White dwarf

A carbon–oxygen white dwarf which approaches this limit, typically by mass transfer from a companion star, may explode as a Type Ia supernova via a process known as carbon detonation;[1][5] SN 1006 is a likely example.

[11] In 1910, Henry Norris Russell, Edward Charles Pickering and Williamina Fleming discovered that, despite being a dim star, 40 Eridani B was of spectral type A, or white.

[35] Such densities are possible because white dwarf material is not composed of atoms joined by chemical bonds, but rather consists of a plasma of unbound nuclei and electrons.

[1] The existence of a limiting mass that no white dwarf can exceed without collapsing to a neutron star is another consequence of being supported by electron degeneracy pressure.

[44] This value was corrected by considering hydrostatic equilibrium for the density profile, and the presently known value of the limit was first published in 1931 by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in his paper "The Maximum Mass of Ideal White Dwarfs".

(Near the beginning of the 20th century, there was reason to believe that stars were composed chiefly of heavy elements,[44]: 955 so, in his 1931 paper, Chandrasekhar set the average molecular weight per electron, μe, equal to 2.5, giving a limit of 0.91 M☉.)

[51][52] In contrast, for a core primarily composed of oxygen, neon and magnesium, the collapsing white dwarf will typically form a neutron star.

Some calibrations are required to compensate for the gradual change in properties or different frequencies of abnormal luminosity supernovae at high redshift, and for small variations in brightness identified by light curve shape or spectrum.

If the star is allowed to rotate nonuniformly, and viscosity is neglected, then, as was pointed out by Fred Hoyle in 1947,[63] there is no limit to the mass for which it is possible for a model white dwarf to be in static equilibrium.

[66] The degenerate matter that makes up the bulk of a white dwarf has a very low opacity, because any absorption of a photon requires that an electron must transition to a higher empty state, which may not be possible as the energy of the photon may not be a match for the possible quantum states available to that electron, hence radiative heat transfer within a white dwarf is low; it does, however, have a high thermal conductivity.

A white dwarf remains visible for a long time, as its tenuous outer atmosphere slowly radiates the thermal content of the degenerate interior.

[29] As was explained by Leon Mestel in 1952, unless the white dwarf accretes matter from a companion star or other source, its radiation comes from its stored heat, which is not replenished.

[72][73]: §2.1 White dwarfs have an extremely small surface area to radiate this heat from, so they cool gradually, remaining hot for a long time.

The white dwarf luminosity function can therefore be used to find the time when stars started to form in a region; an estimate for the age of our galactic disk found in this way is 8 billion years.

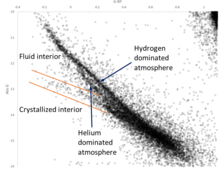

[87] As a white dwarf core undergoes crystallization into a solid phase, latent heat is released, which provides a source of thermal energy that delays its cooling.

[88] Another possible mechanism that was suggested to explain this cooling anomaly in some types of white dwarfs is a solid–liquid distillation process: the crystals formed in the core are buoyant and float up, thereby displacing heavier liquid downward, thus causing a net release of gravitational energy.

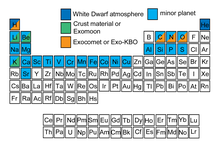

[95] Although most white dwarfs are thought to be composed of carbon and oxygen, spectroscopy typically shows that their emitted light comes from an atmosphere that is observed to be either hydrogen or helium dominated.

Likewise, a white dwarf with a polarized magnetic field, an effective temperature of 17000 K, and a spectrum dominated by He I lines that also had hydrogen features could be given the classification of DBAP3.

For example, a 2015 study of the white dwarf Ton 345 concluded that its metal abundances were consistent with those of a differentiated, rocky planet whose mantle had been eroded by the host star's wind during its asymptotic giant branch phase.

If these theories are not valid, the proton might still decay by complicated nuclear reactions or through quantum gravitational processes involving virtual black holes; in these cases, the lifetime is estimated to be no more than 10200 years.

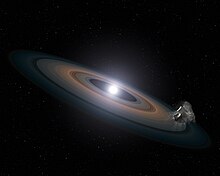

[156] A less common observable evidence is infrared excess due to a flat and optically thick debris disk, which is found in around 1%–4% of white dwarfs.

[160] White dwarfs hotter than 27000 K sublimate all the dust formed by tidally disrupting a rocky body, preventing the formation of a debris disk.

[162][163] Infrared spectroscopic observations made by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope of the central star of the Helix Nebula suggest the presence of a dust cloud, which may be caused by cometary collisions.

[186] A search has been proposed for transits of hypothetical Earth-like planets around white dwarfs with surface temperatures of less than 10000 K. Such stars that could harbor a habitable zone at a distance of c. 0.005 to 0.02 AU that would last upwards of 3 billion years.

[187] Newer research casts some doubts on this idea, given that the close orbits of those hypothetical planets around their parent stars would subject them to strong tidal forces that could render them uninhabitable by triggering a greenhouse effect.

[189] If a white dwarf is in a binary star system and is accreting matter from its companion, a variety of phenomena may occur, including novae and Type Ia supernovae.

[191] A close binary system of two white dwarfs can lose angular momentum and radiate energy in the form of gravitational waves, causing their mutual orbit to steadily shrink until the stars merge.

As their mass approaches the Chandrasekhar limit, this could theoretically lead to either the explosive ignition of fusion in the white dwarf or its collapse into a neutron star.

[1][195][196] In another possible mechanism for Type Ia supernovae, the double-degenerate model, two carbon–oxygen white dwarfs in a binary system merge, creating an object with mass greater than the Chandrasekhar limit in which carbon fusion is then ignited.

As a white dwarf accretes material quickly, the core can ignite off-center, which leads to gravitational instabilities that could create a neutron star.