Wildcat

[4] The European wildcat evolved during the Cromerian Stage about 866,000 to 478,000 years ago; its direct ancestor was Felis lunensis.

[6] The wildcat is categorized as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List since 2002, since it is widely distributed in a stable global population exceeding 20,000 mature individuals.

Some local populations are threatened by introgressive hybridisation with the domestic cat (F. catus), contagious disease, vehicle collisions and persecution.

[11] Felis lybica was the name proposed in 1780 by Georg Forster, who described an African wildcat from Gafsa on the Barbary Coast.

[12] In subsequent decades, several naturalists and explorers described 40 wildcat specimens collected in European, African and Asian range countries.

In the 1940s, the taxonomist Reginald Innes Pocock reviewed the collection of wildcat skins and skulls in the Natural History Museum, London, and designated seven F. silvestris subspecies from Europe to Asia Minor, and 25 F. lybica subspecies from Africa, and West to Central Asia.

[19] The European wildcat's direct ancestor was Felis lunensis, which lived in Europe in the late Pliocene and Villafranchian periods.

Fossil remains indicate that the transition from lunensis to silvestris was completed by the Holstein interglacial about 340,000 to 325,000 years ago.

The species size varies according to Bergmann's rule, with the largest specimens occurring in cool, northern areas of Europe and Asia such as Mongolia, Manchuria and Siberia.

Male wildcats have pre-anal pockets on the tail, activated upon reaching sexual maturity, play a significant role in reproduction and territorial marking.

[25] The European wildcat inhabits temperate broadleaf and mixed forests in Europe, Turkey and the Caucasus.

Between the late 17th and mid 20th centuries, its European range became fragmented due to large-scale hunting and regional extirpation.

[27] It occurs around the Arabian Peninsula's periphery to the Caspian Sea, encompassing Mesopotamia, Israel and Palestine region.

The size of home ranges of females and males varies according to terrain, the availability of food, habitat quality and the age structure of the population.

Females tend to be more sedentary than males, as they require an exclusive hunting area when raising kittens.

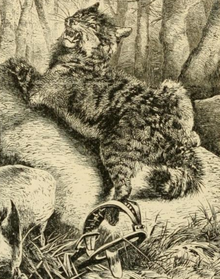

When attacking large prey, it leaps upon the animal's back, and attempts to bite the neck or carotid.

[33] It also preys on dormice, hares, nutria (Myocastor coypus) and birds, especially ducks and other waterfowl, galliformes, pigeons and passerines.

[36] The African wildcat preys foremost on murids, to a lesser extent also on birds, small reptiles and invertebrates.

[41] Because of its habit of living in areas with rocks and tall trees for refuge, dense thickets and abandoned burrows, wildcats have few natural predators.

Competitors include the golden jackal (Canis aureus), red fox, marten, and other predators.

In Tajikistan, the grey wolf (Canis lupus) is the most serious competitor, having been observed to destroy cat burrows.

[44] Seton Gordon recorded an instance where a wildcat fought a golden eagle, resulting in the deaths of both combatants.

[1] The wildcat population in Scotland has declined since the turn of the 20th century due to habitat loss and persecution by landowners.

[48] In the former Soviet Union, wildcats were caught accidentally in traps set for European pine marten.

One method of catching wildcats consists of using a modified muskrat trap with a spring placed in a concealed pit.

[51][52] An African wildcat skeleton excavated in a 9,500-year-old Neolithic grave in Cyprus is the earliest known indication for a close relationship between a human and a possibly tamed cat.

[53] Results of genetics and morphological research corroborated that the African wildcat is the ancestor of the domestic cat.