William F. Wells

By adding fresh seawater each day, and then using the clarifier to concentrate the larvae, Wells was able to resupply their food without losing them.

Wells also cultivated the oyster Crassostrea virginica, the mussel Mytilus edulis, the clams Mya arenaria and Spisula solidissima, and the scallop Argopecten irradians.

German bacteriologist Carl Flügge in 1899 was the first to show that microorganisms in droplets expelled from the respiratory tract are a means of disease transmission.

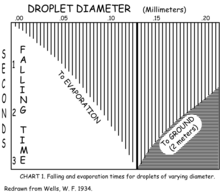

[8][9] Wells' major contribution was to show that the nuclei of evaporated droplets can remain in the air for long enough for others to breathe them in and become infected.

[10] He and his wife developed the Wells curve, which describes how the size of respiratory droplets influences their fate and thus their ability to transmit disease.

[3][11] With Richard L. Riley, he also developed the Wells-Riley equation "to express the mass balance of transmission factors under steady state conditions.

In 1935, Wells helped develop UVGI barriers for the Infants' and Children's Hospital in Boston, using cubicle-like rooms subjected to high-intensity UV light to reduce cross-contamination.

At the VA Hospital in Baltimore, collaborating with Riley, John Barnwell, and Cretyl C. Mills, he built a chamber for 150 guinea pigs to be exposed to air from infectious patients in a nearby TB ward.

Although this was exactly the rate Wells had predicted, skeptics complained that other methods of transmission (such as the animals' food and water) had not been conclusively ruled out.

A second long-term study was begun, this time with a second chamber for an additional 150 guinea pigs, whose air was sterilized with UVGI.