Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky

Sergey Mikhaylovich Prokudin-Gorsky (Russian: Сергей Михайлович Прокудин-Горский, IPA: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ prɐˈkudʲɪn ˈɡorskʲɪj] ⓘ; August 30 [O.S.

[1][2] Using a railway-car darkroom provided by Emperor Nicholas II, Prokudin-Gorsky travelled the Russian Empire from around 1909 to 1915 using his three-image colour photography to record its many aspects.

[4] Prokudin-Gorsky subsequently became the director of the executive board of Lavrov's metal works near Saint Petersburg and remained so until the October Revolution.

The following year, he travelled to Berlin and spent 6 weeks studying colour sensitization and three-colour photography with photochemistry professor Adolf Miethe, the most advanced practitioner in Germany at that time.

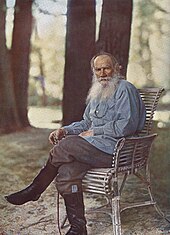

[8] Perhaps Prokudin-Gorsky's best-known work during his lifetime was his color portrait of Leo Tolstoy,[9] which was reproduced in various publications, on postcards, and as larger prints for framing.

In the 1930s, the elderly Prokudin-Gorsky continued with lectures showing his photographs of Russia to young Russians in France, but stopped commercial work and left the studio to his children, who named it Gorsky Frères.

[4] The method of color photography used by Prokudin-Gorsky was first suggested by James Clerk Maxwell in 1855 and demonstrated in 1861, but good results were not possible with the photographic materials available at that time.

His work gained attention in the 1890s when he exhibited color prints of various subjects such as oil and watercolor paintings, floral studies, and portraits from life.

[17] The first person to widely demonstrate good results by this method was Frederic E. Ives, whose "Kromskop" system of viewers, projectors and camera equipment was commercially available from 1897 until about 1907.

[7] Miethe was a photochemist who greatly improved the panchromatic characteristics of the black-and-white photographic materials suitable for use with this method of color photography.

He presented projected color photographs to the German Imperial Family in 1902 and was exhibiting them to the general public in 1903,[7] when they also began to appear in periodicals and books.

Some of the resulting images were published as postcards, featuring notable individuals including Kaiser Wilhelm II and Pope Pius X.

The other, more robust type was an essentially ordinary camera with a special sliding holder for the plates and filters that allowed each in turn to be efficiently shifted into position for exposure—an operation sometimes partly or even entirely automated with a pneumatic mechanism or spring-powered motor.

The most common model used a single oblong plate 9 cm wide by 24 cm high, the same format as Prokudin-Gorsky's surviving negatives, and it photographed the images in unconventional blue-green-red sequence, which is also a characteristic of Prokudin-Gorsky's negatives if the usual upside-down image in a camera and gravity-compliant downward shiftings of his plates are assumed.

[26] Autochrome plates were expensive and not sensitive enough for casual "snapshots" with a hand-held camera, but their use was simple and in expert hands they were capable of producing excellent results.

[27] Prokudin-Gorsky's own inventions, some of them collaborative, led to the granting of numerous patents, most issued during the years of his voluntary exile and not directly related to the body of work on which his fame now rests.

[28] Most of his patents relate to the production of natural-color motion pictures, a potentially lucrative application that attracted the attention of many inventors in the field of color photography during the 1910s and 1920s.

Around 1905, Prokudin-Gorsky envisioned and formulated a plan to use the emerging technological advances that had been made in color photography to document the Russian Empire systematically.

[32] By the time of Prokudin-Gorsky's death, the Tsar and his family had long since been executed during the Russian civil war, and most of the former empire was now the Soviet Union.

The surviving boxes of photo albums and fragile glass plates the negatives were recorded on were finally stored in the basement of a Parisian apartment building, and the family was worried about them getting damaged.

[35] Due to the very specialized and labor-intensive processes required to make photographic color prints from the negatives, only about a hundred of the images were used in exhibits, books and scholarly articles during the half-century after the Library of Congress acquired them.

[20] As the library offers the high-resolution images of the negatives freely on the Internet, many others have since created their own color representations of the photos,[48] and they have become a favorite testbed for computer scientists.