Warren County PCB Landfill

[1] In 1976, the United States Congress passed the Toxic Substances Control Act, which banned the production of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, effective January 1978 and regulated their disposal.

[2][3] In April the United States Environmental Protection Agency promulgated new regulations governing the disposal of various chemicals, including PCBs.

After Ward and Burns determined that the sandy soil at Bragg proved unsuitable for driving a truck and absorbing the fluid, they resolved to dispose of the rest of it in other rural areas.

[6] Through July and August, Burns and his sons dumped approximately 12,850 gallons of PCB-tainted fluid at 51 locations across 210 miles of roadway in 14 different North Carolina counties.

[5] Burns confessed to his role in the scheme and was arrested, while Ward was indicted by a federal grand jury and eventually convicted for eight counts of illegal disposal of PCBs in 1981.

[15] The announcement of the state's application of a permit for the construction of a PCB landfill in Warren County worried and angered local residents, who feared it would poison natural resources and damage the area's economy.

[17] Beginning with Governor Hunt's administration's December 20, 1978, announcement that "public sentiment would not deter the state from burying the PCBs in Warren County," the PCB landfill was surrounded by controversy.

The residence of the poor and predominantly African-American Warren County, North Carolina opposed the development there of a landfill designed to contain large quantities of soil contaminated with PCBs.

EPA and state officials claimed they could compensate for improper soil qualities and the close proximity to groundwater with the engineering design of their "state-of-the-art", "dry-tomb", zero-percent discharge landfill.

During this time it is said that citizens and some members of the working group urge Governor Hunt to clean up the dump and detoxify the PCB contaminated soil.

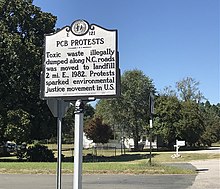

[19] After four years, Warren County citizens officially launched the environmental justice movement as they lay in front of 10,000 truckloads of contaminated PCB soil.

During the six-week trucking opposition, with collective nonviolent direct action, which included over 550 arrests, Warren County citizens mounted what the Duke Chronicle described as "the largest civil disobedience in the South since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., marched through Alabama.

With public pressure mounting, Governor Hunt then pledged to Warren citizens that when technology became available, the state would detoxify the PCB landfill.

[23] Soon after, academics and scholars began research and case studies to provide further evidence linking poor in minority neighborhoods across the country with a higher level of environmental hazards.

Decades after the initial incident the state of North Carolina was required to spend over $25 million to clean up and detoxify the Warren County PCBs landfill.