William Blackstone

After switching to and completing a Bachelor of Civil Law degree, he was made a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, on 2 November 1743, admitted to Middle Temple, and called to the Bar there in 1746.

These were massively successful, earning him a total of £453 (£89,000 in 2023 terms), and led to the publication of An Analysis of the Laws of England in 1756, which repeatedly sold out and was used to preface his later works.

With his growing fame, he successfully returned to the bar and maintained a good practice, also securing election as Tory Member of Parliament for the rotten borough of Hindon on 30 March 1761.

In November 1765 he published the first of four volumes of Commentaries on the Laws of England, considered his magnum opus; the completed work earned Blackstone £14,000 (£2,459,000 in 2023 terms).

[19] On 20 November 1741 he was admitted to the Middle Temple,[20] the first step on the road to becoming a barrister, but this imposed no obligations and simply allowed a legal career to be an option.

[22] In addition to his formal studies, Blackstone published a collection of poetry which included the draft version of The Lawyer to his Muse, his most famous literary work.

[26] His call to the Bar saw Blackstone begin to alternate between Oxford and London, occupying chambers in Pump Court but living at All Souls College.

Records show a "perfectionist zeal" in organising the estates and finances of All Souls, and Blackstone was noted for massively simplifying the complex accounting system used by the college.

[34] In 1750 Blackstone completed his first legal tract, An Essay on Collateral Consanguinity, which dealt with those claiming a familial tie to the founder or All Souls in an attempt to gain preeminence in elections.

[35] Completion of his Doctor of Civil Law degree, which he was awarded in April 1750, admitted him to Convocation, the governing body of Oxford, which elected the two burgesses who represented it in the House of Commons, along with most of the university officers.

[46] He also wrote a manual on the Court's practice, and through his position gained a large number of contacts and connections, as well as visibility, which aided his legal career significantly.

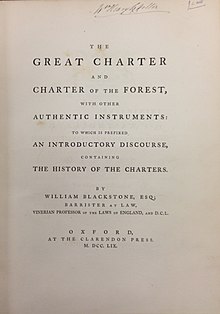

Published by the Clarendon Press, the treatise was intended to demonstrate the "Order, and principal Divisions" of his lecture series, and a structured introduction to English law.

[51] Because of the success of the Commentaries, Prest remarks that "relatively little scholarly attention has been paid to this work";[49] at the time, however, it was hailed as "an elegant performance ... calculated to facilitate this branch of knowledge".

The lecture was tremendously popular, being described as a "sensible, spirited and manly exhortation to the study of the law"; the initial print run sold out, necessitating the publication of another 1,000 copies, and it was used to preface later versions of the Analysis and the first volume of the Commentaries.

[56] This suit, along with the struggle over the Vinerian Professorship and other controversies, damaged his reputation within the university, as evidenced by his failure to win election as Vice Warden in April 1759, losing to John White.

[58] Prest attributes Blackstone's unpopularity to specific personality traits, saying his "determination...in pursuit of causes to which he committed himself could irritate as well as intimidate those of a more relaxed disposition.

On the death of the third Earl of Abingdon, Blackstone was retained as counsel for the executors and trustees to oversee the family's attempts to pay off debts and meet other obligations.

[65] The Blackstones had a large estate in Wallingford in Berkshire, including 120 acres (46 ha) of pastureland around the River Thames and the right of advowson over St Peter's Church.

His chosen career did lend him to politics, in that the lawyers in the House of Commons were often added to select committees to provide them with technical expertise in drafting legislation.

Owen Ruffhead described Volume I as "masterly", noting that "Mr Blackstone is perhaps the first who has treated the body of the law in a liberal, elegant and constitutional manner.

Neighbours included the Sardinian ambassador, Sir Walter Rawlinson, Lord Northington, John Morton and the Third Earl of Abingdon, making it an appropriate house for a "great and able Lawyer".

[88] After only four days it was announced that Joseph Yates was to move to the Common Pleas, and Blackstone was again sworn in as a judge, this time of the Court of King's Bench.

[90] Prest describes him as an "exceptionally careful, conscientious and well-respected judge ... his judgments ranging between narrowly framed technicalities [and] broad statements of public commentary".

This played to his strengths, and many of his decisions are considered farsighted; the principle in Blaney v Hendricks, for example, that interest is due on an account where money was lent, which anticipated Section 3 of the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1934.

[97] Blackstone had long suffered from gout, and by November 1779 also had a nervous disorder which caused dizziness, high blood pressure, and possibly diabetes.

His brother-in-law, James Clitherow, also published in 1781[101] two volumes of his law reports which added £1,287 to the estate, and in 1782 the Biographical History of Sir William Blackstone appeared.

[108] The US academic Robert Ferguson notes that "all our formative documents – the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers and the seminal decisions of the Supreme Court under John Marshall – were drafted by attorneys steeped in Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England.

The bronze statue is a nine-foot (2.7 m) standing portrait of Blackstone wearing judicial robes and a long curly wig, holding a copy of Commentaries.

[115] The North Wall Frieze in the courtroom of the Supreme Court of the United States depicts William Blackstone, as one of the most influential legal commentators in world history.

[116] Among the most well-known of Blackstone's contributions to judicial theory is his own statement of the principle that it "is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.