Brownian motion

[citation needed] This motion is named after the Scottish botanist Robert Brown, who first described the phenomenon in 1827, while looking through a microscope at pollen of the plant Clarkia pulchella immersed in water.

In 1900, the French mathematician Louis Bachelier modeled the stochastic process now called Brownian motion in his doctoral thesis, The Theory of Speculation (Théorie de la spéculation), prepared under the supervision of Henri Poincaré.

Then, in 1905, theoretical physicist Albert Einstein published a paper where he modeled the motion of the pollen particles as being moved by individual water molecules, making one of his first major scientific contributions.

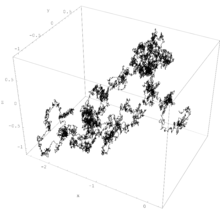

[3] The direction of the force of atomic bombardment is constantly changing, and at different times the particle is hit more on one side than another, leading to the seemingly random nature of the motion.

This explanation of Brownian motion served as convincing evidence that atoms and molecules exist and was further verified experimentally by Jean Perrin in 1908.

There exist sequences of both simpler and more complicated stochastic processes which converge (in the limit) to Brownian motion (see random walk and Donsker's theorem).

[6][7] The Roman philosopher-poet Lucretius' scientific poem "On the Nature of Things" (c. 60 BC) has a remarkable description of the motion of dust particles in verses 113–140 from Book II.

He uses this as a proof of the existence of atoms: Observe what happens when sunbeams are admitted into a building and shed light on its shadowy places.

So the movement mounts up from the atoms and gradually emerges to the level of our senses so that those bodies are in motion that we see in sunbeams, moved by blows that remain invisible.Although the mingling, tumbling motion of dust particles is caused largely by air currents, the glittering, jiggling motion of small dust particles is caused chiefly by true Brownian dynamics; Lucretius "perfectly describes and explains the Brownian movement by a wrong example".

[9] While Jan Ingenhousz described the irregular motion of coal dust particles on the surface of alcohol in 1785, the discovery of this phenomenon is often credited to the botanist Robert Brown in 1827.

The first person to describe the mathematics behind Brownian motion was Thorvald N. Thiele in a paper on the method of least squares published in 1880.

This was followed independently by Louis Bachelier in 1900 in his PhD thesis "The theory of speculation", in which he presented a stochastic analysis of the stock and option markets.

The Brownian model of financial markets is often cited, but Benoit Mandelbrot rejected its applicability to stock price movements in part because these are discontinuous.

[10] Albert Einstein (in one of his 1905 papers) and Marian Smoluchowski (1906) brought the solution of the problem to the attention of physicists, and presented it as a way to indirectly confirm the existence of atoms and molecules.

Their equations describing Brownian motion were subsequently verified by the experimental work of Jean Baptiste Perrin in 1908.

In 2010, the instantaneous velocity of a Brownian particle (a glass microsphere trapped in air with optical tweezers) was measured successfully.

[3] Classical mechanics is unable to determine this distance because of the enormous number of bombardments a Brownian particle will undergo, roughly of the order of 1014 collisions per second.

in a one-dimensional (x) space (with the coordinates chosen so that the origin lies at the initial position of the particle) as a random variable (

From this expression Einstein argued that the displacement of a Brownian particle is not proportional to the elapsed time, but rather to its square root.

[14] The second part of Einstein's theory relates the diffusion constant to physically measurable quantities, such as the mean squared displacement of a particle in a given time interval.

Gravity tends to make the particles settle, whereas diffusion acts to homogenize them, driving them into regions of smaller concentration.

It had been pointed out previously by J. J. Thomson[15] in his series of lectures at Yale University in May 1903 that the dynamic equilibrium between the velocity generated by a concentration gradient given by Fick's law and the velocity due to the variation of the partial pressure caused when ions are set in motion "gives us a method of determining Avogadro's constant which is independent of any hypothesis as to the shape or size of molecules, or of the way in which they act upon each other".

Introducing the ideal gas law per unit volume for the osmotic pressure, the formula becomes identical to that of Einstein's.

However, when he relates it to a particle of mass m moving at a velocity u which is the result of a frictional force governed by Stokes's law, he finds

Thus, even though there are equal probabilities for forward and backward collisions there will be a net tendency to keep the Brownian particle in motion, just as the ballot theorem predicts.

These orders of magnitude are not exact because they don't take into consideration the velocity of the Brownian particle, U, which depends on the collisions that tend to accelerate and decelerate it.

and V.[25] The Brownian velocity of Sgr A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy, is predicted from this formula to be less than 1 km s−1.

[30] The French mathematician Paul Lévy proved the following theorem, which gives a necessary and sufficient condition for a continuous Rn-valued stochastic process X to actually be n-dimensional Brownian motion.

Let X = (X1, ..., Xn) be a continuous stochastic process on a probability space (Ω, Σ, P) taking values in Rn.

The narrow escape problem is a ubiquitous problem in biology, biophysics and cellular biology which has the following formulation: a Brownian particle (ion, molecule, or protein) is confined to a bounded domain (a compartment or a cell) by a reflecting boundary, except for a small window through which it can escape.