Norbert Wiener

His work heavily influenced computer pioneer John von Neumann, information theorist Claude Shannon, anthropologists Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, and others.

Earning his living teaching German and Slavic languages, Leo read widely and accumulated a personal library from which the young Norbert benefited greatly.

"[8] He graduated from Ayer High School in 1906 at 11 years of age, and Wiener then entered Tufts College.

Back at Harvard, Wiener became influenced by Edward Vermilye Huntington, whose mathematical interests ranged from axiomatic foundations to engineering problems.

Harvard awarded Wiener a PhD in June 1913, when he was only 19 years old, for a dissertation on mathematical logic (a comparison of the work of Ernst Schröder with that of Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell), supervised by Karl Schmidt, the essential results of which were published as Wiener (1914).

Wiener was briefly a journalist for the Boston Herald, where he wrote a feature story on the poor labor conditions for mill workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, but he was fired soon afterwards for his reluctance to write favorable articles about a politician the newspaper's owners sought to promote.

In 1916, with America's entry into the war drawing closer, Wiener attended a training camp for potential military officers but failed to earn a commission.

In the summer of 1918, Oswald Veblen invited Wiener to work on ballistics at the Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.

However, Wiener was still eager to serve in uniform and decided to make one more attempt to enlist, this time as a common soldier.

Wiener wrote in a letter to his parents, "I should consider myself a pretty cheap kind of a swine if I were willing to be an officer but unwilling to be a soldier.

"[12] This time the army accepted Wiener into its ranks and assigned him, by coincidence, to a unit stationed at Aberdeen, Maryland.

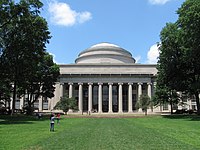

At W. F. Osgood's suggestion, Wiener was hired as an instructor of mathematics at MIT, where, after his promotion to professor, he spent the remainder of his career.

He spent most of his time at Göttingen and with Hardy at Cambridge, working on Brownian motion, the Fourier integral, Dirichlet's problem, harmonic analysis, and the Tauberian theorems.

(The now-standard practice of modeling an information source as a random process—in other words, as a variety of noise—is due to Wiener.)

Initially his anti-aircraft work led him to write, with Arturo Rosenblueth and Julian Bigelow, the 1943 article 'Behavior, Purpose and Teleology', which was published in Philosophy of Science.

[23] Patrick D. Wall speculated that after the publication of Cybernetics, Wiener asked McCulloch for some physiological facts about the brain that he could then theorize.

After the war, Wiener became increasingly concerned with what he believed was political interference with scientific research, and the militarization of science.

In 1926 Wiener married Margaret Engemann, an assistant professor of modern languages at Juniata College.

It was Wiener's idea to model a signal as if it were an exotic type of noise, giving it a sound mathematical basis.

[34] Wiener is one of the key originators of cybernetics, a formalization of the notion of feedback, with many implications for engineering, systems control, computer science, biology, philosophy, and the organization of society.

Wiener developed the filter at the Radiation Laboratory at MIT to predict the position of German bombers from radar reflections.

Specifically, a nonlinear system can be identified by inputting a white noise process and computing the Hermite-Laguerre expansion of its output.

[38][39] Wiener took a great interest in the mathematical theory of Brownian motion (named after Robert Brown) proving many results now widely known, such as the non-differentiability of the paths.

The Paley–Wiener theorem relates growth properties of entire functions on Cn and Fourier transformation of Schwartz distributions of compact support.