Jutland

Jutland's geography is flat, with comparatively steep hills in the east and a barely noticeable ridge running through the center.

The southwestern coast is characterised by the Wadden Sea, a large, unique international coastal region stretching through Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Jutland is known by several different names, depending on the language and era, including German: Jütland [ˈjyːtlant] ⓘ; Old English: Ēota land [ˈeːotɑˌlɑnd], known anciently as the Cimbric Peninsula or Cimbrian Peninsula (Latin: Cimbricus Chersonesus; Danish: den Cimbriske Halvø or den Jyske Halvø; German: Kimbrische Halbinsel or Jütische Halbinsel).

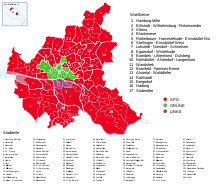

The peninsula's Kattegat and Baltic coastline stretches from Grenen down to the mouth of the Trave in Lübeck-Travemünde, and its Skagerrak and North Sea coastline runs from Grenen until down to the Geesthacht barrage east of Hamburg, which is defined as the point where the Lower Elbe (Unterelbe) and the estuary of the Elbe, that are subject to the tides, begin.

The bulk of the southernmost areas of the Jutland peninsula belongs to Holstein, stretching from the Elbe in the south to the Eider in the north.

One of the world's most frequented artificial waterways, the Kiel Canal, runs through the Jutland peninsula in Holstein, connecting the North Sea at Brunsbüttel to the Baltic at Kiel-Holtenau.

A system of Danish fortifications, the Danevirke, runs through Southern Schleswig, overcoming the drainage divide between Baltic (Schlei) and North Sea (Rheider Au).

The majority of what is today called Central Jutland is actually the traditional West Jutish culture and dialect area, i.e. Herning, Skive, Ikast, and Brande.

The largest Kattegat and Baltic islands off Jutland are Funen, Als, Læsø, Samsø, and Anholt in Denmark, as well as Fehmarn in Germany.

The islands of Læsø, Anholt, and Samsø in the Kattegat, and Als at the rim of the Baltic Sea, are administratively and historically tied to Jutland, although the latter two are also regarded as traditional districts of their own.

[citation needed] Many Angles, Saxons and Jutes migrated from Continental Europe to Great Britain starting around 450 AD.

The Kingdom of Kent in south east England is associated with Jutish origins and migration, also attributed by Bede in the Ecclesiastical History.

To protect themselves from invasion by the Christian Frankish emperors, beginning in the 5th century, the pagan Danes initiated the Danevirke, a defensive wall stretching from present-day Schleswig and inland halfway across the Jutland Peninsula.

Old Saxony was politically absorbed into the Carolingian Empire and Abodrites (or Obotrites), a group of Wendish Slavs who pledged allegiance to Charlemagne and who had for the most part converted to Christianity, were moved into the area to populate it.

This civic code covered the Danish part of the Jutland Peninsula, i.e., north of the Eider (river), Funen as well as Fehmarn.

[citation needed] During the industrialisation of the 1800s, Jutland experienced a large and accelerating urbanisation and many people from the countryside chose to emigrate.

Combined with falling grain prices on the international markets because of the Long Depression, and better opportunities in the cities due to an increasing industrialisation, many people in the countryside relocated to larger towns or emigrated.

Coastal areas of Jutland were declared a military zone where Danish citizens were required to carry identity cards, and access was regulated.

[citation needed] In December 1945, the remaining part of the German minority issued a declaration of loyalty to Denmark and democracy, renouncing any demands for a border revision.

[citation needed] The local culture of Jutland commoners before industrial times was not described in much detail by contemporary texts.

[12] While the peasantry of eastern Denmark was dominated by the upper feudal class, manifested in large estates owned by families of noble birth and an increasingly subdued class of peasant tenants, the farmers of Western Jutland were mostly free owners of their own land or leasing it from the Crown, although under frugal conditions.

[citation needed] When the industrialisation began in the 19th century, the social order was upheaved and with it the focus of the intelligentsia and the educated changed as well.

Søren Kierkegaard (1818–1855) grew up in Copenhagen as the son of a stern and religious West Jutlandic wool merchant who had worked his way up from a frugal childhood.

[12] Blicher was of Jutish origin and, soon after his pioneering work, many other writers followed with stories and tales set in Jutland and written in the homestead dialect.

Writer Evald Tang Kristensen (1843-1929) collected and published extensive accounts on the local rural Jutlandic folklore through many interviews and travels across the peninsula, including songs, legends, sayings and everyday life.

[citation needed] Peter Skautrup Centret at Aarhus University is dedicated to collect and archive information on Jutland culture and dialects from before the industrialisation.

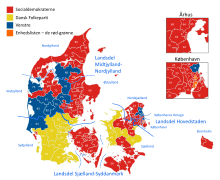

West Jutland is often claimed to have a mentality of self-sustainment, a superior work ethic and entrepreneurial spirit as well as slightly more religious and socially conservative values, and there are other voting patterns than in the rest of Denmark.

Musicians and entertainers Ib Grønbech[15][16][17][18] and Niels Hausgaard, both from Vendsyssel in Northern Jutland, use a distinct Jutish dialect.

[19] In the southernmost and northernmost parts of Jutland, there are associations striving to conserve their respective dialects, including the North Frisian language-speaking areas in Schleswig-Holstein.

Karsten Thomsen (1837–1889), an inn-keeper in Frøslev with artistic aspirations, wrote warmly about his homestead of South Jutland, using the dialect of his region explicitly.