Gerridae

Consistent with the classification of the Gerridae as true bugs (i.e., suborder Heteroptera), gerrids have mouthparts evolved for piercing and sucking, and distinguish themselves by having the unusual ability to walk on water, making them pleuston (surface-living) animals.

The genus Halobates was first heavily studied between 1822 and 1883 when Francis Buchanan White collected several different species during the Challenger Expedition.

[3] Since then, the Gerridae have been continuously studied due to their ability to walk on water and unique social characteristics.

The family Gerridae is physically characterized by having hydrofuge hairpiles, retractable preapical claws, and elongated legs and body.

[8] Some water striders have wings present on the dorsal side of their thorax, while other species of Gerridae do not, particularly Halobates.

Water striders experience wing length polymorphism that has affected their flight ability and evolved in a phylogenetic manner where populations are either long-winged, wing-dimorphic, or short-winged.

[13] The ability for one brood to have young with wings and the next not allows water striders to adapt to changing environments.

Gerrids produce winged forms for dispersal purposes and macropterous individuals are maintained due to their ability to survive in changing conditions.

Ultimately, these switching mechanisms alter genetic alleles for wing characteristics, helping to maintain biological dispersal.

If the body of the water strider were to accidentally become submerged, for instance by a large wave, the tiny hairs would trap air.

The middle legs used for rowing have particularly well developed fringe hairs on the tibia and tarsus to help increase movement through the ability to thrust.

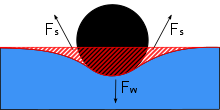

[4] The hind pair of legs are used for steering [16] When the rowing stroke begins, the middle tarsi of gerrids are quickly pressed down and backwards to create a circular surface wave in which the crest can be used to propel a forward thrust.

[4] The semicircular wave created is essential to the ability of the water strider to move rapidly since it acts as a counteracting force to push against.

[17] Gerrids generally lay their eggs on submerged rocks or vegetation using a gelatinous substance as a glue.

Each nymphal stage lasts 7–10 days and the water strider molts, shedding its old cuticle through a Y-shaped suture dorsal to the head and thorax.

[17] Nymphs are very similar to adults in behavior and diet, but are smaller (1 mm long), paler, and lack differentiation in tarsal and genital segments.

[17] Gerrids are aquatic predators and feed on invertebrates, mainly spiders and insects, that fall onto the water surface.

[20] Halobates, which are found on open sea, feed off floating insects, zooplankton, and occasionally resort to cannibalism of their own nymphs.

During the non-mating season when gerrids live in cooperative groups, and cannibalism rates are lower, water striders will openly share large kills with others around them.

Water strider cannibalism involves mainly hunting nymphs for mating territory and sometimes for food.

Water striders will move to areas of lower salt concentration, resulting in the mix of genes within brackish and freshwater bodies.

[17] Sex discrimination in some Gerridae species is determined through communication of ripple frequency produced on the water surface.

This is due to the large energy cost which would need to be spent to maintain their body temperature at functional levels.

These water striders have been found in leaf litter or under stationary shelters such as logs and rocks during the winter in seasonal areas.

[14] This reproductive diapause is a result of shortening day lengths during larval development and seasonal variation in lipid levels.

Without hunger playing a role, several studies have shown that neither Aquarius remigis nor Limnoporus dissortis parents preferentially cannibalize on non-kin.

[24] Young must disperse as soon as their wings are fully developed to avoid cannibalism and other territorial conflicts since neither parents nor siblings can identify members genetically related to themselves.

[14] During the mating season, gerrids will emit warning vibrations through the water and defend both their territory and the female in it.

Even though gerridae are very conspicuous, making their presence known through repel signals, they often live in large groups.

Instead of competing to reproduce, water striders can work together to obtain nutrition and shelter outside of the mating season.