Water supply and sanitation in Vietnam

Among the challenges are continued widespread water pollution, poor service quality, low access to improved sanitation in rural areas, poor sustainability of rural water systems, insufficient cost recovery for urban sanitation, and the declining availability of foreign grant and soft loan funding as the Vietnamese economy grows and donors shift to loan financing.

[6][7][8] The government also promotes increased cost recovery through tariff revenues and has created autonomous water utilities at the provincial level, but the policy has had mixed success as tariff levels remain low and some utilities have engaged in activities outside their mandate.

Septic tanks are common, but with the exception of Hai Phong, no town offers a reasonable desludging service.

[3] The 7 million people in Ho Chi Minh City receive 93% of their drinking water from two treatment plants on the Dong Nai River and the much smaller Sai Gon River, with the remaining 7% coming from overexploited groundwater that is polluted by seawater intrusion and contamination.

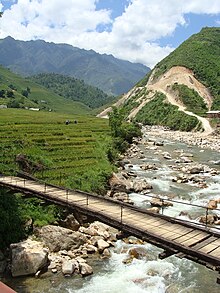

[15] A transmission pipeline from the existing plant on the Da River suffered numerous breaks, exacerbating water scarcity.

With anti-Chinese sentiment riding high in Vietnam, the faults have been blamed on the perceived low-cost Chinese technology behind the manufacturing process.

[16] In early 2009 tests by the Vietnam Institute of Biotechnology showed widespread contamination of municipal tap water, including high levels of e-coli.

[17] Ammonia in drinking water is not a direct health risk, but it can compromise disinfection efficiency, cause the failure of some filters, and it causes taste and odor problems.

[17] Water pollution is a serious issue in Vietnam as a result of rapid industrialization and urbanization without adequate environmental management.

Small enterprises engaged in food processing and textile dyeing in so-called "craft villages", of which there are 700 in the Red River Delta alone, discharge untreated wastewater.

8 industrial zones will be equipped with wastewater treatment plants with the help of a US$50 million loan from the World Bank approved in 2012.

In 2009 the government introduced the policy of “socialization” or “equitization” of water supply companies through Prime Minister Instruction 854/2009.

The policy is a byword for creating financially autonomous utilities that would ultimately be able to borrow from commercial banks.

[3] There is a National Strategy for Rural Clean Water Supply and Sanitation that was approved in 2000, which emphasizes a demand-responsive approach, meaning that users should take important decisions such as the most appropriate technology and the model of service provision.

[24] The Asian Development Bank concluded in 2010: "(the) government's intention to privatize water companies through the gradual process of equitization has not yet had the impact that may have been intended.

Private ownership of a share of the system assets was not backed up by clearly defined and verifiable performance indicators (...) The process to date has been characterized by a loss of management control, with no (short-term) benefit to either consumers or (potentially, in the long term) to the condition of the system's assets.

Instead, the equitization of water and wastewater companies is providing these companies with a Business License and a de facto authorization to grow outside their areas of core competence, posing a major threat to service delivery, due to a lack of proper regulation and control.

There may even be a disincentive for provinces to improve their monitoring systems, since it is in their interest to show that their access figures are low and that they are in need of more central funds.

Key decisions such as budgets, staff salary and benefits, and senior management appointments require approval by the provincial government.

In Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), a Malaysian firm has been operating the Binh An plant since 1994.

[27] The National Center for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation (CERWASS) and its provincial branch offices provides grant financing, requiring a user contribution, and organizes the construction of infrastructure.

[25] A World Bank study of rural water supply service delivery models in 2010 showed that there have been limited efforts to create the institutional framework necessary for sustainable service provision, that up to 90% of wells drilled are not operational and that "a large part of systems break down completely or need major repair within 3-4 years", partly due to poor quality construction.

[3] Between 1992 and 2002 about US$1 billion ($100 million per year) was invested in urban water supply and sanitation, out of which US$ 838m was financed by external donors.

A 1999 circular 03/1999 said that local government must gradually increase water tariffs to fully recover costs.

However, connection fees are high, especially in small towns, and – according to the World Bank - were “a major obstacle to achieving greater coverage of water supply services” in 2005.

In rural areas four smaller donor − Australia, Denmark, the UK and the Netherlands − have joined forces to provide budget support for a national program.

In 2010 the province of Soc Trang has been the first to enact a sewer tariff that is designed to recover the costs of operation and maintenance.

[33] One of them is the Red River Delta rural water supply and sanitation projects that promoted participatory approaches through the creation of joint-stock companies.

The loan proceeds will also be used to connect households west of the city along the transmission line from the Da River to Hanoi.

However, in 2016 the Hanoi People's Committee awarded a licence to build another water treatment plant on the Duong River west of the city in an area without a distribution network.