Watercolor painting

Many Western artists, especially in the early 19th century, used watercolor primarily as a sketching tool in preparation for the "finished" work in oil or engraving.

[13] Watercolor art dates back to the cave paintings of paleolithic Europe[14] and has been used for manuscript illustration since at least Egyptian times, with particular prominence in the European Middle Ages.

Botanical artists have traditionally been some of the most exacting and accomplished watercolor painters, and even today, watercolors—with their unique ability to summarize, clarify, and idealize in full color—are used to illustrate scientific and museum publications.

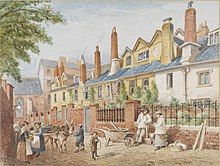

[20] Among the elite and aristocratic classes, watercolor painting was one of the incidental adornments of a good education; mapmakers, military officers, and engineers valued it for its usefulness in depicting properties, terrain,[21] fortifications, field geology, and for illustrating public works or commissioned projects.

Watercolor artists were commonly taken on geological or archaeological expeditions, funded by the Society of Dilettanti (founded in 1733), to document discoveries in the Mediterranean, Asia, and the New World.

These expeditions stimulated the demand for topographical painters, who churned out memento paintings of famous sites (and sights) along the Grand Tour to Italy that was undertaken by every fashionable young man of the time.

[22] In the late 18th century, the English cleric William Gilpin wrote a series of hugely popular books describing his picturesque journeys throughout rural England, and illustrated them with self-made sentimentalized monochrome watercolors of river valleys, ancient castles, and abandoned churches.

The confluence of these cultural, engineering, scientific, tourist, and amateur interests culminated in the celebration and promotion of watercolor as a distinctly English "national art".

William Blake published several books of hand-tinted engraved poetry, provided illustrations to Dante's Inferno, and he also experimented with large monotype works in watercolor.

His method of developing the watercolor painting in stages, starting with large, vague color areas established on wet paper, then refining the image through a sequence of washes and glazes,[33] permitted him to produce large numbers of paintings with "workshop efficiency"[34] and made him a multimillionaire, partly by sales from his personal art gallery, the first of its kind.

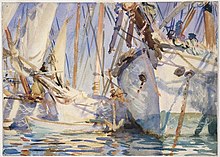

The late Georgian and Victorian periods produced the zenith of the British watercolor, among the most impressive 19th-century works on paper,[39] due to artists Turner, Varley, Cotman,[40] David Cox, Peter de Wint[41] William Henry Hunt, John Frederick Lewis,[42] Myles Birket Foster,[43] Frederick Walker,[44] Thomas Collier, Arthur Melville and many others.

In the 18th century, gouache was an important medium for the Italian artists Marco Ricci and Francesco Zuccarelli, whose landscape paintings were widely collected.

In the 19th century, the influence of the English school helped popularize "transparent" watercolor in France, and it became an important medium for Eugène Delacroix, François Marius Granet, Henri-Joseph Harpignies, and the satirist Honoré Daumier.

Among the many 20th-century artists who produced important works in watercolor were Wassily Kandinsky, Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, Egon Schiele, and Raoul Dufy.

The California painters exploited their state's varied geography, Mediterranean climate, and "automobility" to reinvigorate the outdoor or "plein air" tradition.

[55] Although the rise of abstract expressionism, and the trivializing influence of amateur painters and advertising- or workshop-influenced painting styles, led to a temporary decline in the popularity of watercolor painting after c. 1950,[56] watercolors continue to be utilized by artists like Martha Burchfield, Joseph Raffael, Andrew Wyeth, Philip Pearlstein,[57] Eric Fischl, Gerhard Richter, Anselm Kiefer, and Francesco Clemente.

In Spain, Ceferí Olivé created an innovative style followed by his students, such as Rafael Alonso López-Montero and Francesc Torné Gavaldà.

In the Canary Islands, where this pictorial technique has many followers, there are stand-out artists such as Francisco Bonnín Guerín, José Comas Quesada, and Alberto Manrique.

Watercolor painters before the turn of the 18th century had to make paints themselves using pigments purchased from an apothecary or specialized "colorman", and mixing them with gum arabic or some other binder.

The earliest commercial paints were small, resinous blocks that had to be wetted and laboriously "rubbed out" in water to obtain a usable color intensity.

[64] The majority of paints sold today are in collapsible small metal tubes in standard sizes and formulated to a consistency similar to toothpaste by being already mixed with a certain water component.

Paint manufacturers buy, by industrial standards very small, supplies of these pigments, mill them with the vehicle, solvent, and additives, and package them.

The milling process with inorganic pigments, in more expensive brands, reduces the particle size to improve the color flow when the paint is applied with water.

In fact, an important function of the gum is to facilitate the "lifting" (removal) of color, should the artist want to create a lighter spot in a painted area.