Calorimeter

A simple calorimeter just consists of a thermometer attached to a metal container full of water suspended above a combustion chamber.

Multiplying the temperature change by the mass and specific heat capacities of the substances gives a value for the energy given off or absorbed during the reaction.

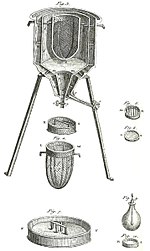

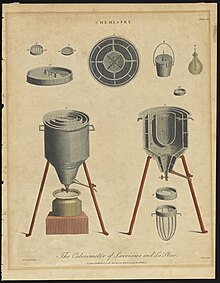

In 1761 Joseph Black introduced the idea of latent heat which led to the creation of the first ice calorimeters.

[1] In 1780, Antoine Lavoisier used the heat released by the respiration of a guinea pig to melt snow surrounding his apparatus, showing that respiratory gas exchange is a form of combustion, similar to the burning of a candle.

A mathematical correction factor, known as the phi-factor, can be used to adjust the calorimetric result to account for these heat losses.

The energy supplied to this heater can be varied as reactions require and the calorimetry signal is purely derived from this electrical power.

Constant flux calorimetry (or COFLUX as it is often termed) is derived from heat balance calorimetry and uses specialized control mechanisms to maintain a constant heat flow (or flux) across the vessel wall.

In more recent calorimeter designs, the whole bomb, pressurized with excess pure oxygen (typically at 30 standard atmospheres (3,000 kPa)) and containing a weighed mass of a sample (typically 1–1.5 g) and a small fixed amount of water (to saturate the internal atmosphere, thus ensuring that all water produced is liquid, and removing the need to include enthalpy of vaporization in calculations), is submerged under a known volume of water (ca.

The bomb, with the known mass of the sample and oxygen, form a closed system — no gases escape during the reaction.

A small correction is made to account for the electrical energy input, the burning fuse, and acid production (by titration of the residual liquid).

By using stainless steel for the bomb, the reaction will occur with no volume change observed.

A small factor contributes to the correction of the total heat of combustion is the fuse wire.

of the bomb is known, the heat of combustion of the flammable compound (CFC), of the wire (CW) and the masses (mFC and mW), and the temperature change (ΔT), the heat of combustion of the less flammable compound (CLFC) can be calculated with: The detection is based on a three-dimensional fluxmeter sensor.

The corresponding thermopile of high thermal conductivity surrounds the experimental space within the calorimetric block.

This is verified by the calculation of the efficiency ratio that indicates that an average value of 94% ± 1% of heat is transmitted through the sensor on the full range of temperature of the Calvet-type calorimeter.

In this setup, the sensitivity of the calorimeter is not affected by the crucible, the type of purgegas, or the flow rate.

[8] Sometimes referred to as constant-pressure calorimeters, adiabatic calorimeters measure the change in enthalpy of a reaction occurring in solution during which the no heat exchange with the surroundings is allowed (adiabatic) and the atmospheric pressure remains constant.

An example is a coffee-cup calorimeter, which is constructed from two nested Styrofoam cups, providing insulation from the surroundings, and a lid with two holes, allowing insertion of a thermometer and a stirring rod.

The inner cup holds a known amount of a solvent, usually water, that absorbs the heat from the reaction.

Adiabatic calorimeters most commonly used in materials science research to study reactions that occur at a constant pressure and volume.

They are particularly useful for determining the heat capacity of substances, measuring the enthalpy changes of chemical reactions, and studying the thermodynamic properties of materials.

A modulated temperature differential scanning calorimeter (MTDSC) is a type of DSC in which a small oscillation is imposed upon the otherwise linear heating rate.

In this mode the sample will be housed in a non-reactive crucible (often gold, or gold-plated steel), and which will be able to withstand pressure (typically up to 100 bar).

However, due to a combination of relatively poor sensitivity, slower than normal scan rates (typically 2–3 °C per min) due to much heavier crucible, and unknown activation energy, it is necessary to deduct about 75–100 °C from the initial start of the observed exotherm to suggest a maximum temperature for the material.

A much more accurate data set can be obtained from an adiabatic calorimeter, but such a test may take 2–3 days from ambient at a rate of 3 °C increment per half hour.

This permits determination of the midpoint (stoichiometry) (N) of a reaction as well as its enthalpy (delta H), entropy (delta S) and of primary concern the binding affinity (Ka) The technique is gaining in importance particularly in the field of biochemistry, because it facilitates determination of substrate binding to enzymes.

In traditional heat flow calorimeters, one reactant is added continuously in small amounts, similar to a semi-batch process, in order to obtain a complete conversion of the reaction.

In contrast to the tubular reactor, this leads to longer residence times, different substance concentrations and flatter temperature profiles.

This can lead to the formation of by-products or consecutive products which alter the measured heat of reaction, since other bonds are formed.

By analyzing the heat content of the steam, engineers can ensure that the resource meets the required specifications for efficient energy production.