Whitewater

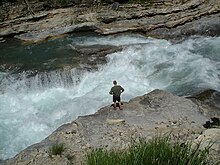

Whitewater forms in the context of rapids, in particular, when a river's gradient changes enough to generate so much turbulence that air is trapped within the water.

The term "whitewater" also has a broader meaning, applying to any river or creek that has a significant number of rapids.

[1] Four factors, separately or in combination, can create rapids: gradient, constriction, obstruction, and flow rate.

Streambed topography is the primary factor in creating rapids, and is generally consistent over time.

This loss determines the river's slope, and to a large extent its rate of flow (velocity).

This pressure causes the water to flow more rapidly and to react to riverbed events (rocks, drops, etc.).

[citation needed] In large rivers with high flow rates next to an obstruction, "eddy walls" can occur.

(In many cases, a lower rated rapid may give a better "ride" to kayakers or rafters, while a Class V may seem relatively tame.

A rapid's grade is not fixed, since it may vary greatly depending on the water depth and speed of flow.

At flood stage, even rapids that are usually easy can contain lethal and unpredictable hazards (briefly adapted from the American version[3] of the International Scale of River Difficulty).

On any given rapid, a multitude of different features can arise from the interplay between the shape of the riverbed and the velocity of the water in the stream.

For a person caught in this position, getting to safety will be difficult or impossible, often leading to a fatal outcome.

Strainers are formed by many natural or man-made objects, such as storm grates over tunnels, trees that have fallen into a river ("log jam"), bushes by the side of the river that are flooded during high water, wire fence, rebar from broken concrete structures in the water, or other debris.

Sweepers are trees fallen in or heavily leaning over the river, still rooted on the shore and not fully submerged.

In a low-head dam, the 'hole' has a very wide, uniform structure with no escape point, and the sides of the hydraulic (ends of the dam) are often blocked by a man-made wall, making paddling around, or slipping off, the side of the hydraulic, where the bypass water flow would become normal (laminar), difficult.

By (upside-down) analogy, this would be much like a surfer slipping out the end of the pipeline, where the wave no longer breaks.

Typically, they are calm spots where the downward movement of water is partially or fully arrested—a place to rest or to make one's way upstream.

Often containing boils and whirlpools, eddy lines can spin and grab your watercraft in unexpected ways, but if used correctly, they can be a really playful spot.

Undercut rocks have been worn down underneath the surface by the river, or are loose boulders which cantilever out beyond their resting spots on the riverbed.

[5] [6] Another major whitewater feature is a sieve, which is a narrow, empty space through which water flows between two obstructions, usually rocks.

People use many types of whitewater craft to make their way down a rapid, preferably with finesse and control.

They are often shorter and more maneuverable than sea kayaks and are specially designed to deal with water flowing up onto their decks.

The design is characterized by a wide, flat bottom, flared sides, a narrow, flat bow, a pointed stern, and extreme rocker in the bow and stern to allow the boat to spin about its center for ease in maneuvering in rapids.

River bugs are small, single-person, inflatable craft where a person's feet stick out of one end.

The boards are typically specially designed for whitewater use, and more safety gear is used than on flat water.

Fatalities do occur; some 50 people die in whitewater accidents in the United States each year.

Scouting or examining the rapids before running them is crucial to familiarize oneself with the stream and anticipate the challenges.