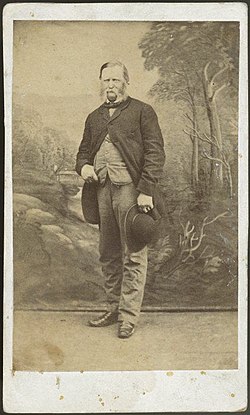

William Fox (politician)

Fox was born on 20 January 1812 at 5 Westoe Village in South Shields, then part of County Durham,[1] in north-east England, and baptised on 2 September of that year;[2] he was the son of the Rev.

Upon his arrival in Wellington Fox's legal qualifications were recognised, but there was little work, and so he supplemented his income by writing for local periodicals.

That year, following the death of Arthur Wakefield, Fox was appointed local agent for the New Zealand Company at Nelson.

He also condemned the colonial government's "weak" response to the killing of Arthur Wakefield, a New Zealand Company official who had attempted to expand the settlement at Nelson into Māori-held lands.

Poor planning and inaccurate land surveying had left colonists with considerably less than had been promised them, and Fox was responsible for resolving the matter.

He accomplished this mainly because of the short distance between Nelson and Wellington, which enabled him to win the position before instructions could be received from other cities.

He was not the first choice of the Company's board in London, which preferred Dillon Bell, but his quick action managed to gain him enough support to receive the appointment.

He was a strong opponent of Governor George Grey, had suspended the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846 to grant self-government to the settlers.

He discussed his ideas about a constitution for New Zealand, strongly supporting self-rule, provincial autonomy, and two elected houses of parliament.

When the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 was passed by Britain's parliament the following year, it incorporated some of Fox's ideas but was not satisfactory to him.

[5] Before returning to New Zealand, Fox and his wife spent some time travelling in Canada, the United States, and Cuba.

He fought on a strong platform of provincial autonomy, and was particularly opposed to the government formed the following year by Henry Sewell, who took the newly created office of Premier of New Zealand.

Fox appears to have changed his views somewhat regarding Māori land rights, as he strongly opposed the government's policy on that issue.

He blamed Stafford's administration, along with Governor Thomas Gore Browne, for the wars in Taranaki, which broke out when a Māori chief refused to sell his land.

Fox was widely believed to have converted to support of the Māori, although many modern historians claim that his opposition to land seizure was due to a pragmatic wish to avoid war, not a change of philosophy.

[6] After becoming increasingly involved in a dispute with Grey over responsibility for policy towards Māori, Fox lost a vote of confidence in 1862.

Fox was elected to parliament, and relaunched his attack on Stafford's policies on Māori relations and provincial affairs.

His role in politics, however, was not quite over – when George Waterhouse, Stafford's successor, suddenly resigned, Fox was called upon to assume the premiership as a caretaker until a new leader was found.

One boy was killed, and the other, Ngatau Omahuru, was given by Māori scout, Pirimona, to Herewini of the Ngāti Te Ūpokoiri Iwi.

While in Whanganui the boy came to the attention of the magistrate Walter Buller, who purchased him a set of European clothes and boots.

At 16, William junior joined a law firm as a clerk with Buller, Lewis and Gully, where he received about five years training.

Later after the closure of Parihaka he worked as a translator and interpreter in Whanganui and then set up a business in Hawera teaching the Māori language.

[9] He continued to undertake considerable physical exercise and, guided by Harry Peters, climbed Mount Taranaki in 1892, aged 80.