Wife selling (English custom)

At least one early 19th-century magistrate is on record as stating that he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husbands to sell their wives, rather than having to maintain the family in workhouses.

In one of the last reported instances of a wife sale in England, a woman giving evidence in a Leeds police court in 1913 claimed that she had been sold to one of her husband's workmates for £1.

[2] The practice was common enough in the 17th century for the English philosopher John Locke to write (apparently as a joke) in a letter to French scientist Nicolas Toinard [fr] that "Among other things I have ordered you a beautiful girl to be your wife ...

One was to sue in the ecclesiastical courts for separation from bed and board (a mensa et thoro), on the grounds of adultery or life-threatening cruelty, but it did not allow a remarriage.

[20] The Duke of Chandos, while staying at a small country inn, saw the ostler beating his wife in a most cruel manner; he interfered and literally bought her for half a crown.

On her death-bed, she had her whole household assembled, told them her history, and drew from it a touching moral of reliance on Providence; as from the most wretched situation, she had been suddenly raised to one of the greatest prosperity; she entreated their forgiveness if at any time she had given needless offence, and then dismissed them with gifts; dying almost in the very act.

In 1696, Thomas Heath Maultster was fined for "cohabiteing in an unlawful manner with the wife of George ffuller of Chinner ... haueing bought her of her husband at 2d.q.

[23] In an Oxford case of 1789 wife selling is described as "the vulgar form of Divorce lately adopted", suggesting that even if it was by then established in some parts of the country it was only slowly spreading to others.

[26] Often the purchaser was arranged in advance, and the sale was a form of symbolic separation and remarriage, as in a case from Maidstone, where in January 1815 John Osborne planned to sell his wife at the local market.

However, as no market was held that day, the sale took place instead at "the sign of 'The Coal-barge,' in Earl Street", where "in a very regular manner", his wife and child were sold for £1 to a man named William Serjeant.

At another sale in September 1815, at Staines market, "only three shillings and four pence were offered for the lot, no one choosing to contend with the bidder, for the fair object, whose merits could only be appreciated by those who knew them.

[33] It was believed during the mid-19th century that wife selling was restricted to the lowest levels of labourers, especially to those living in remote rural areas, but an analysis of the occupations of husbands and purchasers reveals that the custom was strongest in "proto-industrial" communities.

[36] According to authors Wade Mansell and Belinda Meteyard, money seems usually to have been a secondary consideration;[4] the more important factor was that the sale was seen by many as legally binding, despite it having no basis in law.

Entries have been found in baptismal registers, such as this example from Perleigh in Essex, dated 1782: "Amie Daughter of Moses Stebbing by a bought wife delivered to him in a Halter".

[37][39]In some cases, such as that of Henry Cook in 1814, the Poor Law authorities forced the husband to sell his wife rather than have to maintain her and her child in the Effingham workhouse.

In 1735, a successful wife sale in St Clements was announced by the common cryer,[c] who wandered the streets ensuring that local traders were aware of the former husband's intention not to honour "any debts she should contract".

A sale a century earlier in Brighton involved "eight pots of beer" and seven shillings (£40 in 2025);[35] and in Ninfield in 1790, a man who swapped his wife at the village inn for half a pint of gin changed his mind and bought her back later.

[45] In his account, Wives for Sale, author Samuel Pyeatt Menefee collected 387 incidents of wife selling, the last of which occurred in the early 20th century.

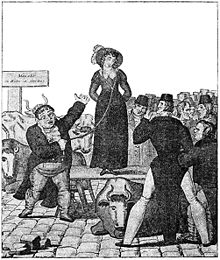

Sales often took place at fairs, in front of public houses, or local landmarks such as the obelisk at Preston (1817), or Bolton's "gas pillar"[f] (1835), where crowds could be expected to gather.

[50] Along with other English customs, settlers arriving in the American colonies during the late 17th and early 18th centuries took with them the practice of wife selling, and the belief in its legitimacy as a way of ending a marriage.

He was given the outstanding sum by two generous bystanders, and paid the husband—who promptly "gave the Woman a modest Salute wishing her well, and his Brother Sterling much Joy of his Bargain.

[52] On Friday a butcher exposed his wife to Sale in Smithfield Market, near the Ram Inn, with a halter about her neck, and one about her waist, which tied her to a railing, when a hog-driver was the happy purchaser, who gave the husband three guineas and a crown for his departed rib.

[54] When a labourer offered his wife for sale on Smithfield market in 1806, "the public became incensed at the husband, and would have severely punished him for his brutality, but for the interference of some officers of the police.

[38] JPs in Quarter Sessions became more active in punishing those involved in wife selling, and some test cases in the central law courts confirmed the illegality of the practice.

[55] Newspaper accounts were often disparaging: "a most disgusting and disgraceful scene" was the description in a report of 1832,[56] but it was not until the 1840s that the number of cases of wife selling began to decline significantly.

[45] Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, considered wife sales to be a conspiracy to commit adultery, but few of those reported in the newspapers led to prosecutions in court.

[57] In 1825 a man named Johnson was charged with "having sung a song in the streets describing the merits of his wife, for the purpose of selling her to the highest bidder at Smithfield."

[g][59] The arresting officer claimed that the man had gathered a "crowd of all sorts of vagabonds together, who appeared to listen to his ditty, but were in fact, collected to pick pockets."

The defendant, however, replied that he had "not the most distant idea of selling his wife, who was, poor creature, at home with her hungry children, while he was endeavouring to earn a bit of bread for them by the strength of his lungs."

"[64]Such complaints were still commonplace nearly 20 years later; in The Book of Days (1864), author Robert Chambers wrote about a case of wife selling in 1832, and noted that: {{quote:"the occasional instances of wife-sale, while remarked by ourselves with little beyond a passing smile, have made a deep impression on our continental neighbours, [who] constantly cite it as an evidence of our low civilisation.