1975 Australian constitutional crisis

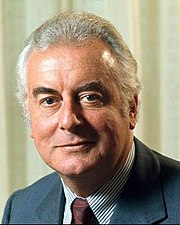

In May 1974, after the Senate voted to reject six of Labor's non-supply bills, Whitlam advised governor-general Sir Paul Hasluck to call a double dissolution election.

In both instances where those circumstances arose prior to the Whitlam government, in 1914 and 1951, the governor-general dissolved Parliament for a double dissolution election on the recommendation of the prime minister.

[15] In April 1974, faced with attempts by the Opposition under Billy Snedden to block supply (appropriation bills) in the Senate, Whitlam obtained the concurrence of the governor-general, Sir Paul Hasluck, to a double dissolution.

[17] Snedden later told author Graham Freudenberg when being interviewed for the book A Certain Grandeur – Gough Whitlam in Politics: "The pressure [to block supply] was on me from Anthony.

[30] Whitlam's original deputy prime minister, Lance Barnard, had been challenged and defeated for his post by Cairns in June 1974 shortly after the May 1974 election.

[33] The next week, Whitlam fired Cairns for misleading Parliament regarding the Loans Affair amid innuendo about his relationship with his Principal Private Secretary, Junie Morosi.

[35] Queensland Country Party Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen had evidence that Colston, a schoolteacher by trade, had set a school on fire during a labour dispute, though the police had refused to prosecute.

[35] Whitlam argued that because of the vacancies being filled as they were, the Senate was "corrupted" and "tainted", with the Opposition enjoying a majority they did not win at the ballot box.

[37] When Labor learned that Field had not given the required three weeks notice to the Queensland Department of Education, it challenged his appointment in the High Court, arguing that he was still technically a public servant–and thus ineligible to serve in the Senate.

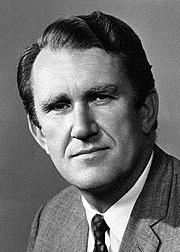

[41] In the wake of the High Court ruling, and with the appropriation bills due to be considered by the Senate on 16 October, Fraser was undecided whether to block supply.

Ellicott indicated that Whitlam was treating Kerr as if he had no discretion but to follow prime ministerial advice, when in fact the Governor-General could and should dismiss a ministry unable to secure supply.

[54] Kerr rang Whitlam on Sunday 19 October, asking permission to consult with the Chief Justice of the High Court, Sir Garfield Barwick, concerning the crisis.

Whitlam advised Kerr not to do so, noting that no Governor-General had consulted with a Chief Justice under similar circumstances since 1914, when Australia was at a much earlier stage of her constitutional development.

[9] Kerr invited Whitlam and Minister for Labour Senator Jim McClelland to lunch on 30 October, immediately preceding an Executive Council meeting.

If the Opposition were to allow supply to pass, Whitlam would not advise a half-Senate election until May or June 1976, and the Senate would not convene until 1 July, thus obviating the threat of a possible temporary Labor majority.

Both men were busy in the morning, Kerr with Remembrance Day commemorations, and Whitlam with a caucus meeting and a censure motion in the House which the Opposition had submitted.

According to Kerr, he interrupted Whitlam and asked if, as a result of the failure to find a compromise between party leaders, he intended to govern without parliamentary supply, to which the Prime Minister answered, "Yes".

[82] Fraser left to return to Parliament House, where he conferred with Coalition leaders, while Kerr joined the luncheon party that had been waiting for him, apologising to his guests and offering the excuse that he had been busy dismissing the Government.

Authoritative word did not reach Wriedt until 2.15 pm, by which time it was too late to withdraw the motion and instead obstruct his party's appropriation bill to hinder Fraser.

Fraser's new government suffered repeated defeats in the House, which passed a motion of no confidence in him, and asked the Speaker, Gordon Scholes, to urge the Governor-General to recommission Whitlam.

[93] Kerr's action was based on the advice he had received from two High Court judges (Mason and Chief Justice Barwick) and the Crown Law Officers (Byers and Clarence Harders, the Secretary of the Attorney-General's Department).

The dismissal was by then publicly known, and an angry crowd of ALP supporters had gathered, filling the steps and spilling over both into the roadway and into Parliament House itself.

The Proclamation which you have just heard read by the Governor-General's Official Secretary was countersigned Malcolm Fraser, who will undoubtedly go down in Australian history from Remembrance Day 1975 as Kerr's cur.

The Coalition attacked Labor for the economic conditions, and released television commercials "The Three Dark Years" showing images from the Whitlam government scandals.

[110] There was little violence in the campaign, but three letter bombs were placed in the post; one wounded two people in Bjelke-Petersen's office, while the other two, addressed to Kerr and Fraser, were intercepted and defused.

[112] In the 13 December election, the Coalition won a record victory, with 91 seats in the House of Representatives to the ALP's 36 and a 35–27 majority in the expanded Senate.

When Kerr announced his resignation as governor-general on 14 July 1977, Whitlam commented: "How fitting that the last of the Bourbons should bow out on Bastille Day".

[129] According to Whitlam speechwriter Graham Freudenberg, "the residual rage over the conduct of the Queen's representative found a constructive outlet in the movement for the Australian Republic".

According to Kerr, Charles had responded: "But surely, Sir John, the Queen should not have to accept advice that you should be recalled at the very time when you were considering having to dismiss the government".

[140] Beginning in 2012, Hocking attempted to gain the release of correspondence between the Queen's advisors and Kerr regarding the dismissal, held by the National Archives.