Western Australian emergency of March 1944

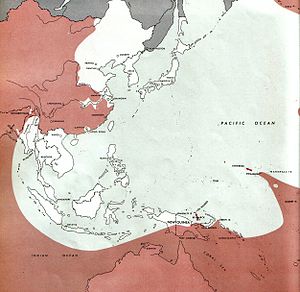

During March 1944, the Allies of World War II rapidly reinforced the military units located in the state of Western Australia to defend against the possibility that Japanese warships would attack the cities of Fremantle and Perth.

In February 1944, the Allies became alarmed that the movement of the main Japanese fleet to Singapore could be a precursor to raids in the Indian Ocean, including against Western Australia.

The emergency began when Allied code breakers detected the movement of a powerful force of Japanese warships in the Netherlands East Indies in early March.

After a United States Navy submarine made radar contact with two Japanese warships near one of the entrances to the Indian Ocean on 6 March, the Allied military authorities and Australian Government judged that a fleet may have been heading towards the Perth area.

Other Allied air units were held at Darwin in the Northern Territory to respond to raids on that town or reinforce Western Australia if the Japanese fleet was sighted.

[1] In February 1944, the Combined Fleet, the Imperial Japanese Navy's main striking force, withdrew from its base at Truk in the Central Pacific to Palau and Singapore.

The appearance of a powerful naval force at Singapore alarmed the Allies, as it was feared that these ships would conduct raids into the Indian Ocean and against Western Australia.

[12] Land-based aircraft were considered sufficient to counter any attacks on Fremantle and, on 28 February, General Headquarters directed Lieutenant General George Kenney, the commander of the Allied Air Forces, to prepare to: On 4 March, Curtin sent a cable to Churchill seeking the British Government's assessment of the likelihood of Japanese raids into the Indian Ocean, and the capacity of the Allied forces in the region to defeat any such attacks.

Curtin's cable crossed a message Churchill had sent the previous day, which stated that while Japanese forces could conduct raids against Allied shipping in the Indian Ocean, "it is not thought that serious danger, either to India or to Western Australia, is likely to develop".

[12] Although the Australian Government was reassured by Britain's assessment of the situation, the Allied military units stationed in Western Australia made preparations to resist a possible attack.

The Fremantle Fortress command, which was responsible for defending the port against naval bombardment or air attack, was placed on alert and ordered to station more heavy anti-aircraft guns near the city's docks.

Singapore had been selected as the Fleet's new base as it was close to sources of fuel and had suitable facilities to enable the ships to undertake training and maintenance before counter-attacking the Allies in the Pacific.

[15] In late February 1944, Vice-Admiral Shiro Takasu—the Commander in Chief of Japan's Southwest Area Fleet—ordered the heavy cruisers Aoba, Chikuma, and Tone to raid Allied shipping on the main route between Aden and Fremantle.

[17] The light cruisers Kinu and Ōi and three destroyers (which were designated a "Security and Supply Formation") escorted the raiding force through the Sunda Strait on 1 March.

[18][20] Nimitz was unsure whether to report this inconclusive contact, but decided to do so to prevent Fremantle from being subjected to a surprise attack; he later wrote that "'Remember Pearl Harbor' was the message that kept sticking in my mind".

[13][18] Also on 8 March, the commander of the Eastern Fleet, Admiral James Somerville, directed all Allied ships travelling in the Indian Ocean between 80 and 100° east to divert to the south or west.

Several US Navy submarines conducting patrols in the Indian Ocean and Netherlands East Indies were also directed to take up stations that would allow them to intercept Japanese ships bound for Fremantle, or attack such a force while it was returning to base.

Kenney also directed the United States Army Air Forces' heavy bomber-equipped 380th Bombardment Group to return from New Guinea to Fenton Airfield near Darwin, and be ready to move to Cunderdin or Geraldton if a threat to the Fremantle area developed.

[13] Air Commodore Raymond Brownell, the head of Western Area Command, disagreed with Bostock's decision to station three squadrons at Exmouth Gulf.

[26] The cyclone off the coast of Western Australia greatly hampered the flights, and led to concerns that the Japanese force could be approaching under the cover of bad weather.

Soldiers from the 104th Tank Attack Regiment manned anti-aircraft machine gun positions near the flying boat station in the Perth suburb of Crawley.

Acting upon advice from Brownell, the commanding officer of III Corps, Lieutenant General Gordon Bennett, ordered an air raid warning for Fremantle and Perth.

[18][26] The military authorities and government did not give any reason for the air raid alert until the next day, when the Western Australian minister with responsibility for civil defence, Alexander Panton, released a brief statement noting that the alarms had been sounded on legitimate grounds and the incident had not been a hoax.

[18] The 10th Light Horse Regiment established coast-watching positions, and an exercise practising the full activation of VDC-manned coastal and anti-aircraft defences on the night of 11/12 March was held.

[29] The units normally stationed in Western Australia returned to their usual locations and activities on 13 March, and the submarine tenders were escorted back to Fremantle by Adelaide.

[18] On 20 March, Kenney advised Bostock that the threat of attack had passed, and ordered that all the additional RAAF units sent to Western Australia return to their home bases.

[30] The Japanese raiders dispatched to the Indian Ocean encountered only a single Allied ship: on the morning of 9 March, Tone shelled and sank the British steamer Behar, which was bound from Fremantle to Colombo on a voyage to the United Kingdom.

After being attacked, the steamer's crew broadcast a distress signal to warn other Allied ships, causing the commander of the raiding force to abandon the operation.

[34] Allied concerns over the Combined Fleet's presence at Singapore eased considerably during March when it was learned that the ships there were being put through a maintenance program and that the Japanese did not intend to undertake major operations in the Indian Ocean area.

[38] The rationale for reinforcing Western Australia and the air raid alarms in March 1944 was not revealed by the Australian Government until 17 August 1945, two days after the end of the war.