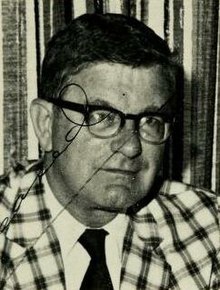

William D. Mullins

William David Mullins (August 13, 1931 – March 2, 1986) was an American politician, educator, and professional baseball player who served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives from 1977 until his death in 1986.

After graduating from Providence College in 1953, Mullins signed with the Washington Senators as a pitcher, playing in their minor league farm system.

Despite his credentials as a "hard-nosed fiscal conservative", Mullins used his position in the legislature to advocate for local aid to many of the small cities and towns outside the Boston area.

[4][5] After graduating high school in 1949, Mullins attended Providence College, having received an athletic scholarship to play on the baseball team.

[7] In a 1953 game against a dominant University of Connecticut team, Mullins gave up just five hits while netting eight strikeouts; the Hartford Courant reported that he had a "dazzling curveball".

Originally run out of a rented room at a social center, by 1982 the institute had grown to occupy an elementary school building, had an enrollment of 30 students from across Massachusetts, and maintained a staff of professional speech-language pathologists.

[3] During his tenure as selectman, Mullins led the creation of a zoning law which prevented abortion clinics from operating in Ludlow, and oversaw a proposal which would have seen the construction of a $100 million oil power plant in the town.

[39] Chmura filed a legal petition to overturn the result, alleging that electoral irregularities in the Palmer precinct affected the outcome of the election.

[47] In the general election, Mullins faced independent candidate Lucille G. Ouimette, the president of the Chicopee board of aldermen.

[53] In both the primary and the general election, Mullins was narrowly defeated in the Chicopee portion of the district, but won overwhelmingly in Ludlow.

However, Mullins largely ignored Trybulski's attacks and ran a positive campaign, focusing on $10 million of additional funds given to Chicopee during his tenure.

[66] In 1983, Mullins joined a group of Democratic legislators who sought to oust House Speaker Thomas W. McGee in favor of reformer George Keverian, the House majority leader; though both were Democrats, McGee had been seen as "squelching the rights of rank and file members", and drew ire for his support for special-interests.

[74][75] Among those in attendance were Governor Michael Dukakis; U.S. Representative Edward Boland; three busloads of state legislators; and Raymond Flynn and Richard Neal, the mayors of Boston and Springfield.

[80][81] In 1977, Mullins led a group of hardline representatives to successfully pass a bill which prohibited the use of state funds for abortions in all cases.

"[82] When a budget compromise containing a provision banning the public funding of abortions except in cases of rape and incest passed in the House the following year, Mullins declared it to be a "Pyrrhic victory".

[81] In 1978, Mullins sponsored a controversial bill which would have increased the penalty for taking a girl out of the state to receive an abortion without parental consent to a maximum of five years in prison and a $2,000 fine.

As a result of his efforts during his first term in office, the Massachusetts Citizens for Life organization named Mullins the Pro-Life Legislator of the Year.

[88] He criticized the state for the amount of resources it gave to Boston, particularly the proposed bailout of the "financially crippled" Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

Mullins also stated that due to Boston's reputation as "the car-theft capital of the world", drivers in Western Massachusetts were being forced to pay higher auto insurance rates.

[88] Though described as a "hard-nosed fiscal conservative", Mullins was a strong proponent of home rule and was considered to be an "expert on local aid".

Mullins called the proposition "a joke", and stated its passage hurt local communities, who were being forced to cut essential programs, including trash and ambulance services.

[50][94] In 1981, Mullins filed a bill which would have required the state to give all the money it collected from the sales tax, around $350 million, to towns and cities in the form of local aid as a workaround to Proposition 2½.

[112][113] Mullins "ardently" supported the reinstatement of the death penalty, stating: "At some point, we have to stop worrying about those who murder and maim and be concerned about the victims and their families".

[114] Additionally, Mullins voted in favor of a bill which would prevent minors and people convicted of felonies or drug charges from owning guns.

In response, Mullins called the board "weak", and sponsored a successful bill requiring utility companies to notify communities before conducting sprays.

Mullins argued that the university lacked an indoor facility capable of holding its 24,000 students and that the arena would help "expand the athletic program" at UMass.

[123][124] After his death the following year, Keverian and Massachusetts Senate president William Bulger introduced legislation which would set aside state funds in order to build the arena, which was to be named after Mullins.

[127] Additionally, despite his initial support, Bulger stalled the bill in the Senate for three years, using it to gain leverage over Keverian on other legislation.

[129][130] Construction on the $50 million facility began in early 1991, and the 10,000-seat William D. Mullins Memorial Center formally opened in February 1993.

Mullins stated that "every time I'd pick up a cigarette, my teenage son and daughter would grab their throats", and that he quit smoking due to Kitty Dukakis's public struggle with addiction.