Tuff

They are the shattered walls of countless small bubbles that formed in the magma as dissolved gases rapidly came out of solution.

These fall to the surface as fallout deposits that are characteristically well-sorted and tend to form a blanket of uniform thickness across terrain.

[17] During welding, the glass shards and pumice fragments adhere together (necking at point contacts), deform, and compact together, resulting in a eutaxitic fabric.

[23] Tuffs have the potential to be deposited wherever explosive volcanism takes place, and so have a wide distribution in location and age.

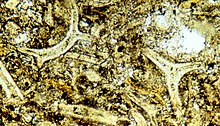

In the ancient rocks of Wales,[29] Charnwood,[30] etc., similar tuffs are known, but in all cases, they are greatly changed by silicification (which has filled them with opal, chalcedony, and quartz) and by devitrification.

[31] The frequent presence of rounded corroded quartz crystals, such as occur in rhyolitic lavas, helps to demonstrate their real nature.

[9] Welded ignimbrites can be highly voluminous, such as the Lava Creek Tuff erupted from Yellowstone Caldera in Wyoming 631,000 years ago.

In color, they are red or brown; their scoriae fragments are of all sizes from huge blocks down to minute granular dust.

The cavities are filled with many secondary minerals, such as calcite, chlorite, quartz, epidote, or chalcedony; in microscopic sections, though, the nature of the original lava can nearly always be made out from the shapes and properties of the little crystals which occur in the decomposed glassy base.

Even in the smallest details, these ancient tuffs have a complete resemblance to the modern ash beds of Cotopaxi, Krakatoa, and Mont Pelé.

[46] However, interaction between basaltic magma and groundwater or sea water results in hydromagmatic explosions that produce abundant ash.

The glassy basaltic ash produced in such eruptions rapidly alters to palagonite as part of the process of lithification.

They are black, dark green, or red in colour; vary greatly in coarseness, some being full of round spongy bombs a foot or more in diameter; and being often submarine, may contain shale, sandstone, grit, and other sedimentary material, and are occasionally fossiliferous.

When weathered, they are filled with calcite, chlorite, serpentine, and especially where the lavas contain nepheline or leucite, are often rich in zeolites, such as analcite, prehnite, natrolite, scolecite, chabazite, heulandite, etc.

[9] Ultramafic tuffs are extremely rare; their characteristic is the abundance of olivine or serpentine and the scarcity or absence of feldspar and quartz.

[49] Occurrences of ultramafic tuff include surface deposits of kimberlite at maars in the diamond-fields of southern Africa and other regions.

The principal variety of kimberlite is a dark bluish-green, serpentine-rich breccia (blue-ground) which, when thoroughly oxidized and weathered, becomes a friable brown or yellow mass (the "yellow-ground").

[9] These breccias were emplaced as gas–solid mixtures and are typically preserved and mined in diatremes that form intrusive pipe-like structures.

Because kimberlites are the most common igneous source of diamonds, the transitions from maar to diatreme to root-zone dikes have been studied in detail.

The "Schalsteins" of Devon and Germany include many cleaved and partly recrystallized ash-beds, some of which still retain their fragmental structure, though their lapilli are flattened and drawn out.

The more completely altered forms of these rocks are platy, green chloritic schists; in these, however, structures indicating their original volcanic nature only sparingly occur.

In the Eifel region of Germany, a trachytic, pumiceous tuff called trass has been extensively worked as a hydraulic mortar.

[9] Tuff of the Eifel region of Germany has been widely used for construction of railroad stations and other buildings in Frankfurt, Hamburg, and other large cities.

[56] The trade name Rochlitz Porphyr is the traditional designation for a dimension stone of Saxony with an architectural history over 1,000 years in Germany.

[59] Tuff from Rano Raraku was used by the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island to make the vast majority of their famous moai statues.

For example, dating of zircons in a metamorphosed tuff bed in the Pilar Formation provided some of the first evidence for the Picuris orogeny.