Wilhelm Busch

He described himself in autobiographical sketches and letters as sensitive and timid, someone who "carefully studied fear",[11] and who reacted with fascination, compassion, and distress when animals were killed in the autumn.

[14] In the autumn of 1841, after the birth of his brother Otto, Busch's education was entrusted to the 35-year-old clergyman, Georg Kleine, his maternal uncle at Ebergötzen, where 100 children were taught within a space of 66 m2 (710 sq ft).

[31] Busch's parents had his tuition fees paid for one year, so in May 1852 he traveled to Antwerp to continue study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts under Josephus Laurentius Dyckmans.

[35] Busch was ravaged by disease, and for five months spent time painting and collecting folk tales, legends, songs, ballads, rhymes, and fragments of regional superstitions.

[41] Kaspar Braun, who published the satirical newspapers, Münchener Bilderbogen (Picture Sheets from Munich) and Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), proposed a collaboration with Busch.

[73] In German, Eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen, Max and Moritz is a series of seven illustrated stories concerning the mischievous antics of two boys, who are eventually ground up and fed to ducks.

[74] The publisher's works were heavily scrutinized or censored,[75] and the state's attorney in Offenburg charged Schauenberg with "vilification of religion and offending public decency through indecent writings" – a decision which affected Busch.

Helen Who Couldn't Help It, which was soon translated into other European languages, satirizes religious hypocrisy and dubious morality:[79][80] Ein guter Mensch gibt gerne acht, Ob auch der andre was Böses macht; Und strebt durch häufige Belehrung Nach seiner Beß'rung und Bekehrung A saintly person likes to labor For the correction of his neighbor, And sees, through frequent admonition, To his improvement through contrition.

Johanna Kessler was married to a much older man and entrusted her children to governesses and tutors, while she played an active role in the social life of Frankfurt.

The character of Mr. Schmock – the name based on the Yiddish insult "schmuck" – shows similarities with Johanna Kessler's husband, who was uninterested in art and culture.

Busch biographer Michaela Diers declares the story "tasteless work, drawing on anti-French emotions and mocking the misery of French people in Paris, which is occupied by Prussian troops".

[91] Without pathos, Busch makes Knopp become aware of his mortality:[92] Rosen, Tanten, Basen, Nelken Sind genötigt zu verwelken; Ach — und endlich auch durch mich Macht man einen dicken Strich.

The following marriage proposal is, according to Busch biographer Joseph Kraus, one of the shortest in the history of German literature:[93][94] "Mädchen", spricht er, "sag mir ob..." Und sie lächelt: "Ja, Herr Knopp!"

[98] Clement Dove ridicules the bourgeois amateur poet circle of Munich, "The Crocodiles" (Die Krokodile), and their prominent members Emanuel Geibel, Paul von Heyse, and Adolf Wilbrandt.

[101] Eva Weissweiler saw in the play Busch's attempt to prove himself in the novella genre, believing that everything that angered or insulted him, and his accompanying emotional depths, are apparent in the story.

[102] The 1895 story The Butterfly (Der Schmetterling) parodies themes and motifs and ridicules the religious optimism of a German romanticism that contradicted Busch's realistic anthropology influenced by Schopenhauer and Charles Darwin.

[109] A strong influence on Busch was Adriaen Brouwer, whose themes were farming and inn life, rustic dances, card players, smokers, drunkards, and rowdies.

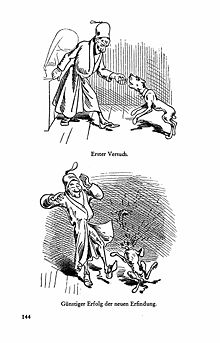

[115] The early stories follow the pattern of children's books of orthodox education, such as those by Heinrich Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter, that aim to teach the devastating consequences of bad behaviour.

This letterpress printing technique was developed by English graphic artist Thomas Bewick near the end of the eighteenth century and became the most widely used reproduction system for illustrations over the years.

[126] The contrast in his later work between comic illustration and its seemingly serious accompanying text – already demonstrated in his earlier Max and Moritz – is shown in Widow Bolte's mawkish dignity, which is disproportionate to the loss of her chickens:[127] Fließet aus dem Aug', ihr Tränen!

[128] Many of his picture stories use verses with trochee structure:[129] Master Lampel's gentle powers Failed with rascals such as ours The overweighting of the stressed syllables strengthens the humour of the lines.

Sharp pencils pierced through models, housewives fall onto kitchen knives, thieves are spiked by umbrellas, tailors cut their tormentors with scissors, rascals are ground in corn mills, drunkards burn, and cats, dogs, and monkeys defecate while being tormented.

[135] Caning, a common aspect of nineteenth-century teaching, is prevalent in many of his works, for example Meister Druff in Adventures of a Bachelor and Lehrer Bokelmann in Plish and Plum, where it is shown as an almost sexual pleasure in applying punishment.

His uncle Kleine beat him once, not with the conventional rattan stick, but symbolically with dried dahlia stalks, this for stuffing cow hairs into a village idiot's pipe.

The painter Eduard Daelen, also a writer, echoed Busch's anti-Catholic bias, putting him on equal footing with Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and uncritically quoting correspondences.

[151] After reading this biography Johannes Proelß posted an essay in the Frankfurter Zeitung, which contained many biographical falsehoods – as a response to this, Busch wrote two articles in the same newspaper.

The last such essay was published under the title, From Me About Me (Von mir über mich), which includes fewer biographical details and less reflection on bitterness and amusement than Regarding Myself.

Satirizing the self-publicizing artist's attitude and his overblown adoration, it varies from Busch's other stories as each scene does not contain prose, but is defined with music terminology, such as "Introduzione", "Maestoso", and "Fortissimo vivacissimo".

[172] Busch's greatest success, both within Germany and internationally, was with Max and Moritz:[173] Up to the time of his death it was translated into English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish, and Walloonian.

[180] In 1958 the Christian Democratic Union used the Max and Moritz characters for a campaign in North Rhine-Westphalia, the same year that the East German satirical magazine Eulenspiegel used them to caricature black labour.