance, is suddenly transformed from a bumbling young man into the most eligible bachelor in Russian society.

Burdened with nihilistic disillusionment, Prince Andrei does not return to the army but remains on his estate, working on a project that would codify military behavior to solve problems of disorganization responsible for the loss of life on the Russian side.

Prince Andrei feels impelled to take his newly written military notions to Saint Petersburg, naively expecting to influence either the Emperor himself or those close to him.

Young Natasha, also in Saint Petersburg, is caught up in the excitement of her first grand ball, where she meets Prince Andrei and briefly reinvigorates him with her vivacious charm.

Count Fyodor Rostopchin, the commander in chief of Moscow, is publishing posters, rousing the citizens to put their faith in religious icons, while at the same time urging them to fight with pitchforks if necessary.

After months of tribulation—during which the fever-plagued Karataev is shot by the French—Pierre is finally freed by a Russian raiding party led by Dolokhov and Denisov, after a small skirmish with the French that sees the young Petya Rostov killed in action.

He wrestles with the tension between our consciousness of freedom and the apparent need for necessity to develop laws of science and history, saying at times that the first is as real as the second, and yet that its reality would destroy the second.

He concludes that just as astronomy had to adopt the Copernican hypothesis of the earth's movement, not because it fits our immediate perceptions, but to avoid absurdities, so too must historical science accept some conception of necessary laws of human action, even though we feel free in our ordinary lives.

"[21] Writer and critic Nikolai Akhsharumov, writing in Vsemirny Trud (#6, 1867), suggested that War and Peace was "neither a chronicle, nor a historical novel", but a genre merger, this ambiguity never undermining its immense value.

"It is the [social] epic, the history novel and the vast picture of the whole nation's life," wrote Ivan Turgenev in his bid to define War and Peace in the foreword for his French translation of "The Two Hussars" (published in Paris by Le Temps in 1875).

[22] Articles by D. Minayev, Vasily Bervi-Flerovsky and N. Shelgunov in Delo magazine characterized the novel as "lacking realism", showing its characters as "cruel and rough", "mentally stoned", "morally depraved" and promoting "the philosophy of stagnation".

The critic praised Tolstoy's masterful portrayal of man at war, marveled at the complexity of the whole composition, organically merging historical facts and fiction.

"The dazzling side of the novel," according to Annenkov, was "the natural simplicity with which [the author] transports the worldly affairs and big social events down to the level of a character who witnesses them."

Still, being a true Slavophile, he could not fail to see the novel as promoting the major Slavophiliac ideas of "meek Russian character's supremacy over the rapacious European kind" (using Apollon Grigoryev's formula).

Ivan Goncharov in a July 17, 1878, letter to Pyotr Ganzen advised him to choose for translating into Danish War and Peace, adding: "This is positively what might be called a Russian Iliad.

[25] In 1879, unhappy with Ganzen having chosen Anna Karenina to start with, Goncharov insisted: "War and Peace is the extraordinary poem of a novel, both in content and execution.

"The objectivity and realism impart wonderful charm to all scenes, and alongside people of talent, honour and duty he exposes numerous scoundrels, worthless goons and fools," he added.

[28] In 1876 Dostoevsky wrote: "My strong conviction is that a writer of fiction has to have most profound knowledge—not only of the poetic side of his art, but also the reality he deals with, in its historical as well as contemporary context.

"[29] Nikolai Leskov, then an anonymous reviewer in Birzhevy Vestnik (The Stock Exchange Herald), wrote several articles praising highly War and Peace, calling it "the best ever Russian historical novel" and "the pride of the contemporary literature".

In his 1880 article written in the form of a letter addressed to Edmond Abou, the editor of the French newspaper Le XIXe Siècle, Turgenev described Tolstoy as "the most popular Russian writer" and War and Peace as "one of the most remarkable books of our age.

... She is faithful to the text and does not hesitate to render conscientiously those details that the uninitiated may find bewildering: for instance, the statement that Boris's mother pronounced his name with a stress on the o – an indication to the Russian reader of the old lady's affectation."

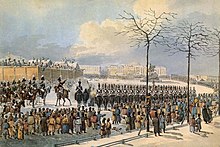

Painting by Louis-François Lejeune , 1822.