Wilbur Olin Atwater

Afterwards, he continued his education for the next two years in Leipzig and Berlin, studying physiological chemistry and acquainting himself with the agricultural experiment stations of Europe.

[7] Atwater spent time traveling throughout Scotland, Rome, and Naples; on his trip he wrote articles about his observations for local newspapers based in the places he had lived in the United States.

[9] Both he, and his mentor from Yale, Samuel Johnson, were proponents of bringing organizations to the United States similar to the agricultural experiment stations they saw in Europe.

[12] To persuade the Connecticut legislature to appropriate money for a station, Orange Judd donated funds and Wesleyan offered laboratory facilities and Atwater's services on a part-time basis.

[8] Through their work and a $5,600 contribution from the Connecticut legislature for a two-year trial period, the first agricultural experiment station was created in the United States.

[3][5] Many of his articles appeared in a column called "Science Applied to Farming", mostly discussing agricultural fertilizers in Orange Judd's American Agriculturalist.

From 1879 to 1882, he conducted extensive human food studies on behalf of the United States Fish Commission and Smithsonian Institution.

[6] For the 1882-1883 school year, Atwater took a leave of absence from Wesleyan to study the digestibility of lean fish with von Voit in Germany.

[8] Together, they found fish comparable to lean beef; during this time he became aware of how German scientists were studying nutrition and hoped to bring similar research to the United States upon his return.

[13] Atwater had even begun writing in USDA publications in support of adopting the European model of scientific laboratories in domestic experiment stations.

By 1885, Atwater and Johnson had begun advising Congress and President Grover Cleveland on the creation of experiment stations at the land-grant colleges created through the Morrill Act in 1862.

[8] Atwater made clear that the publication was meant to be a collection of scientific papers and not a platform for swapping farm tips.

[13] Once the Storrs station was created, Atwater and his colleagues had begun conducting and publishing studies on the chemical compositions of food.

[18][13] In 1891, he resigned as director of the Office of Experiment Stations in order to return to the Storrs and focus exclusively on nutrition research.

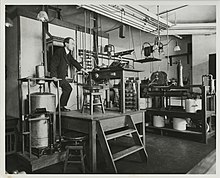

[16] Atwater went on to work with Physicist Edward Bennett Rosa and Nutritionist Francis Gano Benedict to design the first direct calorimeter large enough to accommodate human subjects for a period of days.

[20] The calorimeter measured human metabolism by analyzing the heat produced by a person performing certain physical activities; in 1896 they began the first of what would accumulate into close to 500 experiments.

[20] Through the calorimetry studies, greater awareness was brought to the food calorie as a unit of measure both for consumption and metabolism.

[8] His collaborator and successor, Frances Benedict continued his work and helped establish a Nutrition Laboratory in Boston with funding from the Carnegie Corporation.

Benedict studied the varying metabolism rates of infants born in two hospitals in Massachusetts, athletes, students, vegetarians, Mayans living in the Yucatán, and normal adults.

In 1919, Francis Benedict published a metabolic standards report with extensive tables based on age, sex, height, and weight.

[8] Both he and Johnson are considered responsible for focusing the role of the experiment stations on scientific study in service of the public and the tables and formulas Atwater created through his research are still in use today.

[8][25] His granddaughter, Catherine Merriam Atwater, the daughter of his son, Charles, was an author whom married economist John Kenneth Galbraith.